When Kevin Casey was laying oil pipes on the seabed in the 1970s, the problem wasn’t the sharks or the stingrays, it was the eels.

“Once, off the coast of Nigeria, I got to the end of a pipeline, which sat on a big half-shell guard,” he tells me one day at the Diving Museum in Gosport, Hampshire, where he now works as director. “I look in the half shell, and there’s this huge eel sitting in it. All I can really make out is its mouth. I don’t want to go near it but with diving, if you’re the man on the job, you’ve gotta get the job done, so I get the biggest crowbar we have, and I stand on the edge of the pipe and hit him in the head. He goes mad. There’s sand and silt everywhere. Eventually he turns back, but I had to wait till he leaves. And that’s when I saw how big he really was. If he’d got the liplock on me, I could’ve been a goner.”

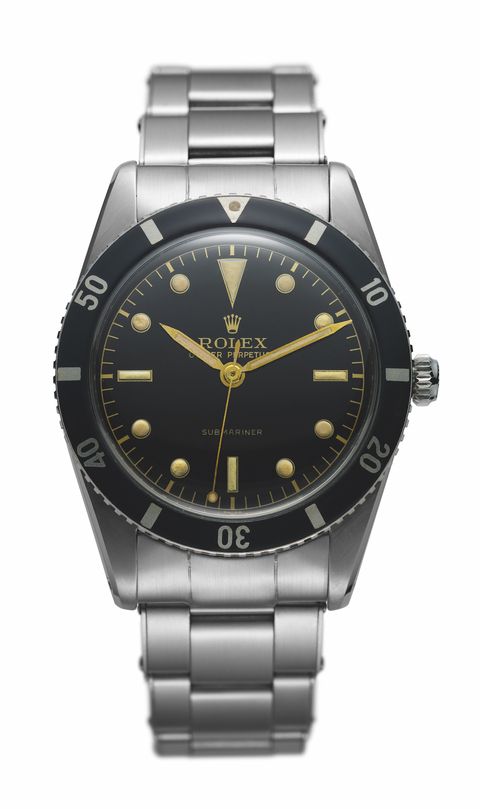

Casey worked as an oil-industry diver for 40 years, and he was a Rolex man. Still is. The watch he’s wearing is the first stainless-steel bezel Sea-Dweller Rolex made, he says: they made it for him when he convinced them that chemical reactions underwater could cause corrosion in the old metal-alloy version. He gives it to me to hold. The patina is beautiful and it weighs heavy in the palm.

“We were all Rolex guys in those days,” he says. “There weren’t many of us. The watches were how you recognised other divers. Still are.”

