On a humid, cloudy day last May, on the leafy outskirts of Ghana's capital city, Accra, Roland Obeng opened one of his two Grindr accounts. Surrounded by wood-carved penises in his otherwise ordinary office, the healthcare manager set to work replying to messages in the LGBTQ+ dating app. Obeng – who identifies as gay and requested I change his name for safety reasons – works at the West Africa Aids Foundation-International Health Care Center (WAAF-IHCC). “I have two profiles,” he explained. “One of them is for my personal profile, and then one is for work – to help my community members to get tested.”

Obeng’s work profile, called Menz Corner, reads: “A good life starts with good health. Contact me for free HIV testing and STI screening with utmost confidentiality n lots of freebies,” and lists a phone number. Sometimes people write and ask how to use a condom; some send photos of their genital infections or want free flavoured condoms and lubricant. Others ask, “is the place discreet? Can I come?” Obeng said.

At first, many people have concerns about visiting the clinic, where Obeng works as a case manager, which nestles off the main road of a bustling residential area and is sheltered by palm trees. Public facilities in Ghana, Obeng explained, sometimes stigmatise or can be hostile to the LGBT community, and people don’t always feel safe exposing themselves in front of the general population. If the doctor can identify an infection and offer a prescription through social media, they will, but Obeng encourages his clients to come into the clinic to test for sexually transmitted infections and HIV. To assuage people’s fears, Obeng and other clinic workers and volunteers will personally accompany them.

Obeng, who is in his mid-30s, softly-spoken with warm eyes and a wide smile, said roughly five people per day reach out to him through Grindr. According to the clinic’s data, between October 2018 and May 2019, 48 clients visited through social media referrals. Of those, 23 (48 per cent) tested positive for HIV, which, in comparison to other outreach activities, is a very high yield.

LGBT people in Ghana face widespread discrimination and abuse — including mob or family violence, sexual abuse, extortion, and blackmail. Due to lack of economic and educational opportunities, some resort to sex work. “Stigmatisation and discrimination make it impossible for [LGBT] individuals to become productive members of the community when disclosure of their sexual orientation is likely to lead to them being thrown out of their jobs, schools, homes, and even their communities,” Phillip Alston, UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, said in a 2018 Human Rights Council report on Ghana. Nearly half of the discrimination cases filed since 2013 with the Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice were filed by LGBT people. Last year, the local press reported that a man who supported homosexuality and same-sex marriage had gone into hiding after his community in southern Ghana tried to kill him.

Before social media, gay men would meet up through word-of-mouth in what’s known as “hotspots” — clubs, food joints, or shops, where they can gather safely, and whose location changes frequently. Such meet-ups, though, are not without risk. Guro Sorensen, the head nurse at WAAF-IHCC, met someone recently who is gender fluid, whom I'll call Tomas. Tomas told Sorensen he’d spent time at a gay friend’s noodle shop, which had become a hotspot. One afternoon, in the light of day, Tomas went to the beach, where a group of men recognised him from the hotspot. “We know you are gay,” they told him. Then they attacked him.

Obeng and others at the clinic began to implement this social media-driven strategy in 2017 when they realised that large sectors of the population living on the margins of Ghanaian society — particularly LGBT people — are often the most vulnerable to HIV but remain hidden. “I am someone who uses Grindr a lot, and I was actually introducing a lot of people from Grindr and social media to this place, so we came up with such an approach,” Obeng said. “A lot of men who have sex with men come to social media because they want to be discreet, and people wouldn’t always want to show their face,” he said.

According to Dr Henry Nagai, who leads Ghana’s USAID Strengthening the Care Continuum Project, whose primary goal is to connect vulnerable populations with HIV services, social media has played a pivotal role in his team’s work, as well. “It helps you to be able to get into the network,” he said. “For example, the transgender community in Ghana is very small, hidden, discreet, and they have the highest transmission rate.” In the past seven months, Care Continuum’s digital health platform has had 98,972 interactions, through which they’ve received messages and offered referrals for services including HIV testing and STI treatment; nine per cent of all those who received HIV testing services in the program during this period were referred through social media platforms. “This is important because this percentage are those who are hidden and discreet and hard to reach through traditional outreach services,” Dr Nagai said.

