How far would you go to protect a recipe for fried chicken? If you set up Bao, a restaurant in Soho, central London, infamous for its patient queue of would-be diners, you might just surprise yourself. In the original restaurant’s early days, the three founders — Erchen Chang and siblings Wai Ting Chung and Shing Tat Chung — would suit up in gloves, masks and lab coats to mix the spices themselves, ensuring the recipe wasn’t leaked. But as Bao expanded and demand soared, that cloak-and-dagger approach became unsustainable. They eventually sourced an external producer, though, naturally, an NDA was signed. With the release of the restaurant’s first cookbook, Bao, this month, that fried chicken recipe is about to be common knowledge.

“When you open something successful, you claw onto the thing that is successful,” Shing Tat Chung says, sitting with his sister, Wai Ting, and his wife, Chang, at a table at Bao King’s Cross, which opened in 2020. He could be talking about any number of things that made the Taiwanese joint an instant hit. There’s that chicken, a much-requested hot sauce, and, of course, the bao: fluffy, cloud-like steamed buns. The founders’ heritage may also have contributed to that early secrecy: the Chung siblings grew up in Nottingham, where their family ran Cantonese restaurants, but their parents are from Hong Kong. Chang, meanwhile, spent her childhood in Taipei, Taiwan before moving to the UK at 14. “The culture back home is to keep your recipes guarded,” Shing Tat explains. “There’s not many cooks who will just tell all.”

Since the first restaurant opened on Soho’s Lexington Street in 2015, four more Bao outposts have launched across London, each with a distinct, design-led identity. The King’s Cross café, inspired by Taiwanese tea rooms, is lit up with Isamu Noguchi lamps, while the Borough branch has a basement karaoke bar and viewing window inspired by Paris, Texas. The (fairly safe) gamble is that even if people can make the dishes at home, they will still visit the restaurants for the vibe. “We realised that people go to Bao because of everything else we do as well,” Shing Tat says. “It’s not just about the recipes.”

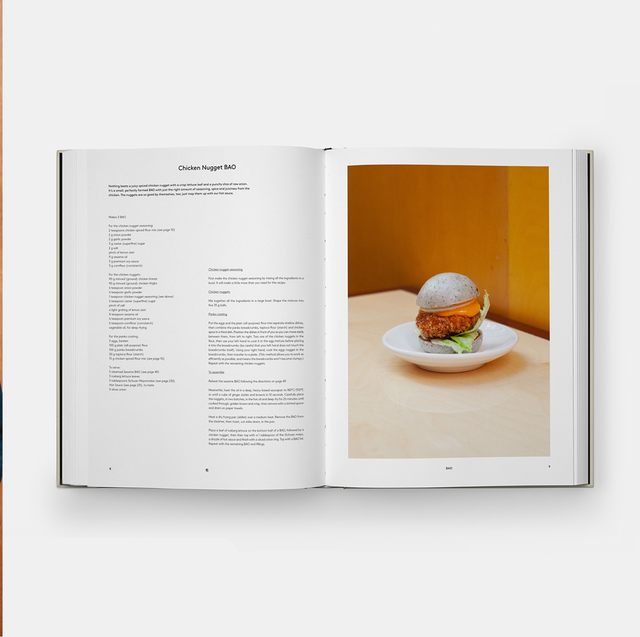

Another reason to still pop in? These dishes — which include all current and former menu items, plus a few surprises — are not exactly the stuff of mindless midweek suppers. With a laugh that hides a warning, Shing Tat calls the recipes “labour intensive”. They require a very well-stocked cupboard, technical prowess, and a lot of patience. The drinks, all pleasingly retro, require a mastery of foams.

Still, it won’t matter too much if Bao remains on coffee tables. The book delves deep into the restaurant’s thoughtfully curated and well-branded universe, such as its signature line

drawing of the “lonely man”, a mysterious, solitary figure chowing down on a bao. You may have seen him at a Bao restaurant, on a Bao tote bag, or a Bao T-shirt. He has his own calendar.

This lonesome diner has had a big impact on the Bao restaurants, where prime counter seats hope to encourage solo eating. At the Soho outpost, you (singular) can even order from the “Long Day” menu. (Recommended time and place? 2pm, bar seat.) “The menu tells the story of a perfect moment in Soho, when you can escape the hustle of Soho into the bustle of Bao Soho,” Shing Tat says. “That’s how we see the lonely man: having the perfect moment at Bao, appreciating the mastery of the dishes, and also having a perfect moment of solitude.” Now, with the new cookbook, Bao’s lonely man can treat himself to the occasional quiet night in. ○

‘Bao’ by Erchen Chang, Shing Tat Chung and Wai Ting Chung (Phaidon) is out on 2 March