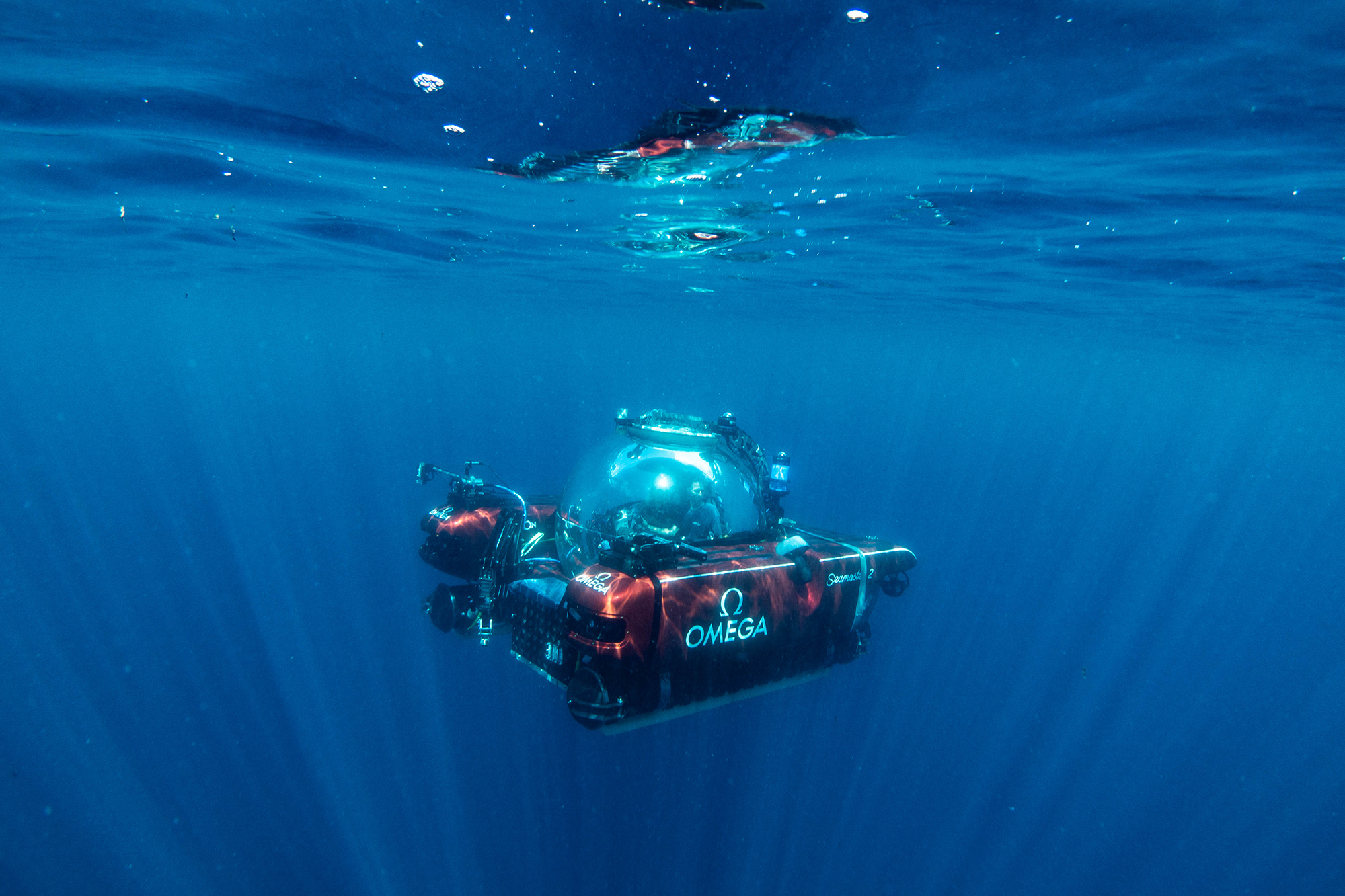

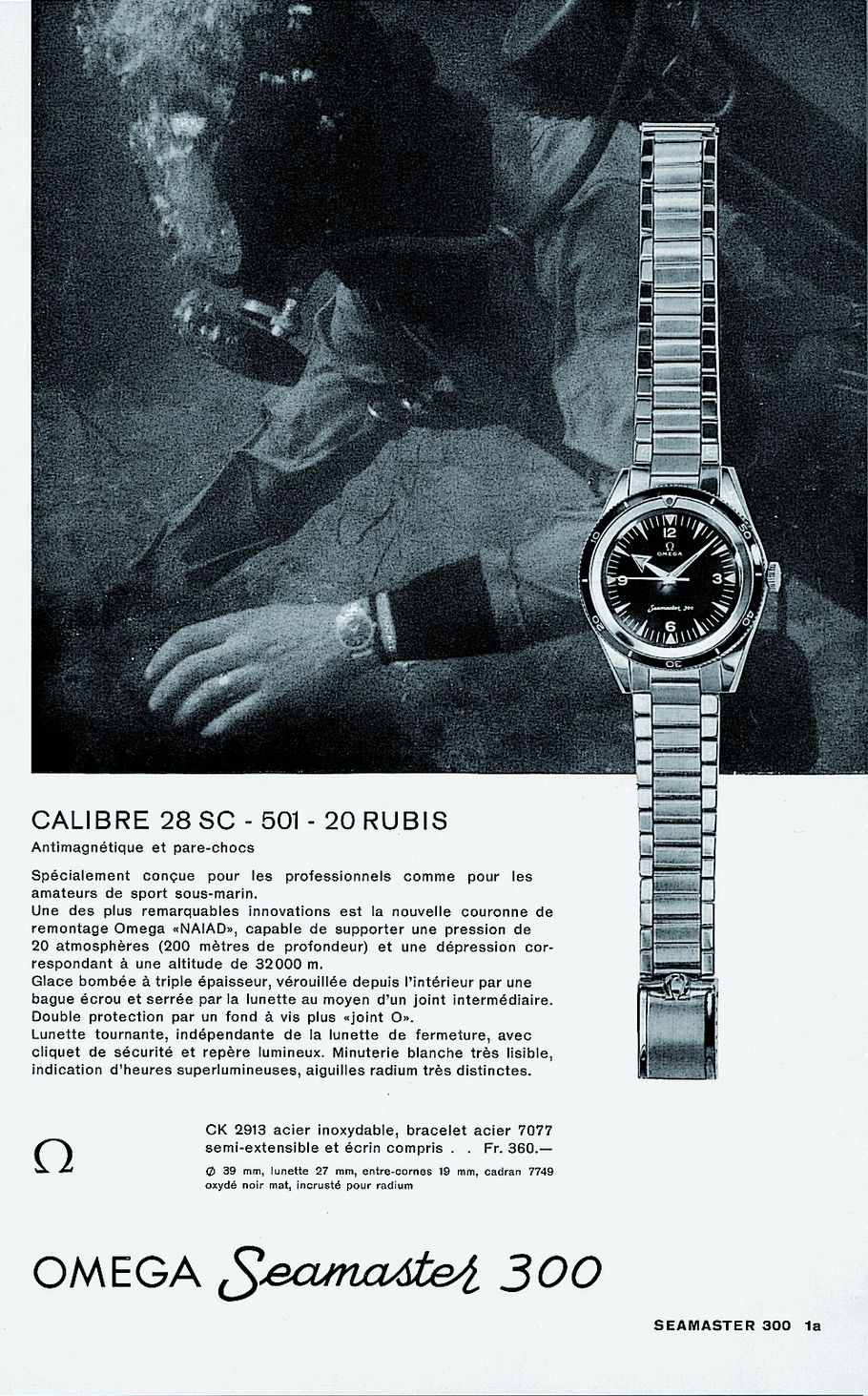

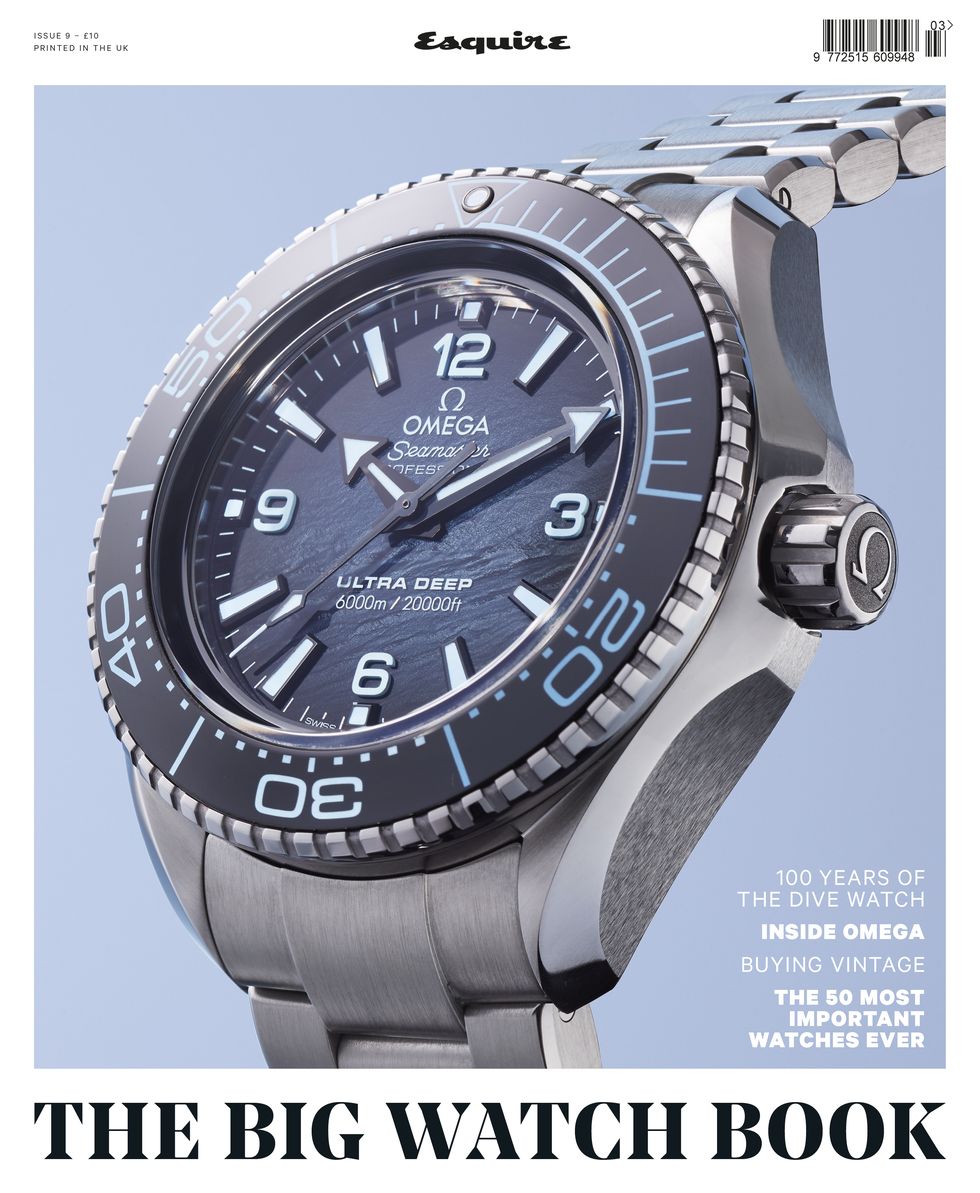

Is there any other watch category with quite the appeal and mystique of the dive watch? It’s certainly one of the best-selling categories and, while there are no official figures, anecdotal evidence suggests it’s the most popular of all. Most brands make at least one, and they’re seen as key to reviving a business. Consider what the Seamaster 300 has done for Omega since it became the Bond watch, or how the Black Bay boosted Tudor in 2012.

Of course, the success defies logic: their basic functions were long ago usurped by computers, and while they are marketed on the basis of their resistance at thousands of feet, the deepest any human has ever swum is 1090ft. There is also the historical aspect. No other machine has ever featured such small, perfect cogs and dials, or been crammed with so much of the crazy, brave and sometimes rather dark spirit that underlies human exploration and endeavour on Earth.

This year, the watchmaker Blancpain celebrated seven decades of its Fifty Fathoms. Along with Rolex’s Submariner (1954), it is often referred to as the first dive watch. But was it? If we take the dive watch’s USP as being able to survive the harsher conditions of the depths of the sea, then things become murkier. What about Omega’s Marine, with its waterproof double-latched case sealed with cork, which came out in 1932? Or Rolex’s orginal Oyster, “the wonder watch that defies the elements”, patented in 1926? All wrong, because their creators were not the first to come up with the concept.

In fact, purists point out, the dive watch’s origins date back over 100 years. And the idea wasn’t Swiss at all. Well, not entirely anyway.

The real story begins in 1918, with an Italian naval officer called Raffaele Rossetti. He had an idea for sinking ships: instead of firing missiles from a distance, why not get up close, where a miss became impossible? Why not get someone to sit on the missile and steer it? To this end, he developed a torpedo that could be piloted towards its target by two riders. But instead of them crashing into it, kamikaze-style, Rossetti decided they would attach magnetic mines and flee.

His torpedo did manage to sink an Austrian battleship, but the flaw was that the riders had no breathing gear and had to keep their heads above water, which meant they were inevitably spotted and captured. It took another 20 years for the Italian navy to add breathing apparatus so the torpedoes could be ridden underwater. The challenge for their pilot-divers was to know where they were, and if the mission was on time. To fix that, in 1935 the navy called on a supplier of gauges and instruments, one Giuseppe Panerai.

Mr Panerai bought in Rolex movements and built on them. He used Radiomir, a radium-based paint that glowed in the dark (it had the then-unknown drawback of being radioactive, and would soon be substituted). “It was military equipment, not a sophisticated watch,” explains Jean-Marc Pontroué, today’s Panerai CEO. “It was big because they needed to tell the time in the dark. Thirty metres deep, you can hardly see anything. That’s why we have big numbers, only two hands, no seconds, no complications, very water-resistant.”

That watch evolved into the Radiomir, which after World War II was supplied to the Italian special forces, and Panerai has supplied watches and other equipment to the Italian military ever since. It began selling to civilians only in 1993, and now supplies the Italian America’s Cup team and has links with diving clubs all along the Italian coast. The brand is famous for its fanatical followers, the Paneristi, who track and train-spot its obscure models. It’s true that Panerai has previously relied on other manufacturers, and does not have the same heritage in movements as some of its rivals, but its role in the history of diving is deserving of more recognition.

Certainly, reckons Pontroué, the undersea history partly explains the devotion of the Paneristi. “This community of people has been inspired by the military story and this historical diving. Those two elements are what brings them close to each other.”

Technically speaking, a dive watch is one that meets the International Standards Organisation’s 6425 rating. This sets out what makes a watch suitable for diving with breathing apparatus in depths of 100m (330ft) or more. The classic rotating bezel for measuring the duration of a dive (standard scuba dives generally last between 30 and 50 minutes) and other timing features are not included in ISO 6425, but are needed because diving involves complex, potentially fatal changes to the diver’s body that require time measurements to manage.

Simply speaking, the air we breathe is 21 per cent oxygen and 78 per cent nitrogen, and on land we don’t use the nitrogen as it passes straight through us. In a scuba cylinder, that air is compressed to 3,000lb per square inch, and the diver’s breathing equipment adjusts it to match the pressure of the water as they descend.

The problem is that as you go deeper, your body reacts differently to the gases. Oxygen becomes toxic. Nitrogen starts to make you feel drunk, and seeps into your muscles in bubble form. To get rid of those bubbles, you have to pause at certain depths and breathe the nitrogen out. If not, they will expand as you reach the surface, causing searing pain in the spine, joints and lungs — the reaction known as the bends.

The basic bezel is used with a depth gauge and tables that record the no-decompression limit for every depth. If you’re spending time at various depths, it becomes complicated, so the watch is important.

Until the 1940s, divers made do with waterproof watches and decompression tables, but when Jacques Cousteau and Emile Gagnan invented the Aqua-Lung in the mid-1940s, it became clear that something better was needed. The Aqua-Lung vastly improved on existing breathing apparatus, enabling divers to go deeper for longer — Cousteau, a French naval officer obsessed with the secrets of the sea, was driven to create it to give himself more time for filming.

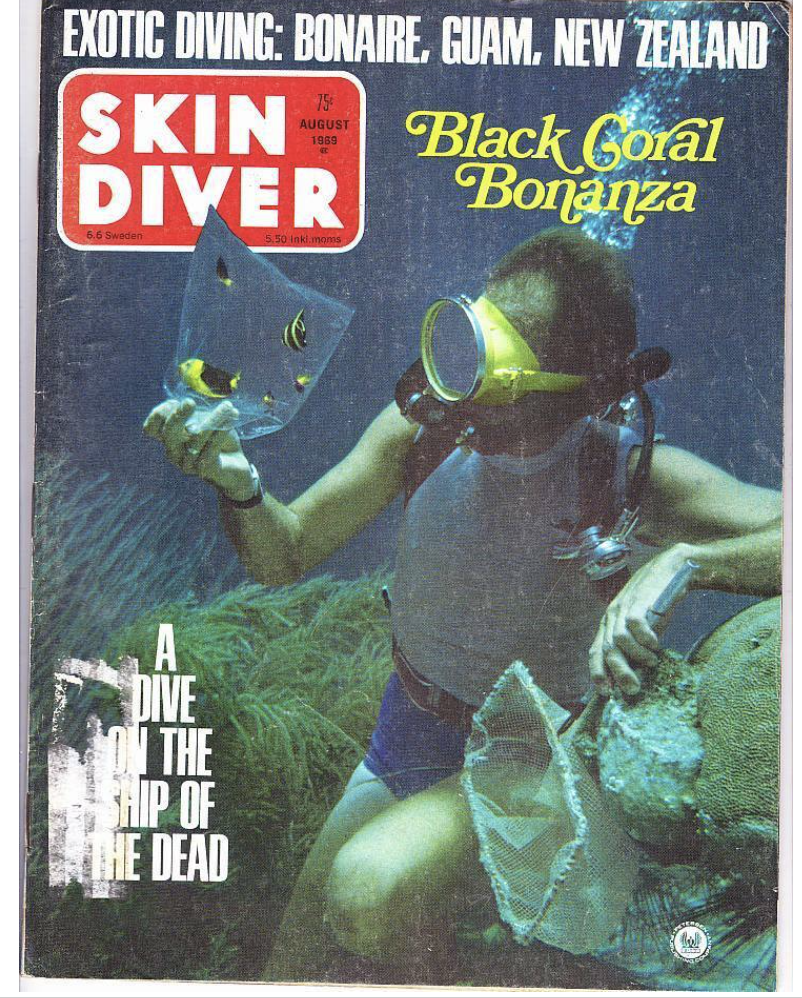

It went on sale in 1946 and together with the ready availability of wet suits and other diving gear from military-surplus stores after the war, it breathed life into what soon became a craze. When the forces gear began to run out, people reverted to “skin diving” and by 1951 they had their own magazine, Skin Diver, full of ads for diving gear and pictures of men posing with the fish and lobsters they’d killed with the pneumatic spear guns that had become wildly popular.

Skin Diver’s macho reporting often featured references to divers getting into trouble. “A 25-year-old diver was making $60 a day but was getting punchdrunk because some of the brain cells die due to starvation of oxygen,” runs the report on pearl diving in Tahiti in issue one. “I also saw how pearl divers die. Thou was a 30-year-old diver. He wouldn’t admit to himself he wasn’t good enough to dive 20 fathoms [37m]. His heart skipped a few beats and he passed out.”

Clearly, divers were struggling to keep track of time and their remaining oxygen supply. There was a gap in the market, and in this new battle for divers’ hearts and lungs, the first success went to a high-end watch company in Le Brassus, Switzerland.

Jean-Jacques Fiechter was a business exec who had thoroughly bought into the diving craze. Diving off the coast of France one day in the early 1950s, he ran out of air and had to ascend with no stops, risking the bends. By the time he got back to his day job as CEO of Blancpain watches, he had the idea for the first modern dive watch.

Blancpain’s early development work was accelerated by an urgent call from a French soldier. Bob Maloubier was a renowned maverick fighter who had been a secret agent for Winston Churchill in World War II. In 1952, France’s Ministry of Defence was putting together a unit of nageurs de combat, elite military frogmen who would swim into enemy territory undetected and plant explosives. Maloubier, stationed in Algeria, was their homme for the job. He immediately decided his crack team would need watches that would measure, among other things, their decompression times. After failing to find a manufacturer in France, he approached Blancpain, and the result, launched in 1953, was the beautifully minimal, monochrome Fifty Fathoms (a reference to the depth rating of 300 feet or 91.4 metres).

It is not clear whether Maloubier or Fiechter thought of taking the moveable bezel of pilots’ watches, and bezel watches such as the Rolex Submariner and the Zodiac Seawolf followed so rapidly that perhaps their makers had the idea at the same time. However, while the Submariner became the most iconic early dive watch, the Fifty Fathoms was the first modern diver’s watch to market, and caught the imagination of the new undersea explorers. It was worn by Cousteau and his divers in their famous documentary Le Monde du Silence, and by TV star Lloyd Bridges on the cover of Skin Diver. By 1958, it was standard issue for the US Navy SEALs and their combat divers.

The start of the golden age of diving — recreational, at least — is sometimes dated to a 1953 issue of National Geographic which featured a story about Cousteau’s underwater archaeology off Marseille. The story, it’s said, created huge demand for Aqua-Lungs and diving gear, and the other equipment that followed, notably underwater cameras.

Following the Fifty Fathoms, Submariner, Zodiac Sea Wolf and Omega Seamaster came a wave of lesser diving timepieces, many of which are now called skin-diver watches — basic and inexpensive, water-resistant to between 100 and 200m, and domed, with coin-edge bezels. By the end of the 1960s the style would be ubiquitous.

It was at this time that Rolex cannily worked on its reputation, presumably figuring that its customers would regard a watch that could work in deep seas as extra-reliable on land. It went for depth, even though seasoned divers themselves can be withering about those newbies who ask how deep you’ve been (“Can’t see much below 30ft anyway,” notes Casey). In 1960, when Swiss oceanographer Jacques Piccard and US Navy lieutenant Don Walsh piloted a bathyscaphe to the bottom of the Mariana Trench, it had an experimental Rolex watch, the Deep Sea Special, attached to the exterior; it was, of course, the greatest depth to which any watch had ever gone. At the same time, Submariners were being bedded into the culture: they were the watch worn by Sean Connery in the first 10 Bond films.

Thunderball (1965), with its incredible speargun fight sequence, became the high-water mark for subaquatic movies, but undersea adventures were everywhere, a reference for the bold scientific advances of the 1960s (Operation Petticoat, Thunderbirds, Ice Station Zebra) and even the experiments in consciousness. Cousteau’s films showed shifts in colour (water absorbs red and orange, so the naked eye translates them into blues and greens), and it is tempting to make a link to the psychedelia of the mid-1960s. When John Lennon took LSD for the first time in 1965, he mistook George Harrison’s bungalow for a giant sub, an image that may have led to the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine. True, Paul says he got the idea on holiday in Greece, but then how to explain “Octopus’s Garden”?

Casey, not a man given to flights of fancy, says the link might not be as mad as it sounds. “You see some amazing things, and you’re definitely aware of being in a completely alien environment. I remember once walking on a sea bed just as we were about to start drilling,” he says. “And I thought, I’m walking where no man has ever walked before, and I wish other people could see what I could see.”

Casey and his colleagues could spend so long at the bottom of the sea because of saturation diving, a new technique that arrived in the mid-1960s and is strongly associated with Britain’s 1970s oil boom.

Saturation divers are hardcore. Essentially, they don’t decompress when they’re working, but remain in pressurised living quarters until they finish a job. They also use experimental mixtures of gases, which in the late 60s and early 70s not infrequently killed people. There wasn’t much testing, Casey remembers. “They needed the oil out, because there was an energy crisis. So basically, you said you could dive, and you were working as a diver; I went straight off working on boats servicing the rigs. You stayed clean and you got paid more.”

Sat divers needed more robust watches with greater capabilities, and so, from the late 1960s, watch companies had to consider needs beyond waterproofing and timing. In this era, for example, some brands began to add escape valves to release the helium that built up at depth.

Casey wore his Sea-Dweller almost to the end of his career, even when the dive computers appeared in the 80s. “The dive watches weren’t like that other stuff [all other fancy watches] to us. I mean, they weren’t expensive like they are now; they cost a few hundred quid, and we were very well paid. If you had some spare time, or you got a bonus, blokes would just say, ‘I’m just off to get myself a new Rolex’, and nip down to the jewellers. When I realised how valuable they’d become, I was shocked. I also stopped wearing it in the water.”

Muscled up with new features and tougher cases, other dive watches of the late 1960s and 1970s became chunkier and more complicated. Many have become cult watches: the 1968 Doxa Sub 300T, the 1975 Seiko “Tuna” (so nicknamed because its size evoked a tuna can), Omega’s “Elephant” Marine Chronometer. They looked like physical incarnations of the increasingly macho sea movies of the period: Spielberg’s Jaws (featuring Richard Dreyfuss in an Alsta), Peter Yates’ Deep (Nick Nolte in a Submariner; Robert Shaw in a Seiko 6217).

The ultimate 70s beast was surely Omega’s giant Plongeur Professional, or Ploprof Seamaster, a wrist-buckling steel monster that was the triple concept album, or six-inch stack heel, of dive watches. Omega lavished time and money on it, only to find it didn’t really sell. “It was just too expensive,” says Roger Ruegger, editor of WatchTime. “No matter how many pieces they would have sold, they could have not have made up for the time and money they invested. But it has been a cult watch ever since. For hardcore divers, it became an iconic piece when it was launched. A lot of divers in historical diving societies still wear their vintage Ploprofs to dive. They like to remember.”

In the early 1980s, three divers in Pennsylvania set up a company called Orca. It was one of several new businesses making wearable dive computers, which used algorithms to calculate tissue-gas loadings and “safe-ascent depths”, and in 1983 they won the race to bring a model to market. The Orca Edge was expensive at $675, and not perfect, but its ongoing, real-time displays did allow experienced divers to make good estimates of what they needed to do to decompress.

Dive computers were not the only thing to see off the glory days of the dive watch. The quartz revolution and rise of the digital display undermined mechanical watchmakers and made the rotating bezel look obsolete. True, there were still popular and impressive new models (the IWC Ocean 2000; the Tag Heuer 1000), but by the end of the 1980s the dive watch looked as out of time as prog rock.

The revival is sometimes dated to 1995 and the impact of the Seamaster 300 in GoldenEye, but Ruegger knows otherwise. He grew up in Switzerland during the Swatch boom of the late 1980s and 90s, and recalls people queueing for the 1990s Swatch Scuba. The Scuba was water-resistant to 200m, but of course, in the postmodern Swatch way, was really all about the look; it seems doubtful anyone bought it for actual diving. It was followed by the Bora Bora, Barrier Reef, Hypocampus, Medusa, Blue Moon and best-known, 1991’s Happy Fish.

“These Swatches in particular had people camping in front of stores, like certain smartphones do today,” Ruegger remembers. “They were key to the renaissance of the dive watch because they got people used to the idea of wearing a dive model as an everyday watch.”

This may also have been helped by a reaction against 80s slickness, and the resurgence of 70s styling in the 90s. By the mid-90s, Omega was selling 50,000 Seamaster 300s a year. In 1993, Panerai relaunched with the Radiomir front and centre, then Blancpain reintroduced the Fifty Fathoms and IWC brought back the Aquatimer. There were more: in 2002, Breitling launched the first mechanical dive watch water-resistant to 3,000m; there was the G-Shock Frogman, Seiko SKX and the IWC Deep One, which updated dive tech by adding a depth gauge. Good-looking, easy to understand and with backstories, they were key to reviving interest in the whole Swiss watch industry.

It’s true there was a darker side of that period. What seemed at the time to be exciting boundary-pushing now looks like irresponsible madness. The sharkskin straps; the treatment of the ocean as a playground for rich men; the sponsoring of dangerous record attempts in which divers died. The diving-watch revival also brought back some of the attitudes of the 1950s, and the best we can say is that lessons have been learned. “Such things do not happen now,” says Ruegger.

Diving watches (Sinn’s U1, Richard Mille’s Tourbillon Chronograph) still innovate, but these days the focus has switched to ecology. Divers conserve and connect with the natural world; manufacturers invest to protect the ocean. Blancpain’s work in this respect is outstanding, notes Ruegger, and it has rightly boosted the rep of the Fifty Fathoms. Dive watches are so well-known now there aren’t really any obscure models left to discover; instead, it is more interesting to look at the efforts of manufacturers to do good.

Gavin Hulmston, a project manager in the energy industry and owner of a YouTube channel called Nomad Dive Logs, embodies the new spirit. He is a technical diver: he uses unusual gas mixes and studies decompression techniques so he can go deeper and remain underwater for longer. This isn’t for bragging purposes, it’s to get the feeling of being in unexplored places, the peace of being alone and far, far away. When he talks me through his stunning, high-definition videos of his trips to hard-to-reach shipwrecks and caves around the world, I am reminded of the diver-as-consciousness-explorer idea.

“Diving for me is the opportunity to experience places that very, very few people can visit, and to interact with marine life and historical artefacts that will never be seen in that state on land. And you can be at peace; it doesn’t get any quieter than it is down there, and if you turn off your torch, there is nothing. It’s just black.

“People will tell you there is a peace, ease and tranquillity that you only know under the sea. It’s a privilege to go to those places.”

Back at the museum in Gosport, Kevin Casey looks at the sun glinting on the Solent and tells me about a time when they had a problem with a pipeline in New Zealand, and he had to dive down to photograph it. He was putting down markers when he suddenly felt something tugging at the camera, and he looked down to see that an octopus had got hold of it. It was trying very hard to drag the camera under its rock.

“They did like shiny things, you see,” he says. “But the camera was attached to my suit, so he was taking me with him. I’m afraid I had to fight him for it. I won.” No octopus ever dared try for the Rolex, he says.

I ask him if he misses it all now he’s retired. “I don’t miss getting up for work,” he says. “But the diving… hell yeah. Every time I look at the water, I think about it.”

He mimes falling backwards to go under, and smiles