Dr Naa Ashiley Vanderpuye-Donton, the director at the WAAF-IHCC clinic, shared a similar perspective. “It’s a very sensitive group because it’s criminalised in Ghana, and you can’t go about doing things openly," she said. “For them to come to us or for us to reach them, it’s complicated, and they’re not out in the open."

An archaic, colonial-era law – the Criminal Offences Act of 1960 – prohibiting and punishing “unnatural carnal knowledge” — interpreted as “penile penetration of anything other than the vagina” — criminalises same-sex activity in Ghana. While the law is seldom invoked to prosecute people, it can be used to arrest and extort people based on their real or imputed sexual orientation or gender identity. “Having a law on the books that criminalises adult consensual same-sex conduct contributes to a climate in which LGBT people are frequently victims of violence and discrimination,” Wendy Isaack, the author of a 2018 Human Rights Watch report, said at the time of its release. “Homophobic statements by local and national government officials, traditional elders, and senior religious leaders foment discrimination and in some cases, incite violence.”

The effect of the law, as well as the state’s failure to address violence and discrimination, the Human Rights Watch report found, effectively relegates LGBT Ghanaians to second-class citizens. The result is that those who exhibit health problems or HIV symptoms are afraid of the double stigma that will attach to them once they know their HIV status and disclose they are an LGBT person. “All of these factors are a complete disincentive to accessing health care and are detrimental for providing adequate care both to affected populations and to the population at large because it becomes a public health issue,” Graeme Reid, director of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Rights Program at Human Rights Watch, told me. Many, therefore, choose not to seek health care. And for a long time, Obeng was one of them.

Recent historical works suggest that pre-colonisation, dating back to at least the 16th century, many African societies were recorded as freely expressing a range of sexualities and gender relations — from male-to-male sex in Congo; transvestism in Ethiopia; and the men of the Nzima of Ghana traditionally marrying each other. But, beginning in the 19th century, the British Empire began its quest to conquer swaths of African territory, and in so doing, it imported Victorian laws, spread fundamentalist Christian values, and homophobia, intending to abolish “sodomy” and “savagery” in the region. These colonial-era penal codes and homophobic sentiments persist in Ghana and most former colonies.

“A lot of these laws were imposed on a kind of racist assumption of rampant sexuality. Like unbridled sexuality was taking place, including same-sex sexuality that needed to be regulated and controlled by the colonial authorities, so in a way, same-sex relations was seen as a sign of the primitive that needed to be regulated and controlled,” Reid of Human Rights Watch, whose organisation published a 2008 report about the proliferation and harm of such laws in former British colonies, told me. “Now, fast-forward 100 years, where embracing same-sex relations is seen as a kind of marker of modernity, and governments are pressured by former colonial powers – who imposed those laws in the first place – to repeal them, and they’re saying, ‘I don’t think so,’” Reid said.

In 1957, Ghana became the first sub-Saharan African nation to gain independence. Early in its independence, Ghana was crippled by famine, economic instability, and a series of military coups between the Sixties and early Eighties. But Ghana has held peaceful elections since 1992, and, in recent years, has been among the world’s fastest-growing economies. Ghana is the world’s second-largest producer of cocoa and Africa’s second-largest producer of gold; its expanding oil sector, since offshore deposits were discovered more than a decade ago, has also led to an economic uptick. But, according to Alston, the Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, Ghana’s inequality is at an all-time high; one person in five lives in poverty and one in eight lives in extreme poverty. While new infections of HIV have decreased significantly over the last two decades, sectors of the population – like men who have sex with men and female sex workers – remain disproportionately affected.

In June, Botswana’s High Court overturned sections of its colonial-era penal law, which criminalised homosexuality with up to seven years in prison. Judge Michael Leburu, one of the three ruling judges on the panel, said, “the anti-sodomy laws are a British import,” created “without the consultation of local peoples.” Leburu’s proclamation contrasts that of leaders in other former colonies in the region, where sodomy laws are said to reflect the country’s cultural values.

In April 2018, Theresa May said she “deeply regrets” Britain’s historical legacy of anti-gay laws across the Commonwealth and urged nations to repeal these “outdated” laws that criminalise more than 100 million lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans people throughout member countries. “Nobody should face persecution or discrimination because of who they are or who they love,” the former Prime Minister said in a speech at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting.

Today, homosexuality is illegal in 34 of Africa’s 54 countries, four of which employ the death penalty. Political and religious leaders and government officials across the continent, including in Ghana, regularly proclaim nocuous anti-LGBT sentiments. In June 2018, Kofi Tawiah, the head pastor of Osu Church of Christ, said, “homosexuality is considered as a capital offence which is abominable and is accompanied by capital punishment.” Professor Mike Oquaye, Ghana’s speaker of parliament, has called for harsher laws against same-sex conduct and conflated homosexuality with bestiality, while Moses Foh-Amoaning, a lawyer and lecturer at The Ghana School of Law, has announced plans to “cure” people of homosexuality with gay conversion therapy.

Ghana is a deeply religious society — predominantly Christian — and pastors sometimes preach that they’ve found a cure for HIV. Others, who adhere to Indigenous religions, which believe in the supernatural, may believe HIV infection is caused by curses and spirits and can be cured by herbal concoctions. Spiritual therapy from traditional priests, pastors, and healers is sometimes used as a substitution for antiretroviral therapy. Such beliefs present, “a major challenge to our work; it’s obvious that a pastor’s voice and a promised cure by herbalists sounds better in the ears of our clients than our lifelong treatment, unfortunately,” Sorenson told me.

Over the last 20 years, much of the LGBT-rights organising has been enabled and expanded through HIV and AIDS prevention activities, Reid explained. Programmes aimed at men who have sex with men have found a niche in which LGBT groups can push for their rights, while also recognising that “effective public health care can’t take place in an environment in which there are restrictive laws and negative social attitudes,” Reid said. “The two go hand-in-hand.”

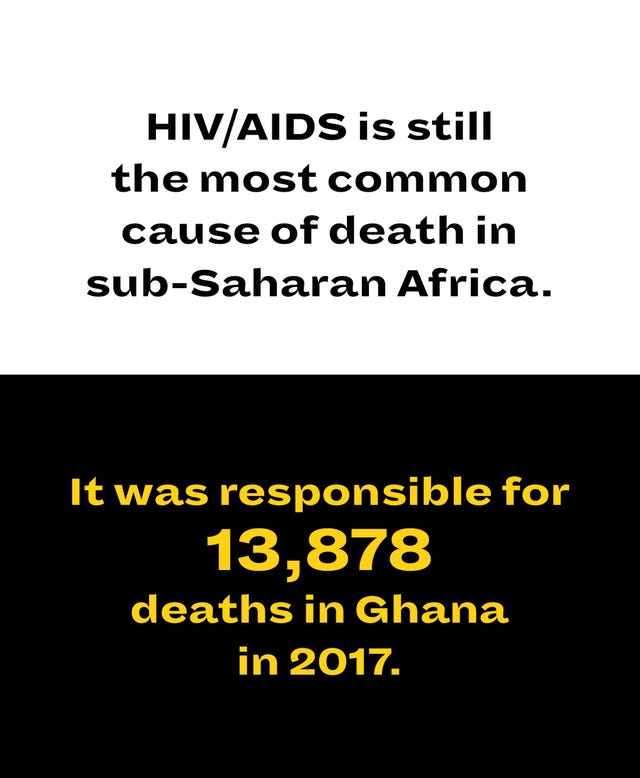

Ghana’s climate of homophobia has not only led to mob attacks, physical and sexual assault, and domestic violence but also health inequality. Compared with the prevalence of 1.3 per cent of HIV among the general population of Ghana, 18 per cent of men who have sex with men have HIV, but only 3.7 per cent are covered by antiretroviral therapy, according to UNAIDS figures. A 2019 study by the Local Burden of Disease Project at the Institute for Health Metrics found that, since 2000, HIV/AIDS is still the most common cause of death in sub-Saharan Africa and was responsible for 13,878 deaths in Ghana in 2017.

Recently, I spoke with Wisdom, the Executive Director of an LGBT rights organisation in Accra called Solace Initiative and the Executive Secretary of the Alliance for Equality and Diversity, who asked me to use his first name only. The situation on the ground in Ghana, according to Wisdom, is neither good nor bad: “I can say we are making progress in terms of attacks and abuses against gay men — we can go to the police station to seek redress,” he said. But, he said, “We still face stigma and discrimination when gay men access health services or health care”. Much of the HIV prevention and treatment programming has targeted men who have sex with men, “so there’s nothing targeted to bi women and lesbians,” he said, “who addresses trans needs?” He asked. “They are not part of the programming,” he said.

Sarah, the Executive Director of Courageous Sisters, an LBQT rights organisation, who asked only to use her first name, echoed the same sentiment. “As LBQ women, we’ve been left out of every health intervention,” she said. One of the challenges currently facing the community with whom Sarah works is corrective rape, forced marriages, and physical attacks. Still, often, those people do not seek help due to the stigma. “No health intervention or nothing is going on; we don’t know the HIV prevalence,” Sarah said. “There must be an implementation of HIV activities in Ghana targeting this population – if you don’t know your status, you don’t know what you’re doing,” she said. Courageous Sisters also uses social media to target marginalised women, using what Sarah called the snowball technique. Using Twitter, Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram, “we reach out to someone we know, and they help us get in touch with target populations, and it keeps going,” she said. “We let them know where you can go for health care and seek help.”

In the late Eighties, when AIDS was first discovered in Ghana, Obeng was a child. Even then, he knew who he was. He preferred to play with males and began to explore his sexuality as a teenager. “It was very natural, and I never learned it from anyone that this is how I should feel or anything,” Obeng said. But back then, he said, people in Ghana didn’t have the vocabulary to express what these sexual preferences and gender identities meant. It didn’t matter, though: Obeng knew that what he felt wasn’t accepted in Ghanaian society. People called him feminine names, and he understood that to survive, he had to be very discreet; Obeng didn’t invite his friends to his home, so as not to arouse suspicions in his community and family.

Growing up, Obeng described receiving a general education around HIV/AIDS but said, “we were not educated that HIV was really linked with men who have sex with other men or gay men,” he said. “Because I was aware of HIV as soon as it came to Ghana, if they had told us HIV was high among men who have sex with men, I would have been very careful. I didn’t know, so I was doing my thing as a man who has sex with men. I was having sex with my friends and hook-ups and all that,” he said.

Obeng’s life continued as usual until, eight years ago, he got a severe case of shingles that mercilessly spread across his body. He went to a public facility where a nurse suggested he get an HIV test. “Why should I go for HIV testing?” Obeng asked. “When she suggested it, I was a little scared because of my activities." The test came back positive, and Obeng now credits that moment with saving his life.

The problem, though, is that Obeng didn’t know where to turn at first: the public facilities in Ghana, he said, regularly stigmatise against gay men. Upon learning a person is LGBT, healthcare workers have been known to take out the bible and begin preaching, the implication being that such a lifestyle is a sin; doctors sometimes advise their gay patients who are HIV positive to discontinue having sex. “They are asked to stop basically being who they are,” Sorensen told me. Knowing this reality, Obeng didn’t feel safe disclosing his identity and status. Ghanaian society, in general, he said, “think it’s taboo, that we’ve been cursed and all that.” A friend soon introduced him to WAAF-IHCC, whose staff is trained to offer services to men who have sex with men. There, he received counselling and met a doctor who told him he needed to start antiretroviral medication.” The first time that I came here, I said, ‘OK, this is the place where I want to start.’ I had been to public places, but then this was different." The team of doctors and nurses there soon became a family to him, and he began working as a caseworker to reach other gay men.

Today, Obeng supports gay men to get HIV testing and regularly brings medication to several clients at their home or workplace; his role involves educating people on safe condom use and providing psychological support. “Someone might not even take his antiretroviral medication because he thinks that I’m taking the drugs to kill him – he believed this myth that they’re trying to take all the people living with HIV/AIDS away from the society by giving them drugs,” Obeng said. “Sometimes, you just have to use yourself as an example. I’ve been living with HIV, I’ve been taking my drugs for years, and I’m doing well, so why won’t you take yours?”

Still, Obeng has disclosed to no one in his family that he is gay or HIV positive. His mother, he said, constantly pressures him to marry. “I would love to let them know that this is who I am, but being in Ghana, and then the society does not accept that I come out, I just need to be discreet,” he said. “I’ve been living with this my whole life."

