The American mechanical engineer, science communicator and television presenter has built a sundial for the Mars Exploration Rover, advised president Obama on climate change and voiced himself on Scooby Doo. But does he know if time exists?

Let’s start with a seemingly easy question I saw put to you on your website: Does time exist?

Like, dude, like, whoa! As far as I’m concerned, time exists. The frustrating thing about being alive, man, is one day you’re going to be dead. It’s awful. But, as the saying goes, we are all time travellers, but we’re only going one way. Why are we only going one way? That’s a remarkable, deep question.

Does time as we understand it exist in space?

Well, if you don’t think it exists, can I have your car or your worldly possessions? Because you might as well just die right now.

What I mean is, does time exist in deep space as it exists on this planet?

Oh, so, that’s a great question! The premise of the bit — as we say in comedy writing — in science is that the universe is knowable. As near as we can tell, the laws

of physics here on Earth apply everywhere in the universe. If they don’t, that will be of great interest and it is our quest — in science, in cosmology, in astrophysics, in philosophy — to understand why it wouldn’t be the same here as it is out there. Once you start thinking about the nature of time, it really affects every thought that enters your mind.

Can we agree that time is a dimension?

Oh, yeah. It’s the fourth dimension. You know what? I worked at Boeing. I like to remind people, if you’re ever on a 747 aeroplane, don’t worry — I was very well supervised. Anyway, we had four-dimensional autopilots even in the 1970s. So the pilot put in wherever he or she wanted to go, which would be an airport that will have a latitude, a longitude and an altitude above sea level — that’s very important. When you’re going to land in Nepal, you’ve got to take into account how high you are above sea level, let alone if you’re going to some exotic place like Denver, Colorado. Then, the other thing is, you put in what time you want to get there. So yes, we have four dimensions everybody: x, y, z and t. And the world goes round on account of it.

Is time a subject where the lines between science and philosophy can get a bit blurred?

That’s part of its magical quality. Our perception of the passage of time versus our ability to measure it is really… I want to say always in conflict, but it’s something that has to be reckoned with in the traditional sense of the word “reckon”. And, you know,

I spent quite a bit of time with sundials. My dad was a prisoner of war in World War II for almost four years. The Japanese military confiscated all his jewellery and watches, so he became very interested in using the sun to keep time. I grew up with all this sundials stuff in the background. My father wrote a book about sundials. I took a lot of pictures of sundials, talked about sundials. When you go to reckon time using the apparent motion of the sun and the Earth’s sky, it gets tricky pretty quickly. Days are longer in the summer than they are in the winter, and the moment the sun is highest in the sky — the so-called solar noon — varies by as much as 31 minutes over a year.

Isn’t gnomonics the correct word for the study of sundials?

Gnomonics, yeah, that’s a good word. The gnomon is the object that casts the shadow on a sundial. I take it for some reason you’re not a member of the North American Sundial Society?

I’m afraid not.

I encourage you to join, especially if you own seven or eight pairs of Birkenstocks. You’ll fit right in.

How important to humankind was the invention of mechanical timepieces?

Well, you know what we like to say, the invention of a clock — the clock — is much more significant, historically, than inventing a wheel. If you’re a people living [in a place] where trees fall over, then inventing a wheel is not that hard. It happened in a lot of places because if you’ve got trees falling over, you can put stuff on top of them and they’ll roll — from there, you can work your way to a wheel. But getting a clock to reckon time is a lot more complicated. By the way, our clocks turn clockwise because the shadows of sundials in the northern hemisphere go clockwise. Ninety per cent of the people in the world live north of the equator and most of the land on Earth is also situated north of the equator — that’s just how it shook out here. And so, understanding that shadows fall a certain way because the earth is a ball, is just one of the amazing things you need to know to make a mechanical clock.

You’re CEO of the Planetary Society — what’s the aim of that organisation?

Our mission is to advance space science and exploration, so the citizens of Earth will know the cosmos and our place within it, since you asked.

Would you rather travel forward in time 100 years and see where we are or visit the Moon?

I’d go forward 100 years. Right now, I’d prefer not to go forward, say, 30 years. What’s going to happen in the 2070s or so, the human population is going to start to go down and I think then there’ll be more resources for each person. In 100 years, I think we — humankind — will have harnessed fusion on Earth’s surface and also have solved some big problems. Visiting the Moon, I think, will be pretty do-able in the next 30 years. If I had a chance to go I would, but only with the stipulation that I get to come back.

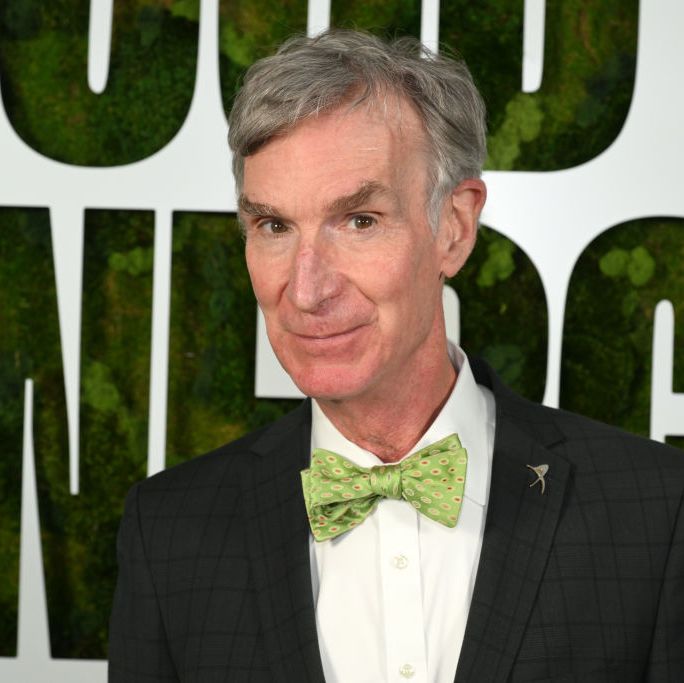

Do you wear bow-ties all the time for reasons of style or practicality?

Both. Bow-ties are very practical. In the laboratory, they do not flop into your flask. I can’t go back to straight ties. I tried it a few times. You’re wearing a bib, OK? When you’re dressed up, you wear a bow-tie, that’s all I’m saying.

How do you feel about the clip-on?

No. I can’t. People, what would they say if I was running around in a clip-on bow-tie? I shudder to think.