‘Sometimes superman would like to be Clark Kent, just a normal person with normal responsibilities’ —Christopher Reeve in The Making of Superman the Movie by David Michael Petrou (Warner Books, 1978)

1. Darvin

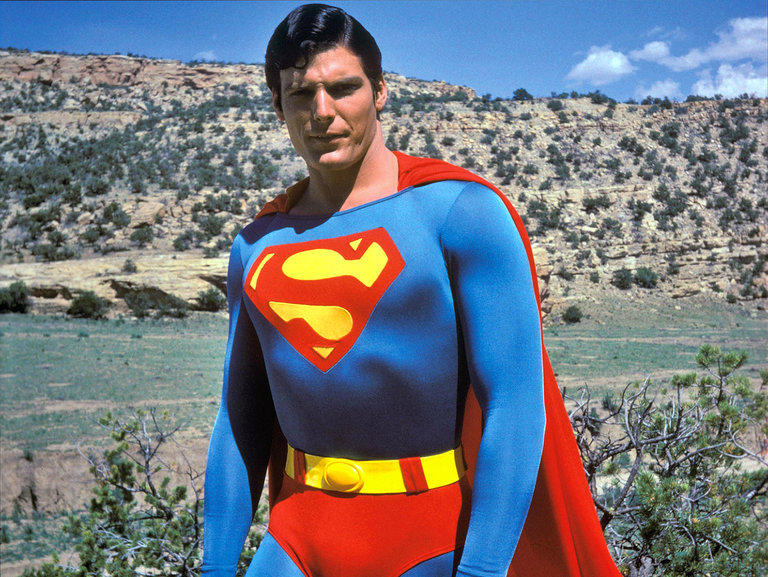

The catalogue for the “Icons and Idols: Hollywood” auction, held at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills, California, on 16 December 2019, boasted several notable items for sale. Lot 149: a felt hat made by Lock & Co Hatters of London and worn by Charlie Chaplin in his 1947 film, Monsieur Verdoux. Lot 355: a white T-shirt emblazoned with a Nike Swoosh, dirtied with “studio soiling” and worn by Tom Hanks in 1994’s Forrest Gump, visible in a sequence when Gump spends three years running across America. Lot 298: a 1968 Husqvarna Viking 360 motorcycle once purchased by the actor Steve McQueen. Lot 358: a “pipe-weed” pipe, used by Sir Ian Holm as Bilbo Baggins in 2001’s The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. But there was one item that was set to be the centrepiece of the event, and to which two double-page spreads of the glossy catalogue were devoted. Lot 385: a blood-red cape, emblazoned on the back with a stylised “S” picked out in blue stitching. It had been worn in Superman: The Movie by Christopher Reeve, a handsome, athletic and relatively unknown actor who had just turned 26 when the film came out in 1978 and would become forever associated with the superhero he played — the “Man of Steel” with his unmatchable strength, speed and moral fibre — and also his alter-ego, the bumbling, bespectacled reporter, Clark Kent.

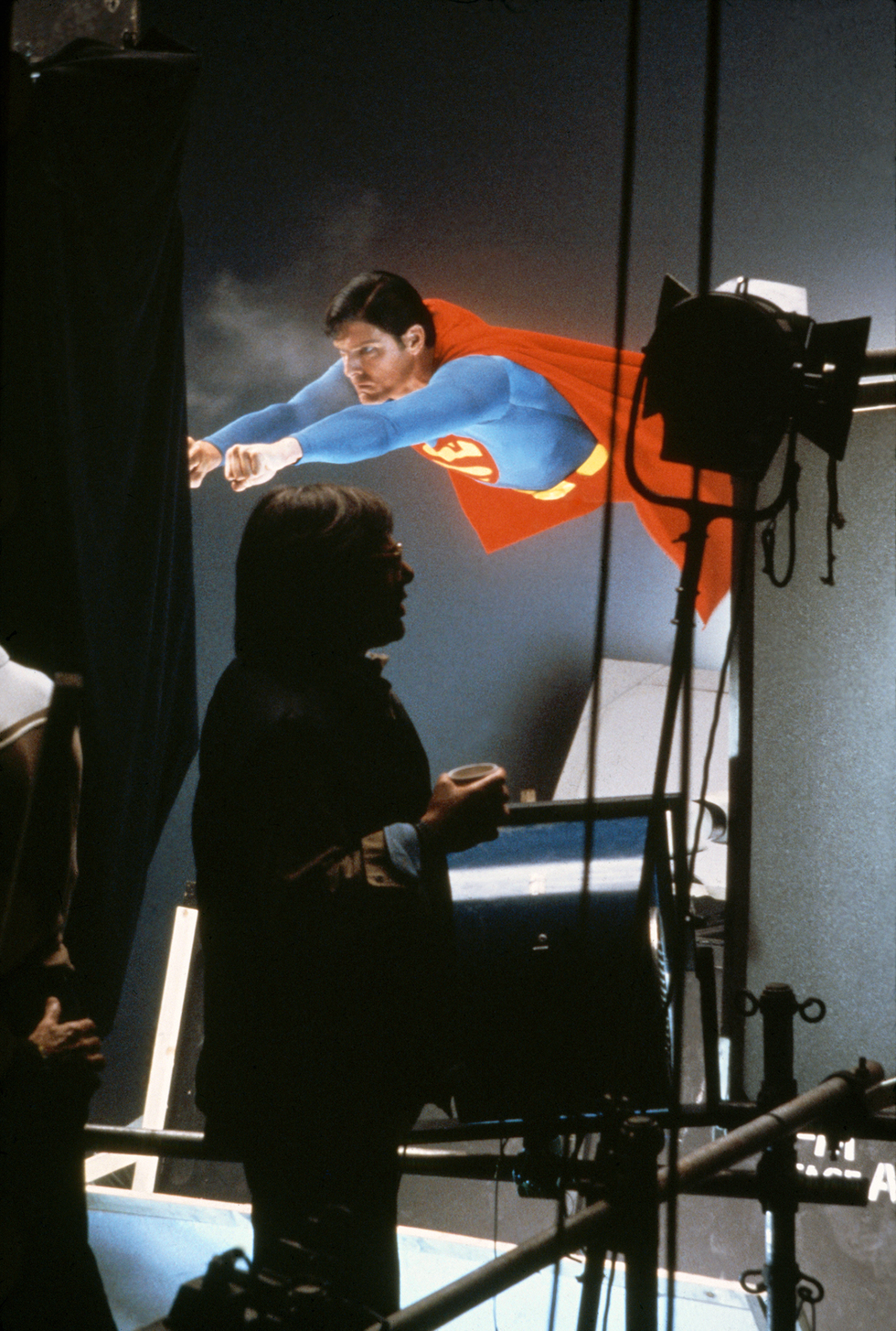

The cape was a remnant of the outfit created by costume designer Yvonne Blake for the film, adapted from the drawings of Joe Shuster, who invented Superman in the Thirties with his high-school friend Jerry Siegel. Boots, tights, cape and torso-hugging shirt with an “S” on the chest. Also, overshorts: although according to David Michael Petrou’s 1978 book, The Making of Superman the Movie, when Reeve wore them, Blake had to insert a “large swimmer’s cup” as “some obvious protuberances” were creating continuity problems as they were “not always in exactly the same place”.

Because of the cape’s dimensions, it was understood to be a “walking” cape; as opposed to the “flying” capes, which were wider and had slits cut into them through which the harnesses that would make Reeve appear to take to the skies could be attached. It was thought to be one of six, as suggested by a note, handwritten close to the hem, which read: “(was turned up) No 5/6 relined 1/3/78”. The cape appeared to be made from some type of cotton, and was still bright, with little evidence of fraying, unlike costumes made from synthetic fabrics which, while looking more futuristic, often proved quicker to degrade.

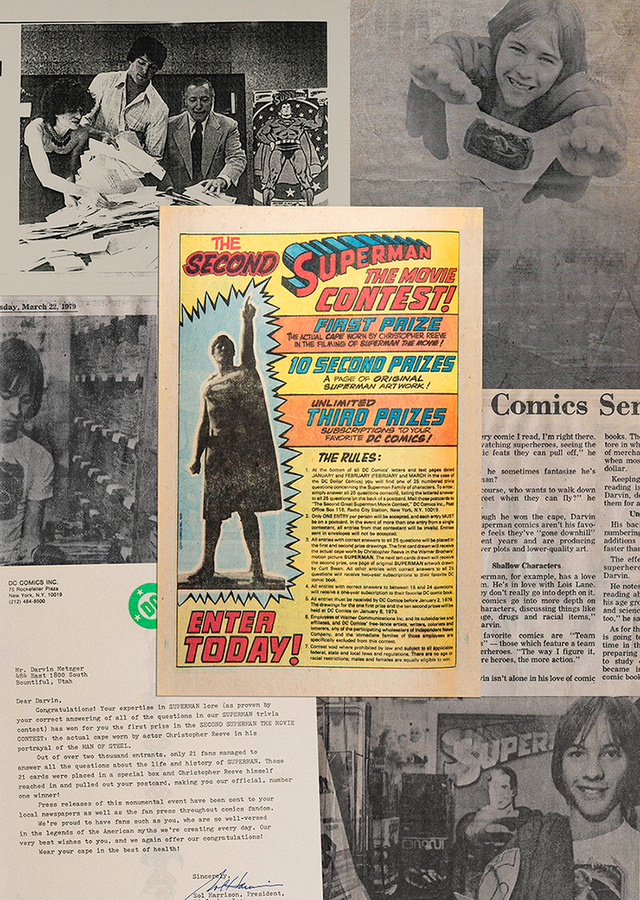

But it was not the condition that made the cape such an important item. Included in the lot was a letter, written in 1979 by the editor and publisher of DC Comics, Jack C Harris, to a teenage boy in Utah. “Dear Darvin,” it began. “Congratulations! Your expertise in SUPERMAN lore… has won you first prize in the SECOND SUPERMAN THE MOVIE CONTEST, the actual cape worn by actor Christopher Reeve.”

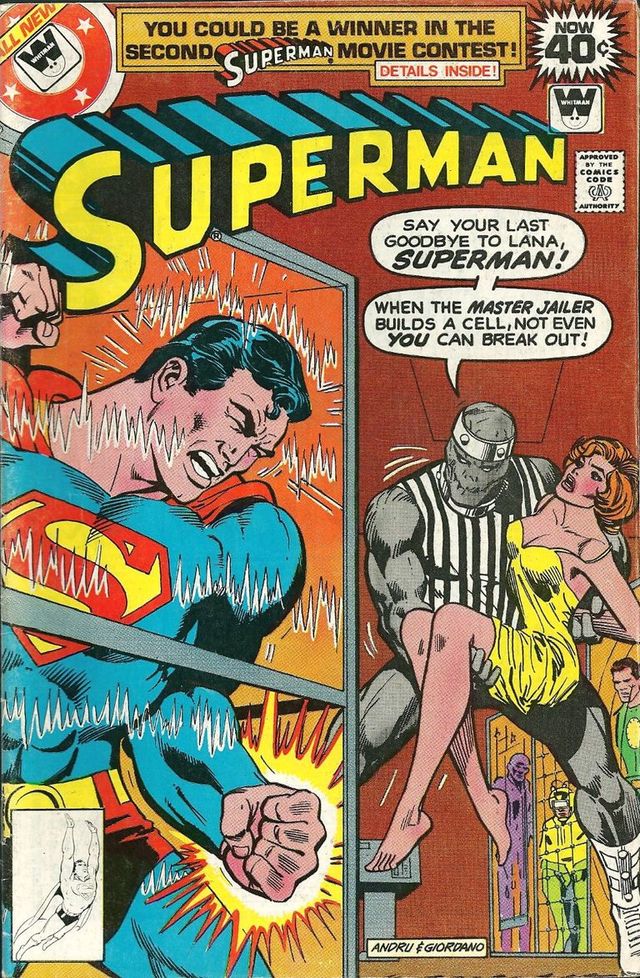

The letter confirmed the results of a competition promoted in issue #331 of Superman, a copy of which was included in the auction lot. The rules had been deceptively simple: correctly answer 25 trivia questions about the world of Superman and send them, on a postcard, to DC Comics in New York. But, reported Harris in his letter, the questions were so difficult that only 21 contestants managed to get them all correct, and, as luck would have it, Christopher Reeve was in town when they needed to pick a winner. It was he who had selected Darvin’s card. “We’re proud to have fans such as you,” Harris concluded, “who are so well-versed in the legends of the American myths we’re creating every day. Our very best wishes to you, and again we offer our congratulations! Wear your cape in the best of health!”

Darvin Metzger grew up in Bountiful, Utah, a town, like many others in the area, with a predominantly Mormon population (and also the town from which, in 1974, Ted Bundy abducted his twelfth murder victim, 17-year-old Debra Kent). Darvin and his family were not Mormons and he felt somewhat isolated as a child, until he discovered comic books. It gave him a thing of his own and, after he started working in a comic book store as a teenager, several of his customers, other young men who shared his interests, became his friends.

Superman was never his favourite. He leaned more towards Spider-Man or Batman: characters who were more realistic, in relative terms at least. A teenager who acquires powers, and a human who invents incredible things to fight crime. With Superman there was too much power involved — the same thing that put him off Hulk or Thor — the so-called “Man of Tomorrow” didn’t have to use his brains to solve problems, or at least so it seemed to Darvin at the time.

When they saw the announcement of the cape competition in Superman #331, Darvin and his friends decided to give it a shot. Here was something in which they were specialists; they actually stood a chance. They pooled their knowledge and took advantage of the archive of Superman books at Cosmic Aeroplane Bookstore in Salt Lake City, where Darvin, now 17 years old, was working. The questions were undeniably hard: what colour is super-villain Lex Luthor’s hair? But he was bald! Until one boy remembered an early appearance of Superman’s nemesis in which — eureka! — he was depicted with red hair. Despite the rules stipulating against it, the boys entered multiple entries under fake names to increase their chances of winning.

Darvin was working at the comic book store when he received a call from his father telling him to come home right away. Assuming there was an emergency, he jumped in his car and drove the 20 or so miles to Bountiful. When he found no obvious cause for the summons he got upset with his dad, but just then the phone rang. “It’s for you,” his father said. It was a representative of DC Comics, telling Darvin his name had been drawn and he had won first prize: the Superman cape.

It felt great to have won, and Darvin was excited, though a small part of him felt sad that he hadn’t won DC Comic’s first Superman: The Movie competition, for which the prize was a part in the film itself (the two winners appeared as members of Clark Kent’s high-school football team). Also, the strategy that he and his friends had devised had worked: of the successful 21 entries, six others were from Salt Lake City; even Darvin’s dog, Duke, won a third-tier prize, a two-year subscription to a DC title of his choice, though Darvin was too sheepish to claim it. His story appeared in the Davis County Clipper, with a photograph of Darvin outside his house wearing the cape, smiling, arms raised, which the paper transposed over a picture of his street in Bountiful so that he appeared to be flying over the rooftops.

Because Darvin worked in the field, he understood the importance of what he had. He had already amassed a collection of 10,000 comics — often exchanging his wages at Cosmic Aeroplane for store credit — which he kept in his bedroom in Mylar bags. He stored the cape carefully at his parents’ house in Bountiful for the next few years while he worked somewhat aimless jobs, wondering what to do with his life, until, one day, he made a spur-of-the-moment decision: he would join the US Navy.

It was a change of heart that surprised not only Darvin but his father, with whom he had fought when the time had come for him, like all 18-year-old American males, to register for Selective Service. When Darvin had received his paperwork he had thrown it in the fire. Now he would be based at Moffett Federal Airfield in Northern California, and specialise in aviation electronics (“Statistically speaking, of course,” as Reeve’s Superman reminds Margot Kidder’s Lois Lane, whom he has just rescued from a helicopter teetering on the roof of a skyscraper, flying is “still the safest way to travel”).

By 1988, Darvin was in his late twenties and married, with a young son and baby daughter. He and his wife liked California, but soon the family’s finances started to feel stretched: Darvin’s wages did not go far enough, and they had never been the best at budgeting. He had sold his comic book collection in 1981, before he’d joined the military, to pay back a friend who’d lent him money for a truck; it was time to part with the cape too.

He gave it to an acquaintance who ran a comic book store, Dick Swan, to display behind the counter — it seemed a shame for him to keep it at home in a box — until Dick mentioned that he knew someone who might be interested in buying it. Darvin had some qualms: he well knew that the value of the cape might go up in years to come. But Christmas was approaching and he needed the money now. When Dick told him the buyer had offered $600, he took it.

The appeal of celebrity memorabilia is both hard to deny and, at times, to fathom. Clothes that musicians and movie stars have worn, gifts they have given and received, letters they have written, tissues they have blown their noses in — a Kleenex used by Scarlett Johansson during an appearance on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno was sold for charity in 2008 and raised £3,600 — are bought and sold like antiques and worshipped like relics. Today, a piece of toast with a bite mark from a pop star can get the attention once afforded to a crucifix touched by an apostle (the toast was bitten by One Direction’s Niall Horan and put on eBay by an Australian TV company in 2012, where it reportedly attracted a top bid of almost $(AU)$100,000, equivalent to £65,000). Such items, it seems, offer a chance to own a piece of collective pop history and be close to a star who seems out of reach, particularly if they have come to the end of their (ordinary, human) lifespan. It is a way to feel their residual energy, perhaps, or at least a few dead skin cells.

Celebrity memorabilia sales also make for easy news stories. In October last year, an acrylic and mohair cardigan worn by Nirvana singer Kurt Cobain during the band’s 1993 MTV Unplugged performance, complete with stains and cigarette burns, sold for $334,000 making it — in a possibly not terribly strong field — the most expensive item of knitwear ever bought at auction. In December 2019, reality star Kim Kardashian West spent $65,625 on a velvet jacket worn by Michael Jackson, and a further $56,250 on a white fedora he wore to perform his song “Smooth Criminal”: both Christmas presents, she announced on Instagram, for her six-year-old daughter, North. Another Instagram user mocked up a fake post purporting to be from Kardashian West, announcing that she had also purchased for North the bloodied white shirt in which President John F Kennedy was assassinated; at least one website reported the purchase as fact, until Kardashian West highlighted the error. (And perhaps it wasn’t even so far-fetched: at the time of writing, the website Moments in Time is selling, for $125,000, a “bullet dented” medallion that rapper Tupac Shakur was apparently wearing when he was shot and wounded in 1994.)

The market in movie memorabilia alone is estimated to have grown from an estimated £27m 10 years ago to between £155m and £310m today, and the overall global celebrity memorabilia market has been estimated at beyond a billion. There are numerous auction houses specialising in this area: Heritage Auctions in Houston, Profiles in History in Calabasas and Prop Store in the UK, to name just three, as well as Julien’s Auctions in Los Angeles, which sold the Michael Jackson jacket and hat and the Cobain cardigan, and were also overseeing the sale of the cape.

Most of the major international auctioneers — Bonhams, Sotheby’s, Christie’s — have departments dedicated to pop culture, entertainment memorabilia or “private and iconic collections”. Expert analysis and authenticating documentation are of particularly vital importance in this industry: an FBI operation in 2000 posited that over half of the items on the sports and celebrity memorabilia market were likely to be counterfeit.

“There’s so much serious money coming into this world,” says Martin Nolan, co-owner and executive director of Julien’s Auctions. Originally from County Roscommon in Ireland, Nolan worked on Wall Street for 13 years before joining Julien’s in 2005 and has been surprised to find it is an industry that seems to invert economic trends. “We find that in a recession we tend to do better,” he said. “That sounds crazy I know, but the people who have the stuff need money so they’re consigning it to auction, and we’re not selling anything that anybody needs, clearly: we’re selling to people that have sufficient disposable income that they are not impacted.”

Music, Nolan says, is particularly strong right now, and Julien’s has learned to host its rock ’n’ roll auctions in New York, “because the Wall Street guys who are making serious amounts of money and getting huge bonuses, they love their toys, and there’s nothing more cool than to have a John Lennon guitar on the wall, or Ringo’s drum kit in the conference room.”

The clash of corporate capitalism and rock rebellion is not lost on him: “You think about Nirvana, Kurt Cobain was so anti all of this world. He probably bought that cardigan for five bucks in a thrift shop. It sort of goes against everything he was singing about.”

But, says Nolan, the people who buy such things are in fact trying — like Superman reversing the Earth’s rotation in order to prevent an earthquake that will kill Lois Lane — to turn back time. “It’s 26 years since Cobain passed away, and the people that loved Nirvana then have gone on to lead successful lives, they’re professionals now, and 26 years later, they’re buying a memory. They’re buying their youth.”

2. Stefan

For close to a decade after Darvin had sold it, the Superman cape went dark, its whereabouts a mystery. In those same years, Christopher Reeve, who had gone on to star in a further three Superman films, fell from a horse and was left paralysed from the neck down and unable to breathe without a portable ventilator. A year after his accident, in March 1996, he made a surprise appearance at the Academy Awards in Los Angeles, greeted with a minute-long standing ovation. “What you probably don’t know is I left New York last September and I just arrived here this morning,” he said from his wheelchair, to both laughter and tears.

In 1997, the Superman cape reappeared in a “Collectors’ Carousel” sale of “Dolls, Toys, Hollywood and Rock ’n’ Roll Memorabilia” at Sotheby’s in Manhattan. How it travelled the breadth of America, from California to New York, and who brought it there, is difficult to determine: two representatives of Sotheby’s told me records from the time were not sufficient to identify and contact the consigner on my behalf; Dick Swan, who sold the cape for Darvin, could not remember who had bought it, only that it was an “irregular customer, not someone I knew well”.

On the morning of 19 December 1997, Stefan Park, then 28, was having breakfast with a friend in the dining room of their Manhattan hotel. They were on the final leg of a month-long trip that had taken them to Asia, Australia and the United States; New York was to be their last stop before returning home to Sweden. Stefan had grown up in Gothenburg, in a family of modest means and little academic expectation, but his natural abilities in physics, chemistry and mathematics had seen him hurtle into professional life at startling speed: university studies alongside high school at 15, a job in the research department of Volvo at 17, setting up his first company at 24 and becoming one of the first people in Europe to work with artificial intelligence and virtual reality. By his late twenties, he had worked hard, earned well, and was ready for a vacation.

As they ate their breakfast, the friend — a professional footballer whom Stefan prefers not to name — noticed an item on the news. It was about a jacket that had been worn by William Shatner as Captain Kirk in Star Trek; one of the iconic, maroon ones from the second, superior, movie Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan that came out in 1982. It was for sale in New York that very day. In fact, the auction had already started. As a self-confessed nerdy scientist, Star Trek was Stefan’s ultimate sci-fi passion. They ran outside and hailed a cab.

Stefan’s collecting interests had started small. As a child he was fascinated by space exploration; one day he thought he would love to have an autograph from an astronaut. You could buy one for not much: as little as $15 maybe. Then, he thought he’d like to have one from a cosmonaut too. And what about seeing if he could get an item of some kind from every living astronaut? There were only 270 or so; it couldn’t be too hard. Or what about a signed letter from Neil Armstrong that had actually been carried into space and back? Before long, Stefan had them all, and more.

When they arrived at Sotheby’s they were fast-tracked through the registration process, despite being two young guys in their twenties and perhaps not the most convincing of customers. They entered the sale room just before the jacket came up, and despite a bidding war, Stefan came away victorious. He was ecstatic from the win but there was still one auction lot to go. (He learned later that the item had also been featured on the breakfast news show, but he’d got in the taxi so fast he missed it.) He remembers some kind of a veil coming down, and a spotlight, and the shiny Superman logo, and realising that, for everyone else in the room, this was the reason they had come.

Stålman, as Superman was known in Swedish — a literal translation of “Man of Steel” — had been the comic that Stefan had grown up with. He’d read it since he was six. He’d seen the film at the cinema, sitting in the front row, second seat from the left: he’d always had a good memory for spatial settings and for dates. Reeve, he remembered, really looked like Superman. It was one of the few films where you could believe the actor and the character were one and the same. Still revved up from buying the Captain Kirk jacket, Stefan raised his auction paddle up and didn’t take it down.

Stefan bought the cape for $23,000. Back at the hotel that night, he and his friend had dinner. His friend wore the Captain Kirk jacket, he wore the cape. They ordered room service instead of eating in the hotel’s restaurant because, despite their giddiness, there were some limits to how nerdy they were prepared to be. The next day, he packed the jacket and the cape in his hand luggage and boarded a Concorde — faster than the speed of sound, though not a speeding bullet — to take him back across the Atlantic.

Over the years, Stefan kept his collection in a secure, climate-controlled storage facility in Gothenburg, away from humidity, sunshine and animals. When he got married and had children, one of the few items he would bring home from time to time was the cape. He would put it on his kids and let them fly around the house. He tried to interest them in science and space exploration with little success, yet despite never having read the comics, they knew who Superman was. He wasn’t sure what caught their attention: the fact that he could fly? His dualistic identity? His invulnerability? (On 10 October 2004, Christopher Reeve, who had devoted himself to promoting research into spinal cord injuries, and had set up a prominent foundation to improve the quality of life of people with disabilities, died from sepsis. He was 52.)

As Stefan approached his fifties, the logistics of collecting started to get to him. The storage facility was expensive, and he realised there was an upper limit to how much stuff he could have. His wife would make occasional jokes about the A&E TV show Hoarders, a reality series about people with compulsive hoarding disorder, and while he wasn’t stockpiling old newspapers, he could see her point. Finally, last year, he decided the time had come. He contacted Julien’s Auctions, and selected some items he thought might attract interest. It was an emotional decision, but he knew the cape was one of them.

“When I meet a consigner coming in to sell, I always say, ‘When is the time to start letting go?’” says Martin Nolan of Julien’s. “Because it’s a burden. Especially because now these items have become so valuable.” For many artefacts, the window of opportunity is specific and not necessarily very long. “We did an auction for Bob Hope,” says Nolan, “who would have been 103 if he’d been alive when we did his first auction, and maybe 110 when we did his second. As big as he was — he hosted the Academy Awards for 19 years — we found the fanbase that loved him were not acquiring any more. They’re trying to get rid of their own stuff. That’s a thing we look at and encourage: to think of people when they’re still relevant, and remembered.”

Superman: The Movie came out in 1978. Those who saw it as children, for whom it may have been a formative cultural experience, are now in their late forties and fifties. They might be buying now, but for how much longer? Perhaps Superman had risen as far as he could go?

Nolan was cautiously optimistic. “What I always say is, ‘Don’t buy it thinking it’s going to be an investment. Buy it because you love it, because of the emotional attachment, the history, the storyline’. But it’s very likely if you’re buying something iconic, it will continue to appreciate in value,” he said. Not surprisingly, given his line of work, he felt the cape would be one of those rare exceptions. “Superman will be one of those movies that will stay the course.”

3. Joe

On 16 December 2019, the sale room at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills, where the “Icons & Idols: Hollywood” auction was being held, was a little quiet. That was fine, it was a Monday after all, and there were enough online and phone bidders pre-registered to suggest some excitement over what was about to take place.

Nevertheless it started slowly. A series of model locomotives from the collection of Neil Young failed to get much interest, though things perked up when Charlie Chaplin’s hat went for $7,680. They leapt again when two paintings by Frank Sinatra — a stormy Hawaiian seascape, and a surprisingly competent black, white and red abstract that called to mind playing cards and poker chips — soared above their estimates to sell for $21,250 and $75,000.

As the lots ticked by, a Captain Jean-Luc Picard uniform worn by Patrick Stewart in Star Trek: The Next Generation went for an unexpectedly high $28,800, as did, selling at $19,200, a Fender Stratocaster featuring Hugh Hefner’s signature and a naked Marilyn Monroe. The Nike T-shirt from Forrest Gump went for just over its estimate to sell for $2,560, though neither the Bilbo Baggins pipe nor the Steve McQueen motorbike met their reserve price, and they were removed from sale (too early? Too late? Only the market knows).

When Joe Ingold’s phone rang it caught him off guard. It was Mitchell Kaba, director of fine art at Julien’s, ready to field his phone bids for the cape, which was just a few lots away. Joe had registered as a bidder a week before but was working in New York and had miscalculated the time difference: he wasn’t expecting the lot to come up for another hour or so. He quickly took himself to the office he keeps at one of his client sites, a hospital — he works as a financial consultant for healthcare companies — so he could focus fully on the call. Though he occasionally uses online bidding, with an item of this importance he wasn’t willing to risk a patchy internet connection.

Joe started collecting sport memorabilia 20 years ago, with a football signed by legendary NFL running back Walter Payton. Soon he branched into film and has now accrued some eye-catching artefacts, though he limits himself to key pieces from movies that mean something to him. His collection includes one of the Wicked Witch of the West’s hats from The Wizard of Oz (there are four); a helmet from Saving Private Ryan, worn and autographed by Tom Hanks; and the heavily weathered letters spelling “Orca” once nailed to Quint’s boat in Jaws.

As a kid in Chicago, he had played a lot of baseball, and was a trombonist in the school band, though he’d also read Batman and Superman comics, like any kid his age, and watched Superman: The Movie many times. Something about Superman as an iconic American figure — truth, justice and the American way — just resonated with people, and it resonated with him; the values that he stood for were important. Joe had seen Superman items come up for sale before, but he was wary, because he knew there were a lot of false pieces on the market. He’d even come close to buying a cape before, one he’d seen for sale in Las Vegas 10 or so years ago, but felt the documentation wasn’t up to scratch.

This cape, though, was the holy grail. It was the kind he’d been waiting for. The DC Comics contest gave it the provenance that Joe needed, and the Christopher Reeve connection was important as well: the fact he’d not only worn it in the film but had handpicked the competition winner. Like everyone, Joe could appreciate what Reeve had been through. The misfortunes he’d suffered, so soon after portraying Superman, enabled people to reflect that we’re all human. Reeve’s story made the character of Superman seem more human too.

Joe let the early bids get out of the way: $85,000… $100,000… $110,000. He came in at $120,000 — he thinks so anyway, it’s still a blur — and it quickly came down to him and an internet bidder in China (in recent decades the influence of buyers from Asia, China in particular, coupled with the reach of the internet, has had a transformative effect on the auction market, as it has on more or less all forms of commerce). The Chinese bidder offered $130,000. Joe came back with $140,000. The Chinese bidder went to $150,000.

Joe needed to catch his breath: $150,000 had been the notional limit he had set himself, though looking back now, he’s not sure he ever meant to stick to it. But there was no time to think, things were moving too fast, and this was his one chance in a lifetime.

“Do you want to do 155?” asked Kaba.

“All right,” said Joe. “155.”

Four minutes after the lot was introduced, the hammer fell. “Sold, sold, sold!” shouted the auctioneer. Martin Nolan, sitting next to Kaba, could hear the shrieks coming down the phone.

At the time of writing, Joe hasn’t received the cape though he has paid for it: with the auction fees the final bill was $193,750 (£148,000), at the top of the pre-sale estimate of $100,000 to $200,000. Even though it all happened at lightning speed, and Joe is financially comfortable, the cape is still a purchase to be taken seriously. In the regular run of things, if he were buying something for, say, $10,000, he would think about it, ponder it, research it; the idea that he spent almost $200,000 in a few minutes still feels incredible. When he first started collecting, he’d thought about his purchases as investment diversification, but lately that has fallen by the wayside. Now it’s about building up the best collection that he can have, because, as he’s gotten older, he’s had to think, “What is it that I enjoy in life?”

Joe is 55, so has some working years left, though retirement is already on his horizons. Because he and his wife do not have children, he knows he’ll eventually need to decide what the fate of the cape should be. It might get sold onto another collector when he dies, or go to a museum, such as the much-delayed Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in LA (he has already agreed to loan it the Wicked Witch’s hat). Or perhaps, he’ll sell it in his lifetime, to save his wife from having to untangle the complicated details of his estate.

But those are questions for the future. In the meantime, once he has the cape, he’ll start working out how to display it. He might design an elegant, wood and glass cabinet for it and place it somewhere around his house, as he’s done with the Wicked Witch’s hat and Tom Hanks’ helmet. Or he might think of a more unusual treatment, such as the Orca letters, which he has arranged on a specially designed wooden plaque hanging over a fireplace.

The important thing is to preserve it. Joe sees himself not as the owner of the cape, but as its temporary custodian, with a duty to make sure it suffers no damage while under his care. But before he seals the cape away to protect it for generations to come, he will enjoy the time when it is only his: when he can see it and touch it and try it on; when he can feel, if only briefly, what it is like to be Superman.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox

Miranda Collinge is the Deputy Editor of Esquire, overseeing editorial commissioning for the brand. With a background in arts and entertainment journalism, she also writes widely herself, on topics ranging from Instagram fish to psychedelic supper clubs, and has written numerous cover profiles for the magazine including Cillian Murphy, Rami Malek and Tom Hardy.