First-time visitors of the clinic, which is surrounded by homes in a developing suburb of Accra, sometimes mistake the clinic for a house and drive by it. Unlike the sterile environment typical of medical facilities, whether by design or accident, to many, the laughter and friendly chatter emitting from the facility makes this place feels like home. There, as the clinic buzzes with new patients, Obeng and his colleagues regularly gather to strategise about how to use social media most effectively to reach high-risk people. “It’s very difficult, especially in an environment where being LGBT is illegal,” Phinehas, a field officer, told me. The team has created a Facebook group, “Health Desk 4 Men,” through which people can ask questions and connect with the facility. “We use other platforms like Grindr, Blued, Romeo, Adam4Adam, and all other social media platforms that are mainly for gay men to link to the clinic,” Phinehas explained. One of Phinehas’s profiles, called ‘Men’s Corner’, says, “contact me for all your health needs,” and lists a number. Phinehas uses the apps to locate where people are publicly gathered, for instance, at a bar or the mall, and will try to engage them in person.

A peer educator at the facility, whom I’ll call Michael, randomly reaches out to people on dating apps when they are online. His Grindr profile contains a picture of a handsome man and lures people with the following description: “flavoured [condom] water base lube and lotion lube very effective for a sexual life,” and from there, the conversation starts. Michael also uses the location services on Grindr to locate high concentrations of people and tries to reach people in public spaces.

The approach, though, is not without risk. Recently, someone contacted Michael on Grindr expressing interest in the lube, expecting them to use it together. “There are some guys like that who will come and beat you up,” Michael said. “The person can send you fake pictures, and you can try to meet the person, and it’s not the real person you’re meeting, and there are some people there if you go to meet the person they can beat you, take your telephone, and take your money, and they can rape you. You have to be so careful, smart, professional, and intelligent." Some of the men he meets, or contacts, are anti-LGBT and spew insults or aim to cause physical harm. “The work, honestly, is not easy,” Michael told me. “There are people there who let me smile and let me be happy, and I try to focus on those people."

One day, in July 2017, a young man whom I’ll call James opened his Grindr app. A mutual friend had written him a message. “How are you doing, where do you live, let’s get to know each other,” the person said. The conversation was friendly and continued for a few days. The men exchanged numbers, and one evening James got a call from the man. “We were talking about what we do for fun, and he just asked me out of the blue, have I been tested before and do I know my status?” At first, James described being taken aback. “It’s not like we agreed to be in a relationship. I felt as if he was imposing. But he was my friend." The man on the other line continued: “It’s important to know your status,” he said.

“I’m afraid,” James told him. The man reassured him. He knew a friendly clinic in Accra. “There won’t be any stigma,” he said to James. At the time, James described having little education around HIV transmission. “People just meet, and then they just do it without protection,” he said. “Sometimes you ask, ‘have you been tested,’ and they lie—some don’t know if they have it or not. People are not really educated in that aspect. Only a few."

They agreed to meet the next morning at James’s home and go to the clinic together, where the man was a peer educator. “I was so nervous,” James said. “That was the first time I ever did any test, especially for HIV." A few years earlier, James had visited a public clinic where he tested positive for gonorrhoea. The doctors there told him to “bring the lady so they can test her,” he recalled. “I can’t even tell them it was a guy. If you have a partner, you can’t really go to the clinic together and get good advice; you have to shield yourself. It’s frustrating.”

When James arrived at the WAAF-IHCC clinic with the peer educator, who turned out to be one of Obeng’s colleagues, he recalled feeling shaky. Sorensen, the head nurse, tried to calm and reassure him. He began to open up about his identity. “I was so free and relaxed, and for a moment I didn’t feel like I was in Ghana,” he told me. “I didn’t know what the outcome would be." When the results came back positive, James said he wasn’t prepared. He told Sorensen, “I have to get my mind, my body, and my soul prepared for this.” James, who is now 25, began treatment in early 2018. “The first few days I started the treatment, it was hell,” he said. “I had symptoms and side-effects, and I couldn’t concentrate." Sorensen helped him through it and continues to check in on him.

James then decided that he no longer wanted to live a lie. He told his family he is gay. “They hated me at first and told me I should turn to God,” he said. “Now I’m alone and going to school,” he told me. As for his HIV status, he uses his experience to educate others. Stigma, he said, is still rampant: some people believe that “HIV is a virus through sharing of toilets,” he said. “It would be great one day if people in Ghana and Africa would stop the stigma and understand this is not so bad." In the meantime, he is waiting for the day when “two guys can go to a clinic and get tested together and just be free.”

This story was reported through a 2019 International Aids Society fellowship

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts