For twenty years, I lived my life as the world is living it now – awash in Purell and anxiety. I don’t say this proudly. At the time, it wasn’t rational. It was a drain on my mental health and bank account.

But I couldn’t help it: I was a committed germaphobe.

This phase lasted most of my adult life. Finally, a couple of years ago, after a lot of work and cognitive behavioural therapy, I got over my germaphobia. I was free! What a relief!

And then the punchline: Along came COVID-19, and my germaphobia has come roaring back. My only solace is that, thanks to my years of microbial obsession, I have developed a better, wiser, more evidence-based version of germaphobia. Or so I tell myself.

To back up: I began my social distancing soon after college. When people stuck their hands out for a shake, I demurred, offering instead the now ubiquitous elbow bump. Or else I’d try to convince them to do a touch-free “air handshake,” which looks like two people having simultaneous tremors.

I boasted many other germaphobe bona fides. I washed my hands surgeon-style until they were raw. I didn’t clink wine glasses during a toast, unless it was the bottom of the glass, where the microbes were less likely to lurk. Before I allowed my kids to sit in the swings in Central Park, I slathered them with hand sanitisers, much to my wife’s dismay.

I got to be adept at balancing myself while standing on the subway – my version of surfing – since I couldn’t imagine allowing my skin to contact a subway pole.

I was so vocal about my fear of – actually, disgust with – microbes, the New York Post ran an article in 2000 about germaphobia, featuring photos of two prototypical germ haters: me and Donald Trump. (More on him later).

I’m not sure the origin of my germaphobia. My inborn OCD probably plays a part. I also did get colds and the flu with alarming ease, my immune system as welcoming as a Marriott, so I felt it smart to be extra vigilant.

I was also a huge consumer of germ porn, which couldn’t have helped. Perhaps you’re familiar with the genre: news segments that warn you that there are more germs on your remote control than on your toilet seat, your sponge is a hot zone, your cell phone should be quarantined. Cue footage of unwashed hands under black light, all Jackson Pollocked with glowing purple germ splotches.

That kind of thing.

I love the elaborate metaphors they use to convey the unimaginable number of germs. You have more germs in your gut right now than humans that ever lived on earth! (This is true.)

I contributed to the genre, in a way. I’m an author, and I worked my germ obsession into my books. For one book, I followed the rules of the Bible as strictly as possible. Because the Old Testament discourages touching women who are menstruating, I’d tell women I couldn’t shake their hands in case they were menstruating. This received mixed reactions. I also refused to shake men’s hands during my biblical year. The Bible says that men are unclean for a day after their “emission of seed.” So the possibility of a recent ejaculation gave me a good excuse not to touch male palms.

My wife hated the menstruation laws in particular, and my germaphobia in general.

Hated the smell of Purell – a romance-killer, she called it. She sided with the medical professionals (and there were many) who said my behaviour could actually backfire.

They’ve named their theory the hygiene hypothesis. The idea is that children in modern first-world countries aren’t exposed to enough germs, which throws off the development of the immune system. Our immune cells don’t get the chance to learn to recognise and assassinate the bad guys, thus our overly-sanitised world could paradoxically be responsible for the dramatic rise in allergies and asthma.

When one of our sons was a toddler, we bought him an ice cream cone on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. As he was walking out of the shop, his scoop fell on the sidewalk. Amazingly, he didn’t get upset. Instead, he got down on all fours and started licking it off the pavement. A woman walking behind him gasped, “Oh, my God.” But my wife? She had no problem with it. New York is one big dinner plate.

Over the past few years, I slowly migrated toward my wife’s way of seeing things. Germs took up less space in my brain. I became much more relaxed. I started shaking hands, even touching subway poles.

There were several reasons for my conversion.

First, I think the hygiene hypothesis has some validity.

Second, I felt my germaphobia was playing into the stereotype of a neurotic Jew. It’s a trope in pop culture – your Larry David, your Howie Mandell. I didn’t want to feed into that.

Third, I read a lot of rationalist literature about long-term threats, such as nuclear war, climate change, and artificial intelligence gone awry. I figured, if I’m going to worry about something, maybe those things are actually worth my anxiety, rather than catching a cold from a hotel sink.

Plus, I read some very convincing defences of germs. Turns out they suffer from bad PR. Our bodies are hosts to billions of germs, and many perform crucial life-saving functions. Only a small percentage are bad.

And finally, there was the Trump Factor.

I disagree with our president on almost every imaginable topic. It bothered me that we shared this one obsession with germs. Since very few of his positions seem based on evidence or rational thought, I figured maybe germaphobia was in the same bucket.

It inspired my re-examination of the topic.

I even found some evidence – and it’s admittedly far from proven – that germaphobia is linked to a heightened sense of purity, which can manifest itself in other unpleasant ways, such as fear of the other and fear of foreigners (Here’s a link to a New York Times op-ed by two scientists who argue that the more obsessed you are with germs, the more politically conservative you become. Again, I’m not totally convinced, but it’s an interesting theory).

So I committed myself to overcoming germaphobia. And I did.

Cut to last week, and the biggest epidemic since the 1918 Spanish Flu. We all became Howard Hughes, but with better reason.

In fact, if you are not a germaphobe now, you are irresponsible and endangering lives. (Oddly, Trump, the longtime germaphobe, seemed to get over his germaphobia. He repeatedly downplayed the Covid-19 threat, probably in an attempt to protect the economy).

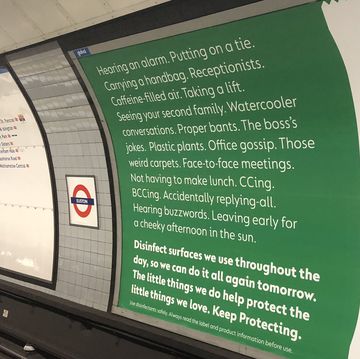

So now I’m back to washing my hands incessantly, not touching poles, opening doors with my elbows or a scarf-wrapped hand.

But maybe I’m also a bit wiser, having wrestled with this topic for decades.

Strangely, even though the stakes are higher, I feel my germaphobia is less anxiety-producing. It’s a calmer, more rational, more evidence-based avoidance of germs. I do all the best practices, but without that sense of disgust I used to have. Disgust is a draining emotion. I’m not a fan. I see it as a vestige of paleolithic times, and is dangerous and unreliable guide to morality.

I now try to take disgust out of the equation. I try not to fear or hate germs, because stressing about germs is probably counterproductive. Constant worry makes our immune systems more vulnerable.

So instead of ruminating all day about those little microscopic bastards with the ferocity of a recently spurned lover, I just avoid the hell out of them.

The information in this story is accurate as of the publication date. While we are attempting to keep our content as up-to-date as possible, the situation surrounding the coronavirus pandemic continues to develop rapidly, so it's possible that some information and recommendations may have changed since publishing. For any concerns and latest advice, visit the World Health Organisation. If you're in the UK, the National Health Service can also provide useful information and support, while US users can contact the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox