“The discomfort that extroverts are feeling right now? That’s what introverts have been dealing with for as long as they’ve worked – especially those who have worked in open-office environments. Everything has been flipped on its head.”

So says Glen Cathey, a Florida-based keynote speaker who has spent the past three years educating business leaders about introverts in the workplace. I got in touch at the beginning of Lockdown Two in December, as hopes of returning to ‘normal’ office life in the UK were crushed yet again. For many, that news was bittersweet.

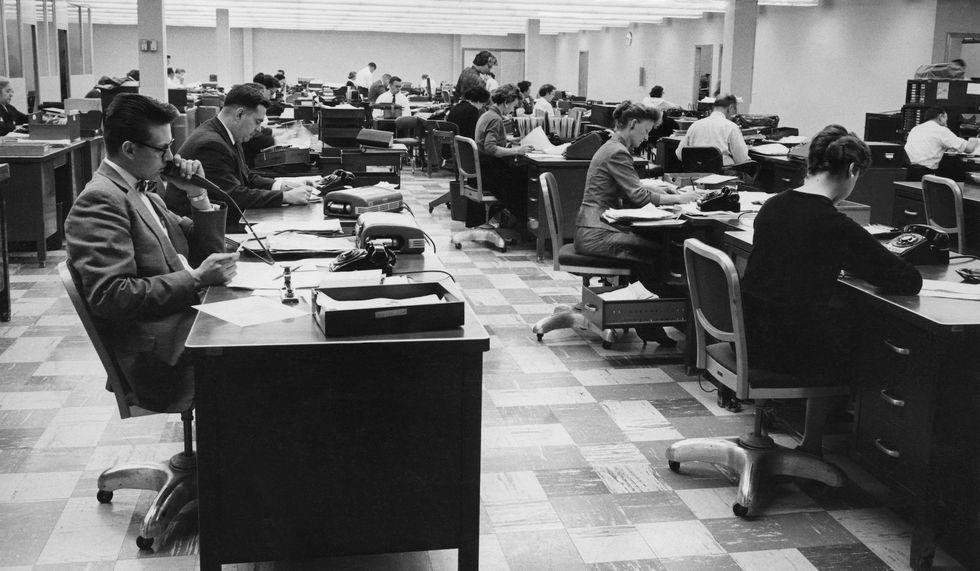

It is estimated that around one in three adults are ‘introverts’, a term coined by psychologist Carl Jung in the Twenties to describe people who feel physically and emotionally drained by social interaction. Often erroneously conflated with shyness, introverts are drawn to – and, importantly, gain energy from – isolation. Towards the opposite end of a wide spectrum you’ll find ‘extroverts’, who are driven by a desire to engage with other people; to voice their opinions and forge personal connections. They are, in some ways, the apex predator of the open-plan office.

“’Normal’ seems to be designed for extroverts over introverts,” says Cathey, who has long identified as the latter and has struggled in traditional working environments. “Most companies probably have a representative mix of introverts and extroverts, but there may be a disproportionate way they're heard and leveraged.”

That can manifest itself in being overpowered during meetings or frozen out of important decisions. An introvert’s failure to speak up or fulfil social obligations can often leave them feeling dismissed, and even bullied, by bosses and colleagues. So it’s understandable that many have relished the opportunity to build an office on their own terms during the pandemic, free of the paranoia and public pressures that once weighed them down. Lockdown life came with a mute button and the perfect get-out clause (“Pub? Argh I’d love to, but it’s illegal and they’re closed indefinitely”). What’s more, introverts were finally able to let their work speak for itself. Cathey tells me about one woman who contacted him at the beginning of the pandemic to talk about how happy she was to be working from home; how engaged she felt with her work, and how worried she was about the seemingly inevitable return to office. She’s not alone.

“I always wanted to work remotely, long before the pandemic, but I just never got [the] opportunity,” says Roberta*, who was laid off in the early days of lockdown and now works for an e-commerce shop in Scotland. “The perfect workplace is a place where I can be myself without feeling guilty that I don’t entertain my colleagues and I don’t feel constant pressure to be a chatty, smiling and crowd-pleasing woman.” In the past, she has heard colleagues refer to her as a “weirdo” and a “boring person” because she doesn’t want to socialise during or after work hours. “It was always said half-jokingly and I took no offence, but that’s the reality of it.” In 2003 Dr Marti Olson, author of The Introvert Advantage, found that 98 per cent of the subjects she interviewed felt they had been reproached and maligned for their social reticence.

On the Reddit forum /r/introverts, you’ll find thousands of users across the world bonded in fear over a future that too closely resembles the past.

Where kitchen catch-ups and post-work drinks can act as a much-needed respite for extroverts, Cathey says they represent the opposite for introverts. He tells me about a man he recently spoke to who, in pre-pandemic days, trekked far away from his office for lunch every day to ensure that no colleague would stumble upon him. “He thought that if they saw him out by himself, they might judge him. ‘Why didn't he come with us? Why is he going to eat at this place by himself?’” Cathey says that those unfair judgements could not only impact his standing in the office, but also his career prospects – an anxiety that Roberta identifies with. “I don’t know if being an introvert will impact my ability to succeed in this particular environment, but I am pretty sure I would be promoted quicker or get a salary increase sooner if I wasn’t an introvert,” she says. “I think my boss would have more confidence in me, but that’s because he judges personality more than skills.”

It’s a complex situation that Cathey blames on affinity bias, and he says preferential treatment for extroverts becomes particularly pronounced in the hiring process. “I think some companies miss out on fantastic hires because they didn't click, [but] you're not hiring somebody for how social they can be with you in an interview,” he tells me, pointing out that something as simple as eye contact – which introverts often struggle with – can cost you. “They think 'This is how I interact, and this introvert is not clicking with me. This feels kind of awkward'. It's hard to not have a negative, unconscious reaction to someone that's very different, or looks like they're not interested in chatting with you.” That bias is reflected in a survey of over 1,000 workers in the UK, conducted by Qualtrics in 2019, which found that 36 per cent of employees believed extroverts to be more naturally creative than their counterparts.

Once introverts are in the door, their ideas often get lost in the noise. The same survey revealed that over a quarter of introverts thought they were not provided with the chance to be heard by their companies, despite over 61 per cent believing they had ideas that would benefit the business. “Introverts often don’t like speaking or talking over people, so other people dominate the conversation,” says Cathey, who emphasises that it’s even harder for introverted women and people of colour to have their voices amplified. He thinks that remote video-calling apps like Zoom and Microsoft Teams have helped somewhat in that regard, as conversations can be moderated to a more inclusive standard, but he says that they still don’t necessarily address the fundamental differences in the way that these personality types form and express ideas.

“For a good 17 years of my career, I thought I was a slow thinker. I was very jealous of people that seemed to be able to process really quickly,” says Cathey, who eventually realised that he, like many other introverts, found it much easier and more effective to write down his ideas in an email to colleagues and bosses. It didn’t always go down well. “The response I'll get is, ‘Wow, that was a long email, why didn't you just pick up the phone?’ I don't want to annoy the extrovert, but it’s all about companies accommodating the different ways in which people communicate.” He says that “extroverts have a tendency to think while they talk”, whereas introverts mull over their ideas more.

In Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking, author Susan Cain presses home the cultural impact of companies side-lining introverts. “If we assume that quiet and loud people have roughly the same number of good (and bad) ideas, then we should worry if the louder and more forceful people always carry the day,” she writes. “This would mean that an awful lot of bad ideas prevail while good ones get squashed.” A lose-lose situation for all involved.

One thing’s for sure: we don’t know what a return to ‘normal’ will look like yet. Employees already had a legal right to request flexible working pre-pandemic, and British think-tank Demos has found that four-fifths of the population want to continue some version of remote working moving forward (though not necessarily from their desks). Compounded with the fact that many companies will be looking to shed costly office space in the near future, it seems inevitable that white-collar jobs will generally be more inclusive of introverts than they were pre-pandemic.

If you ask Cathey, the next steps are simple: just give people the time and space to think about and express ideas. That, and invest in the wellbeing of all employees. “Companies have to recognise that it's not just that they get better work done,” he tells me. “If they feel better, then they're more engaged. They’re happier.”

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts