Over the past few weeks, the world has gone mad for little white pills that some believe offer the best weapon we have against coronavirus. Conversely, they may not work at all. The chemical compound they contain, hydroxychloroquine, is the subject of Facebook groups and conspiracy theories, petitions and political debates. The clamour to get hold of it is so great that this perfectly legal drug is available for sale on the dark web alongside cocaine and heroin. So how did we get here?

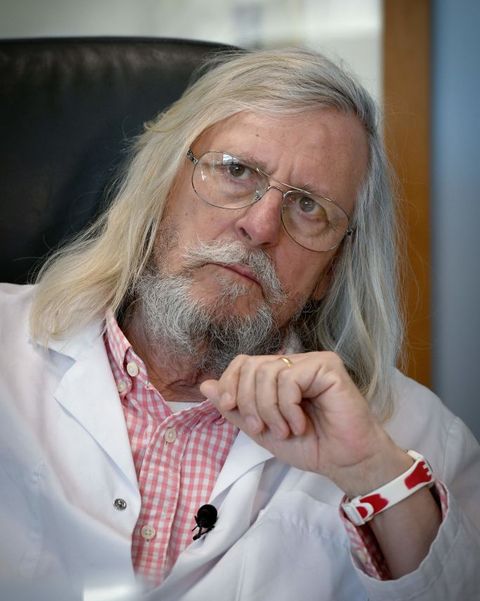

Interest in the drug, which we have been using for decades to treat malaria and other diseases, has been fuelled by celebrity enthusiasts like Elon Musk and Donald Trump. But trace the global hype back to its origins, and you eventually reach a maverick, climate-sceptic, proudly anti-establishment scientist from the south of France. The story of Didier Raoult is about what happens when dodgy science collides with collective desperation. It’s also the tale of how a 68-year-old microbiologist became a very unlikely figure in the online culture wars.

When Trump took to Twitter to hail hydroxychloroquine as potentially “one of the biggest game-changers in the history of medicine” on 21 March, he was citing a deeply flawed study by Raoult. For weeks, the French professor has been hammering home the drug’s potential in YouTube videos that have racked up millions upon millions of views.

The evidence that this drug is effective against Covid-19 is flimsy at best. British doctors have been strongly urged not to prescribe it until we get results from the various clinical trials that are testing hydroxychloroquine around the world, the biggest of which is taking place in the UK. But as medical authorities dithered, Raoult seized the initiative last month by announcing he would start giving hydroxychloroquine to coronavirus patients at his hospital in Marseille. If this was in direct defiance of government advice, Raoult didn’t give a damn. His duty as a doctor, he said, was to treat the sick with the best treatment available. Soon, (socially distanced) queues were forming around the block.

This gung-ho approach has made Raoult a hero to those convinced that hydroxychloroquine is a magic bullet. The professor has nearly half a million supporters in one Facebook group alone; he is popular among non-conformist internet communities, from anti-vaxxers to the far-right. In his native France, Raoult has become the face of opposition to the government’s coronavirus strategy.

The fact that he’s from Marseille boosts his anti-establishment appeal. The city likes to see itself as a Mediterranean rebel bastion in a country dominated both culturally and economically by Paris. Eric Cantona, Marseille's favourite son, spoke for many in the region when he hailed Raoult as a “phenomenon”.

“You’ve got these Parisians with their suits and ties, treating him like he’s a charlatan,” the Manchester United legend said in a recent video, between mouthfuls of what appeared to be creamed leeks. “A charlatan? He’s one of the best researchers in the world.”

Raoult says he is too busy saving lives to speak to journalists, and multiple requests for an interview for this piece went unanswered. But during infrequent media appearances he appears confident of being proved right about hydroxychloroquine. “The criticism and the gossip on TV, you have no idea how little I care about it,” he told Hervé Vaudoit, a local journalist who has known him for 25 years. “I know how this will end.”

The coming months will decide whether Raoult is remembered as a hero or a villain. Clinical trials may confirm that his recommended cocktail – combining hydroxychloroquine with an antibiotic called azithromycin – does indeed work, cementing his legacy as the daredevil doctor who identified the best treatment for the coronavirus pandemic. If it doesn’t work, he could go down as a snake oil salesman whose purported cure killed the vulnerable.

The French professor is almost too well cast as this pandemic’s anti-hero. Take off the lab coat and Raoult wouldn’t look out of place trying to sell you crystals in the Healing Field at Glastonbury. He wears a goatee and a thick ring, in the shape of a skull, on his little finger. “When I asked him what the hair was about, he said it was to fuck with them,” Vaudoit tells me, referring to the senior officials who have been in constant conflict with Raoult for years. “He’s always enjoyed being provocative.”

And yet there’s nothing wacky about Raoult’s demeanour. His YouTube videos are sober and scholarly, littered with data and charts. He speaks calmly and convincingly. Though he seems like a maverick, he is also one of the most admired experts in his field. He seems to simultaneously convey a rebel attitude and scientific authority. In Didier Raoult, people who normally distrust experts have found an expert they can get behind.

Didier Raoult's popularity in obscure 4Chan forums can make him seem like a quack. So can his numerous climate change-denying magazine columns, the book he wrote questioning the theory of evolution, and the fact that he has published a truly mind-boggling quantity of research findings over the course of his career. His name appears on some 3,000 peer-reviewed papers and he publishes more in a month than most researchers put out in a lifetime.

“This is one of the secrets of the system put in place by Didier Raoult: publish at all costs,” Le Monde newspaper wrote in a profile that raised numerous questions about his academic record. And while this strategy has made Raoult the most-cited expert in his field, many have raised doubts that anyone could maintain quality and rigour when publishing in these quantities. Hundreds of his papers have been published by journals managed by his own co-authors and colleagues. In 2006, the American Society for Microbiology banned Raoult and his team from publishing in any of its journals for a year, on suspicion of fraud. And in 2018, France’s top research authorities withdrew their recognition of two laboratories under Raoult’s supervision after an investigation found serious problems with their methods.

And yet some of Raoult’s research is highly respected. Though he came late to medicine, having spent two years as a sailor on merchant navy ships before deciding to become a doctor, he won international recognition in the Eighties for his work on rickettsia, a bacteria that can spread human diseases via fleas, ticks and lice. He was also part of a team that produced pioneering research on giant viruses in the early 2000s, which gave birth to a new mini academic field.

His Stakhanovite publishing record is tied up with his ambition, says Vaudoit: “A lot of the doctors he trained with wanted to be the best in Marseille. Raoult wanted to be champion of the world.” And he sought more than just academic recognition. For years, he dreamt of setting up a state-of-the-art infectious disease hospital, eventually launching the Méditerranée Infection hospital in 2012. Even his enemies are impressed that he managed to turn that dream into a reality.

Its vast, modernist building stands out against the Marseille skyline, which was always Raoult’s intention. Built with an investment of €72 million, it is gleaming proof to the Paris elites that great things can happen outside the capital. “It feels more like you’re walking into the headquarters of a big company, or an architecture school,” says Vaudoit.

The idea was to create a hospital that could offer world-class treatment for infectious diseases and produce leading academic research. Raoult’s team receives millions of samples of bacteria and viruses for analysis each year, the most deadly of which – anthrax, bubonic plague – are handled at the top of the building. “The higher up you go, the more dangerous it gets,” runs an old joke among the staff. “We keep the most virulent germs on the third floor, and the management on the fourth.”

Few hospitals were better equipped to deal with coronavirus when the pandemic arrived in Europe. Méditerranée Infection has a massive diagnostics lab and a third of its rooms can be sealed off for patients carrying highly infectious diseases like Ebola. The hospital quickly organised a massive Covid-19 testing programme that led Raoult to boast that Marseille’s residents were “the most-tested population on Earth”. The speed and efficiency of this operation came as an embarrassment to the French government, which has so far failed to implement mass testing of the kind seen in Germany or South Korea.

At the same time, Raoult and his team had begun a small clinical trial to test the effects of hydroxychloroquine on coronavirus patients. Thanks to some highly misleading comments from a Fox News commentator, that study would soon catch the attention of Donald Trump. And Raoult would suddenly go from being well-known for a microbiologist, to the darling of a global internet movement.

Hydroxychloroquine was born out of centuries of conquest and conflict. In the 17th century, Spanish colonists in Latin America learned of a tree bark that was used by indigenous people to treat fever. They took it back to Europe, where French chemists worked out how to extract its active ingredient, quinine, in 1820. This compound proved much more potent as a malaria treatment than simply grinding up the tree bark, and its discovery helped power the expansion of European empires across malaria-ridden parts of the world. Quinine has a bitter taste, and British colonial officers in India discovered it went down better when mixed with water sweetened with sugar and limes. It became known as tonic water, and it was found to be delicious with an added dash of gin.

Quinine was being produced on an industrial scale by the start of the Second World War, when governments were anxious to prevent malaria spreading among soldiers fighting in the Pacific. But the drug could be toxic if taken in large doses – sometimes even causing blindness – and the war sped up efforts to synthesise safer versions. Tinkering with quinine, German scientists managed to extract a more effective drug, chloroquine. By the Fifties we were using an even safer version: hydroxychloroquine.

Over the ensuing decades, researchers discovered that it could be used to treat a range of other diseases beyond malaria, from rheumatoid arthritis to lupus. Hydroxychloroquine is among the most-tested drugs on earth and as such we have a good grasp of its side-effects, which range from nausea to heart problems. “There are very few drugs that we understand so well,” says the geneticist Jean-Michel Claverie, who worked with Raoult until the pair had a spectacular falling-out in 2008.

The theory that hydroxychloroquine could fight coronavirus is based on solid science. The drug reduces the acidity of our cells, which makes it harder for viruses to attack them. In a test tube, variants of chloroquine have been found to help cells fight off a range of different viruses, from Ebola to HIV. But researchers have failed repeatedly to get them to work in humans.

Still, Chinese doctors had seen tentative positive results from treating Covid-19 patients with chloroquine, and Raoult was keen to test out its safer sister-drug in Marseille. In early March, just as his hospital was starting to fill up with coronavirus patients, his team carried out a clinical trial. Some of the patients were given hydroxychloroquine; others were also given the antibiotic, azithromycin. The final figures were startling: 70 per cent of patients who took hydroxychloroquine were cured after six days, compared to only 12.5 per cent of those who didn’t. The results were even better for a handful of patients who were given the drug alongside the antibiotic; the drug cocktail had a 100 per cent success rate within just six days.

On 18 March, two days before the study was published in the International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, a New York lawyer and blockchain entrepreneur named Gregory Rigano hailed the results during an appearance on Fox News. Rigano, and a doctor-turned-bitcoin-investor named James Todaro, had already appointed themselves as Silicon Valley’s chief hydroxychloroquine hype-men, co-authoring a widely shared Google Doc that made the case for the drug.

“I’m here to report as of this morning, about five o’clock this morning, a well-controlled, peer-reviewed study carried out by the most eminent infectious disease specialist in the world, Didier Raoult,” Rigano told Fox News host Tucker Carlson. “A well-controlled, peer-reviewed study that showed a 100 per cent cure rate against coronavirus.”

“I only know what you're telling me,” Carlson replied. “But I do know it's very unusual for a study of anything to produce results of 100 per cent. I mean, that's remarkable, isn't it? Or am I missing something?”

“That is remarkable,” Rigano replied. “What we're here to announce is the second cure to a virus of all time.”

Putting aside the question of whether tech bros should be treated as credible medical commentators, Rigano was correct when he said the study showed a 100 per cent cure rate for patients who took Raoult’s drug cocktail. But it wasn’t long before experts were raising serious problems with the way these results had been presented.

In all, 26 patients were given hydroxychloroquine, of whom six were also given azithromycin. And yet only 20 of these people made it into the results. Three were transferred to intensive care; another died. One more decided to stop taking the drug because it made them nauseous, and another simply left the hospital. Since the study relied on being able to test the presence of the virus via daily nasal swabs, these patients were left out of the final data.

This was problematic enough, but the trial had other major design flaws too. “The biggest one was the lack of randomisation,” said Darren Dahly, a lecturer in research methods at University College Cork.

At their most basic, patients in clinical trials are split into two groups to assess whether a drug actually works: those who take it, and those who don’t. Randomising means allocating the patients at random to these two groups, to help ensure they are as similar as possible. Otherwise, even if you get dramatically different results for each group, you can’t say for sure whether they were caused by the drug. Some other factor might be responsible: maybe the group that took the drug were younger, or healthier.

Raoult’s team did not randomise. All of the people who were given the drugs were patients at his own hospital, but the control group were studied at other hospitals in the south of France. The group that took the drugs was also significantly older, with an average age of 51, as opposed to 37. “There could be a bajillion reasons why the groups had different outcomes,” Dahly told me. “My own opinion is that these results were completely meaningless.”

High-quality trials also tend to be performed on large groups of patients. Raoult only tested his drugs on 42 people, which raised the possibility that the results might turn out differently if it was attempted again. Indeed, when another French team tried to replicate it a couple of weeks later, they got completely different results. They found no evidence that Raoult’s drug cocktail made any difference at all.

Further criticisms of the study piled up; the International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, which runs the journal it was published in, said it didn’t adhere to expected standards. But the complaints were difficult to hear over the cacophony of excitement.

Rigano’s Fox News appearance lit the touchpaper. Within hours, Raoult was bestowed with that rarest of scientific honours: having his research cited in a Trump tweet. “HYDROXYCHLOROQUINE & AZITHROMYCIN, taken together, have a real chance to be one of the biggest game changers in the history of medicine,” the US president wrote in a post retweeted more than 100,000 times. “H works better with A, International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents.”

Within days, governments around the world were coming under pressure to immediately authorise the use of hydroxychloroquine against coronavirus. “No country in the history of the world has ever authorised a treatment on the basis of a study like this one,” French health minister Olivier Véran complained on 21 March.

And yet two days later his government had backed down and said doctors could give hydroxychloroquine to the sickest coronavirus patients. Raoult had gained a curious political power; Emmanuel Macron even flew down to visit the rebel hospital in Marseille, hailing the professor as a “great scientist”.

International panic-buying ensued. A scared American couple in their sixties, who had heard about chloroquine on television, attempted to self-medicate by drinking a cleaning product that contained a variant of the compound. The man died, and his wife was left in a critical condition. The US bought and stockpiled 29 million doses. Meanwhile, people with lupus, an autoimmune disease that has long been treated with hydroxychloroquine, began struggling to get hold of their usual prescriptions.

The Marseille team has since carried out two more clinical trials, both of which supposedly prove the efficacy of Raoult’s drug cocktail. Both have been heavily criticised for their methods. While they were bigger than the first attempt, involving 80 and 1,061 patients respectively, neither study had a control group: every patient was given hydroxychloroquine and axithromycin, which means there is no way of knowing what would have happened if they hadn’t taken them.

Raoult has derided his critics as “methodological maniacs”. He is prescribing the two drugs to all patients who test positive, and he is unapologetic. “Before anything else, I am a doctor,” Raoult told Vaudoit. “I took the Hippocratic oath in 1981 and my duty since then has been to do what I think is best for the sick, based on what I know and the state of science. This is what I’ve done for 40 years and what I’m doing right now with my team: treating the patients who show up, as best we can.”

A coronavirus vaccine could be years away. Rigorous clinical trials of hydroxychloroquine would take months. Thousands will die in the meantime. Raoult believes we are at war, and a war requires war medicine. If this cheap, plentiful drug has been used safely against numerous diseases for decades, should we not be trying it out on the new virus that is ripping our world apart? What’s the worst that could happen?

What Raoult is proposing is an informed leap of faith and many doctors on the frontline are following his lead. Surveys suggest huge numbers of doctors around the world have been prescribing chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine to Covid-19 patients. Raoult’s army of internet fans are also seeing an appealing narrative: a courageous doctor doing the best he can to save lives, while bloodless academics debate the niceties of scientific methods. Experts who have called for more rigorous evidence on hydroxychloroquine have found themselves accused of prioritising procedure over flesh-and-blood humans. What would you have us do, ask the enthusiasts: watch people die while your beautifully designed clinical trials take months to confirm what Raoult already knows?

The case for rigour is not helped by the anti-expert mood that has accompanied the rising populism of recent years. Michael Gove told us in 2016 that Britain had had enough of experts. Nigel Farage, when he wasn’t railing against Brussels bureaucrats, delighted in trashing the World Health Organisation as “just another club of clever people” who want to bully you. And the leader of this movement is also, sadly, the leader of the most powerful country on earth.

Donald Trump rose up on, and encouraged, this tide of anti-intellectualism. He is so contemptuous of expert advice he once stared straight into the sun during an eclipse. He has mused publicly that injections of bleach might scrub the coronavirus from your lungs, since it works that way in your toilet bowl (the maker of Dettol was forced to issue a warning not to follow the president’s advice). Trump has encouraged millions of people to feel like it’s OK to deride academics as ivory tower pen-pushers, and that it’s OK to dislike them for acting like they know better than you. How many people this attitude has killed will only become clear when the history books are written.

In this climate it has not been easy for mainstream medical experts to warn against the crucial danger of the hydroxychloroquine hype: that it could well be diverting resources from investigating other treatments, which might save more lives. On 23 April, Rick Bright, the US doctor in charge of finding a coronavirus vaccine, was fired. He claims he was demoted from his position as director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) after facing relentless pressure to direct money towards hydroxychloroquine over other options.

“I believe this transfer was in response to my insistence that the government invest the billions of dollars allocated by Congress to address the Covid-19 pandemic into safe and scientifically vetted solutions, and not in drugs, vaccines and other technologies that lack scientific merit,” he said in his statement. “I am speaking out because to combat this deadly virus, science – not politics or cronyism – has to lead the way.”

That belief is echoed even by those who are trying to find out if the drug actually works. “We don’t know that hydroxychloroquine is safe in this context,” insists Martin Landray, deputy chief investigator on the UK’s Recovery clinical trial. “We don’t know that it works, and it’s distracting us from thinking about what other treatments might work. Now is not the time for faith healing.”

Both of Raoult’s favoured drugs are among various treatments being looked at by Recovery. But crucially, the UK study is randomised, with the different drugs allocated arbitrarily among patients at more than 150 hospitals. It is also the biggest Covid-19 trial in the world, having recruited 6,000 patients already – which gives it a fighting chance of being able to say definitively whether one of the drugs works better than the others. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin, which are being studied separately, may turn out to be among the best. Or they may turn out to be useless.

Recovery is among dozens of trials testing drugs that are seen as promising, including ones used to treat HIV and Ebola. But the hype around hydroxychloroquine has distorted the public discourse to the point where there is disproportionate pressure on health authorities to launch trials for the drug.

The craze has also had knock-on effects on more rigorous studies. Europe’s Discovery trial is attempting to recruit 3,200 patients in at least seven countries, testing a range of different drugs. But in some French hospitals, “four out of five patients are declining to take part and refuse any treatment but hydroxychloroquine,” Jean-François Bergmann, a former head of infectious disease at the Saint Louis Hospital in Paris, told Science magazine. The trial has already fallen victim to what he called “medical populism”.

In recent days, both Trump and his allies at Fox News appear to have gone off hydroxychloroquine. It’s not clear why, although the shift came just as tests on 368 US army veterans hospitalised with coronavirus found a higher death rate among those given the drug than those who weren’t. There have been reports in France of patients dying of cardiac arrest; chloroquine trials in Brazil and Sweden were halted after patients began suffering alarming side effects, such as blinding headaches and irregular heartbeats.

Still, the hydroxychloroquine movement survives. Believers complain that these reports are overblown by the haters. The most zealous go so far as to suggest a propaganda war is deliberately undermining the case for the drug. Hydroxychloroquine is cheap (although the branded version Plaquenil is still widely used, its patent has expired so it can be produced generically) and more expensive solutions, like vaccines, would obviously suit both big pharma and its investors. Wake up, sheeple!

To general horror from the medical profession, Trump’s attention has meanwhile turned to other potential cures – ones that could have potentially disastrous consequences if people tried to self-medicate. Could we perhaps blast the virus with UV rays, he mused on 23 April. Could we inject ourselves with disinfectant?

The idea that there might be a miracle cure for coronavirus is tremendously seductive to populist leaders. Brazil’s far-right president Jair Bolsonaro has been just as enthusiastic about hydroxychloroquine, to the point where he posted videos on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram that claimed the drug was totally effective. The social networks took them down, saying the Brazilian president had spread misinformation.

Trump adores easy solutions – build a wall! Make Mexico pay for it! – and he is a politician who understands the power of hope. Few slogans have proved as potent as Make America Great Again. Since the start of the coronavirus crisis he has peddled false hopes continuously, refusing to lay out just how long and fatal the pandemic could be. The virus could one day disappear “like a miracle”, he suggested in February. People need to wait just “a little bit longer” for businesses to reopen, he pleaded with the people of Georgia on 22 April. He has told people there are bountiful tests and supplies. Hydroxychloroquine, a drug that offers cheap, easy results, is the perfect Trumpian response to this crisis.

And who knows, he might be right. The history of modern medicine is one of people testing out new ideas and seeing what works. That’s how we got penicillin; it’s how vaccination was invented. If the legend is to be believed, the only reason hydroxychloroquine exists today is because somebody decided to go against received wisdom. In 1638, the go-to western treatment for malaria was blood-letting. Struck down with the disease in South America, the wife of the Spanish Viceroy of Peru supposedly took a punt on some tree bark given to her by an Incan herbalist. And so the European colonial elite discovered hydroxychloroquine’s mother drug.

Hope is an ever-present driving force in Quackery, a book that traces the history of miracle cures and asks why we’re so attracted to them. “There is a lot of power in the concept of hope behind something that feels like it could fix everything,” says one of its authors, Lydia Kang. A lot of the medics she writes about in her book truly believed in the cures they were peddling. “It’s just looking back that we realise it was a terrible idea.”

Medical history is full of heroes and villains, those whose gambles paid off, and those who harmed more people than they saved. Didier Raoult may be remembered as the prophet of hydroxychloroquine, or someone who encouraged the world to waste millions of dollars and many precious hours during the biggest global crisis since the Second World War. For now, we just don’t know.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox

SIGN UP

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts

SUBSCRIBE