Creativity is a mercurial thing. Not just because it can be difficult to define (and subjective) but because even to a singular artist, its meaning can change from day to day. Of course, much of art is about exploring the unknown and pouring every ounce of passion you have into what is being made. But what does that mean when it comes to artistic collaboration; when the unknown is a maker whose work you admire, but whose approach may be very different to your own?

This is exactly the conundrum British artists Walter & Zoniel and Tishk Barzanji found themselves in when they were tasked with creating a piece of art for handcrafted whisky brand The Balvenie, a distillery which prides itself on showcasing the specialness of things made by hand. To complicate matters further, the brief was rather open-ended. All that was required for The Makers Project (an exploration and celebration of modern creativity across many different disciplines) was to create a piece of work that captured the spirit of craftsmanship across varying categories, celebrating the human elements that give rise to exceptional work through collaboration. So, where to begin?

“We’re both big whisky fans anyway,” reveals Zoniel. “There’s always a way,” she adds of finding an ‘in’ to the creative process. Over a 10-year partnership with Walter, the pair have amassed a large book, literally labelled ‘The Big Book of Ideas’ which they draw from for each project. “It’s hard to not have ideas for things. Your mind can spiral off with loads of ideas,” Zoniel says.

“We build big installations, and at any one time we have four, five or six different installations we want to build, as well as print stuff we’re working on,” explains Walter. “So, it’s more like adapting our ideas to suit a given brief.”

Walter & Zoniel live, work, sleep, breathe, eat and create together, 24 hours a day. Among the many things they have built are surrealistic installations including filling a derelict building with tanks of jellyfish in Liverpool, painting rocks on Brighton Beach and designing an immersive meditation that encourages the participant to explore their personal relationship with different artworks.

Their partner in this project, Tishk Barzanji, is a visual artist based in London, whose work touches on the modernism and surrealism movement. At 33, Tishk is the younger of the three by seven or eight years, something which mirrors the relationship between the outgoing Balvenie Malt Master David C. Stewart MBE – who has had an astounding 60-year career with The Balvenie (making him the longest serving Malt Master in the industry) – and his talented co-creator, Kelsey McKechnie. Like Stewart and McKechnie, Walter & Zoniel and Tishk are craftspeople at different points along their creative journeys who are coming together in a collaborative way.

Putting trust in the creative process

As with any creative endeavour, the key is to trust the process. It’s an idea that very much applies to Tishk’s own approach. “I try to take inspiration from the past and see how it can relate to the future,” he explains. “In terms of my influences, they’re always from me going out exploring and taking sketches. It’s always a weird object, or an interesting interaction with someone. Usually something no one else would see; it could be a curve in the road.”

“I think [collaboration] is inherent in the nature of our work,” adds Zoniel. “As Tishk has said, it’s about connection. It’s important to us that whatever we create will form a connection with whoever is receiving that. The end point is our starting point in a way.”

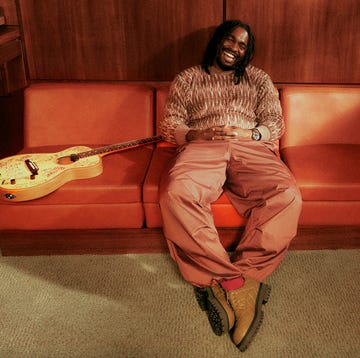

In terms of literal starting points, Tishk and Walter & Zoniel came to their relative crafts in different ways, but with some similarities along the way. Tishk only began creating art around five years ago, after a doctor said photography might be a good way to help with the migraines he was suffering from. This quickly led to painting and graphic design. “It just kinda happened out of nowhere,” Tishk says. “It wasn’t announced as a full-time career.”

Today, his work touches on colour and deconstruction. “My doctor talked about having these doors in my head when I’m not feeling well, to escape,” he says. “I ended up using that a lot in my work, stairs and doors.”

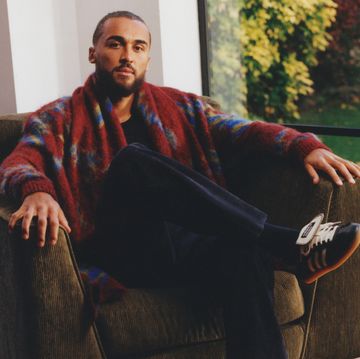

Walter, 41, studied physics at degree level before painting large-scale photographs on walls around London in the dead of night. He then went on to building giant cameras before, in his words, “someone said, ‘Hey you should start making art!’ and I never looked back”.

“That was me who said that,” Zoniel chimes in. “I had a similar experience to both of these guys. I grew up in a really creative family and art has always been part of my life, but I never thought I would be an artist. It just never occurred to me.”

Transforming pain into art

After suffering from meningitis as a child, Zoniel went on to serve under a Buddhist master studying thangka painting, an experience she said brought her thinking around 360 degrees to seeing art as “this perspective of how we relate to one another”.

Like Tishk, Zoniel was able to turn an illness into an asset. Unfortunately, she contracted meningitis again – and Covid – in late December 2021. “I got zipped into this massive tent, then I got isolated from the isolated people,” she explains. “I was in the pitch black for 10 days in hospital; I didn’t know what anyone looked like.”

The experience has left Zoniel extremely photophobic and there is only a certain amount of time she can spend in the light each day, as evidenced by the large Anna Wintour-esque glasses and hat she wears during our conversation. “That’s been full-on for eight or nine months now,” she says. “I related to what Tishk said about the relationship between fragility and creativity. [When I was ill], first I was deeply inspired. Then, all of a sudden, I was devoid of any form of stimulus and my mind was crazy with ideas, even though I was in a lot of pain.”

Despite illness, the project has been able to continue with the three in early talks about what the finished product may look like. “We kinda know what we’re aiming for,” Tishk reveals. “My work has a lot of anonymous characters in it and we thought we’d take that out into the real world where people can actually see it.”

The work is likely to involve 3D sculpture, something Walter & Zoniel are intimately familiar with, but is new to Tishk. “I’ve never worked in 3D so I worry I won’t be able to capture what I’ve imagined,” he says. “The way they go about their work is very different to me and it’s already made me think about my approach in the future. I’ve always liked to collaborate but only when it made sense, not just for the sake of it.”

At the beginning of a project, Zoniel feels the same excitement and fear. “The thing that’s scary is the thing that’s exciting!” she says. “How are you gonna actually make it?”

Finding their inspiration

Tishk finds inspiration comes at “weird hours” at home. For Walter, inspiration comes in the bath. For Zoniel, train journeys help her relax and invite inspiration. All three have taken advice from their peers, whether that’s through going for a pint and getting into the nitty gritty of the creative process, or by osmosis and appreciation of other artists’ work.

As for the advice they might give younger artists, Tishk says, “No one’s journey is the same, but keep doing what you like. It’s a cliché but it’s true. How passionate are you to keep going, even though you might not get immediate results?”

Walter thinks the most important thing is to keep making work, and to not worry about societal expectations of where your career ‘should’ be. “If you’re passionate about something, it doesn’t feel like work,” he says. “Keep making something you believe in, and if you believe in it, someone else will believe in it. It’s as simple as that.”

This passion and self-belief are encapsulated by The Maker’s Project and are two key ingredients in The Balvenie. Through this process of shared passion, its Makers are able to dramatise the uniquely human difference created when Makers pour their hearts into their work.

Zoniel puts this eloquently. “[Creativity] can be like entering survivalist mode, but the other side of that is love,” she says. “You have to be in love with what you do. It’s that purity that is above and beyond everything else.”

Discover the taste of creativity with The Balvenie and The Makers Project