Inside a workshop in Garland, in northern Texas, one of the great problems of watchmaking was being pored over by an engineer named George H Thiess. It was the late 1960s, a period dominated by the space race and visions of steel and glass and neon-hued utopia, of flying cars, dinner in a pill and great technological leaps.

Meanwhile, over 1,400 miles away in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, John M Bergey, the head of research and development at the Hamilton Watch Company, an American watchmaking powerhouse, was trying to solve the same issue. But he and his crack team of engineers had hit a wall. How, Bergey asked, can you shrink a digital clock down to the size of a wristwatch?

For years, watch manufacturers and the engineers employed by them had wanted to stamp their name on the future of the craft, to create a watch with unparalleled accuracy, clarity and futuristic performance. Analogue watches had existed for centuries and the digital clock, with digits rather than hands, since 1956. Hamilton had made the world’s first electric watch with a traditional dial and hands in 1957, the Hamilton Electric 500. But the next leap, digits on your wrist powered by solid-state computer tech, in which there are no moving parts, was yet to be perfected.

Japan’s leading watchmakers Seiko as well as the Swiss had already made headlines with their electronic quartz watches. Also, Hamilton was losing money, it was down $24m in 1970 alone, so it was desperate to prove to the world that it was a serious and future-facing player in the quartz world. It hoped a bold new product, to be named Pulsar, would jump-start the business. It also wanted to capitalise on the space exploration angle, then the hottest topic of conversation. Part of the Pulsar marketing was that it was “as silent as space” with no ticking.

Soon the two companies would join forces: Thiess, the Texan engineer, and his company Electro/Data would provide the watch’s internal technology; Hamilton would supply the red and blue might. Soon, in 1970, they had a prototype and by 1972 they had released the first generation of the Hamilton Pulsar to the public, a digital watch named after a rotating neutron star that emits bright magnetic beams of light.

It was an instant hit.

It was film director Stanley Kubrick who helped inspire the first digital watch. In 1966, he approached Hamilton with a proposition. His next film was to be an epic science fiction picture titled 2001: A Space Odyssey. IBM, then the world’s largest computing company, had been approached for drawings and blueprints that could imagine the future of personal computing, designs that would go on to influence HAL 9000, the film’s artificial intelligence character. Aerospace engineers — not prop makers — designed panels, displays and devices for the spacecraft interiors. So when it came to conjuring up a wall clock from the future, something digital, it made sense to approach the country’s greatest watch manufacturer.

The result was a sort of squashed plastic sphere running on Nixie tubes — glass tubes with wire filaments shaped like numbers stacked behind one another — filled with neon gas and powered by electricity. Hamilton also came up with a space-age watch, though this was analogue. The Hamilton X 01 was an out-there looking steel cuff that appeared on the wrist of Gary Lockwood’s character Frank Poole, for about 20 seconds. The Nixie tube clock, however, ended up on the cutting room floor.

Not that John M Bergey and co-creator Richard S Walton minded too much. The pair had previously worked together in Hamilton’s Military Division, one of the company’s sub-departments, where they collaborated on a timed fuse. Now they were inspired anew. If they could make a digital clock that looked like the future, why not a digital watch? All they lacked were the resources. Which is where George H Thiess, Electro/Data and its solid-state technology came in.

The biggest problem was that, in 1969, there was no blueprint for a watch using computer technology. For mechanical watches there was centuries of know-how to reference, but creating a truly digital watch, with no hands, was a step into the dark. Digital alarm clocks had existed since the Fifties, but these were plugged in to the mains and were not designed to be worn to function.

“It was the first watch of its kind,” Houston Rogers, a Hamilton employee from 1967 until 2004, explains. “The LED technology was from Nasa. No one else had it.”

The battery system alone was hugely complicated. To create a watch that didn’t deplete immediately meant that it could only show the time when you pressed a button, and then for just one second — a problem that would have resonated with engineers on the Apple Watch 40 years later, its “Always-On” display only arriving with the fifth iteration, 2019’s Series 5. (Apple snarks love to point out that mechanical watches have come with “always on” displays for centuries.) During early press junkets for the new Hamilton watch, Bergey had to hide it from journalists’ view while he quickly swapped batteries.

Also, it wasn’t really a watch at all.

Hamilton and Electro/Data had to essentially create a solid-state computer that could fit inside a watch casing. There may have been no moving parts but there were 3,474 transistors. If one piece eroded or fell out of place it could be game over. At this stage of development, the Pulsar couldn’t yet be mass produced so everything had to be placed by hand.

America was introduced to the Pulsar “Time Computer” on 5 May 1970, unveiled on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, one of the nation’s most watched talk shows with an audience of up to nine million people. Housed in a futuristic cushioned case, the Pulsar was made from 18k gold down to the bracelet. Under the hood were seven ceramic circuit boards, each made from scratch, fused and soldered together by hand by Hamilton’s engineers.

The time-keeping element was powered by a quartz crystal, while the watch itself ran on a rechargeable, three-cell, 4.5-volt battery. There were no hands, instead it featured an LED “time screen” made of synthetic ruby with 27 diodes in each digit that displayed the time for 1.25 seconds when the wearer pushed a button on the front. Hold the button down for longer and the hours and minutes would be replaced by seconds. A unique photo sensor continuously monitored the ambient light and adjusted the

display brightness accordingly. It looked like something straight out of science fiction. Perfect.

“The machine finally put Mickey Mouse out of work,” said Carson, after demonstrating the time and date functions to camera. “That’s weird, isn’t it?” He then revealed the price: “This will sell for… I guess we can mention this, right? It will be available for consumers next year [and] will sell for $1,500.”

Ed McMahon, Carson’s sidekick and announcer, seated to his right, let out a shocked whistle, setting up the next line.

“The watch also will tell you the exactly moment that you went bankrupt,” said Carson, and the audience fell about.

While Bergey, then 36 years old, might have had reason to feel despondent over his masterpiece being mocked on national television, the American public were transfixed: The New York Times called it a “space-age wrist computer” and that it was “a new era in the science of measuring time”. One watch expert called the digital display “the greatest technological leap since the hairspring in 1675”.

“While Johnny didn’t seem too impressed, the rest of the country was,” says Hamilton’s Houston Rogers. “No one in the industry had seen anything like it and they were all interested in acquiring the technology for them to use on their own products.”

In April 1972, the first generation of Pulsar finally went on sale to the public, with improvements made to the quality of the LED display and the module inside the watch. The 18k gold version retailed for $2,100 — more than a top of the range Rolex at the time — and was limited to 400 units at fancy retailers like Tiffany’s and Neiman Marcus. That first production run sold out in 72 hours.

“We, as employees, were excited and proud to be working on the Pulsar. Customers were excited about it,” says Rogers, who still wears his Pulsar to this day. “When I wore the watch in public, it always drew crowds with people looking at the watch and stating how cool it was. The watch just sold itself and if people could afford it, they would go out and buy one.”

The P2, an improved version supported by a larger production run, was released in 1973. At $395 (more than $2,300 today), the stainless steel base model improved on price, but was still more expensive than as many new cars at the time. It featured a more rounded shape, a mineral crystal face and improved performance. Most importantly, it retained the sci-fi aesthetic of its predecessor.

Indeed, this was a watch that had comprehensively done away with all the irksome elements of boring, traditional timepieces. As a Pulsar promotional film stated at the time: “The ultimate in reliability — no moving parts. No balance wheel, gears, motors, springs, tuning forks, hands, stems or knobs to wind up, run down or wear out!”

Celebrities flocked to buy it: Elvis Presley, Joe Frazier, Keith Richards, Elton John, Jack Nicholson, Gianni Agnelli, the Shah of Iran, Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia and Peter Sellers were all fans and wearers. President Richard Nixon was rumoured to have been bought one by his daughter as a Christmas present. Roger Moore as James Bond wore a P2 in Live and Let Die.

“It was a watch worn by the influencers of the time!” says Hamilton CEO Vivian Stauffer today. As one article stated, “If you didn’t have a Pulsar P2, you were a nobody.”

Bergey had been vindicated for his pursuit of digital. At its peak, tens of thousands of Pulsars were being sold a month — more than any other watch at the time. It had also become the first American watch to be imported into Switzerland, a monumental achievement. In an article posted to the State Library of Pennsylvania, Bergey recalls visiting Tiffany’s in New York to observe the public reception of his creation. “The Pulsar showcase was a hub of activity,” he recalls. “Customers would sidle up to the counter, pluck down a wad of money and point to the Pulsar of their choice as casually as if they were buying a jelly doughnut.”

Despite this success, and despite “the ultimate in reliability” claim, there were technical issues with both the first and second generations of the watch. Batteries failed and the computer module supplied by Electro/Data was faulty in some watches, resulting in a recall. “People would sleep wearing their watches and the LED would be pressed so the light would be on all night and the battery would die,” says Rogers. “It was also hard to see in the sun, so the LEDs were made brighter. Also, the butterfly back would fall off due to a corroded battery.”

This didn’t detract from sales or popularity, though. Scores of new models were added into the Pulsar family as the 1970s wore on: sports and female-focused versions and special luxury editions imprinted with Tiffany’s logo. By 1975, Pulsar had grown into a $25m a year business with sales figures of 150,000 LED watches annually. The Hamilton company created a subsidiary, Time Computer Inc, solely to manufacture and market its runaway hit. The apotheosis came in December that year, when an 18k gold calculator version priced at $3,950 (about $19,000 today) was released, making it the world’s first calculator watch. (“The calculator on your wrist is also a watch,” announced the adverts.) US President Gerald Ford told reporters he was hoping to receive one from his wife that Christmas. When reporters then informed Betty Ford of his wish — and its cost, $3,950 — she graciously suggested otherwise. But the watch was another win for Hamilton, new tech conquerors. First and best.

Six thousand miles away, another group who were used to being first had been keeping a close eye on Hamilton’s seemingly inexorable march towards digital domination. While the Americans might have won the LED race, Japan’s Seiko corporations had also created a recent tide shift in the world of watches. In 1969, it presented the Quartz Astron, the world’s first quartz watch and the harbinger of doom for the mechanical industry. Seeing first Hamilton with the Pulsar and then RCA (another American firm) create the world’s first LCD clock prototype, Seiko wanted a piece of the action. (LED lights up when current passes through it, while LCD works with a mixture of liquid and crystals embedded between a polarised display screen of plastic or glass, before being backlit to show images.)

“These developments caught our developers’ attention,” a spokesperson from Seiko’s Tokyo HQ remembers. “We immediately purchased liquid-crystal materials to begin working on these technologies.”

“The development of quartz wristwatches was our company’s focus at the time,” says Seiko. “With its [Astron] birth, we created and mass-produced tuning fork-shaped quartz oscillators and a low-power CMOS-IC [a type of small computer circuit]. By utilising these technologies, we thought it possible to deliver accurate time to consumers with a digital display system, and this drove our pursuit of digital watchmaking.”

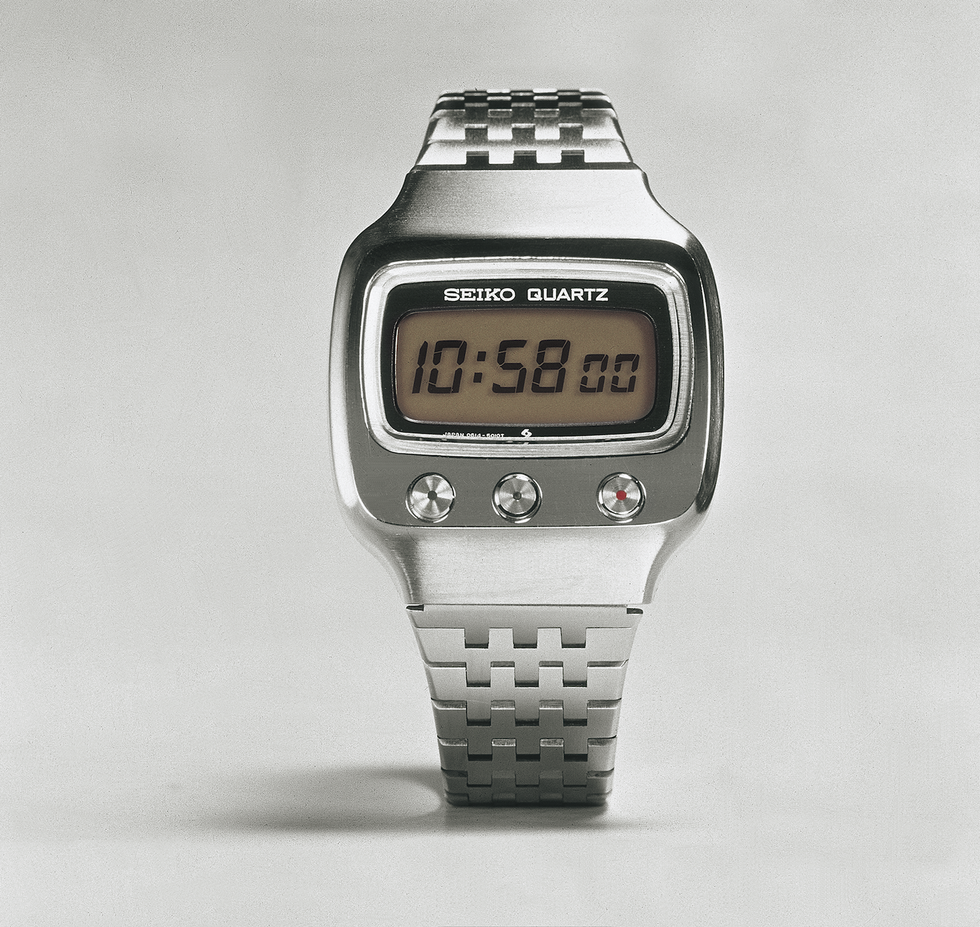

While LED paved the way for digital, it was LCD that would prove to be the key to Seiko’s future digital success. After five years of research and development, in October 1973, in partnership with Epson, Seiko released the Quartz LC VFA 06LC, a watch that made up for its mouthful of a name by being the first six-digit LCD watch on the market. Its hours, minutes and seconds display was both very popular and very reliable. Not one was returned for a faulty screen.

“There was a mix of motivation and curiosity in the challenge of creating something new,” Seiko’s spokesperson says. “As research and development of new technologies progressed, we gained a lot of momentum towards commercialisation of watches that utilised the new technologies, and this energy drove our pursuit to create the digital-display watch.”

In 1980, Seiko even released a TV watch, another first and a nod to the smart watches of the future. “It was company policy to create a watch that not only told the time, but something that was totally new and original. Management would tell us not to imitate or use, even if partially, a competitor’s idea or product, and that the creation must be absolutely unique. TV shows that were futuristic and science-fiction-based were popular at the time, and communication tools which utilised a monitor screen on the wrist were featured in the programmes. Taking inspiration, we as watchmakers thought to create a TV wristwatch.

“We had a group of young employees who knew nothing about TV technology or the difficulties of working with them,” says the spokesperson, ‘‘but this allowed us to take on this challenge with a very free, just-go-for-it spirit, and we were able to go about R&D without boundaries.”

All great empires eventually crumble. While the Pulsar brand was still hugely profitable, by the mid-1970s other cheaper LED watches were being developed and brought to market. Elsewhere, digital clock displays were becoming commonplace, seen on the sides of buildings, on trains and buses, in offices and stock exchanges. What was once the height of human engineering, the epitome of the future and space-age design had become increasingly ubiquitous. American firms had rushed to emulate Hamilton’s success, with more than 70 now producing digital watches, including companies like Hewlett Packard which had zero watchmaking experience.

Yet it was one name, now best known for calculators, which signalled the beginning of the end of the gold rush. In 1976, Texas Instruments announced a $19.95 LED watch, dropping the price to an industry-quaking $9.95 the following year. The digital watch had gone from the wrist of presidents and royalty to the supermarket checkout aisle. In 1977, there were 42m digital watches sold worldwide and yet only 10,000 of those were Pulsars.

Two years earlier, in November 1975, the carefully spoken John M Bergey had appeared on ABC Evening News and made a couple of predictions.

“I would see, that by 1980, perhaps around 22 to 24 per cent of all watches sold — and there will be about 300m of them sold that year — will be solid-state,” he said. “I believe in the early 1980s, perhaps ’81 or ’82, that at least half the unit volume and well over half the dollar volume will be from this little seed that we planted back in 1972.”

Over the following decade the digital watch did indeed become ubiquitous, as identifiably Eighties as Duran Duran or the Rubik’s Cube. Casio, another Japanese giant who produced its first digital watch in 1974, consolidated a hold on the industry with the iconic F-91W in black resin or, if you were fancy, gold-coloured stainless steel. In 1983, it launched the first G-Shock, the DW-5000C, a style that is still a classic today. It proved that digital watches could be both reliable and tough. Then there was the CA-53W, a calculator watch that was seen in Back to the Future and on the wrist of children and teenagers worldwide.

By 1974, Hamilton was under the ownership of SSIH in Switzerland (subsequently the Swatch Group) and, in 1978, it sold the Pulsar brand name to Seiko. The American digital watch industry had been gutted. LCD displays like those championed by Seiko years earlier soon took over — and not even Texas Instruments could keep up. In 1981, it closed its watch division, laying off 2,800 members of staff.

In June 2020, after a stint as head of sales, Vivian Stauffer was promoted to CEO of Hamilton, just in time to oversee the launch of a 50th anniversary edition of the Pulsar (named PSR, Seiko still owns the original patent). It is based on the P2 and is, upon inspection, a dead ringer for the original, although the LED screen that gave engineers so many headaches has been replaced by an LCD-OLED hybrid. The price is also slightly more palatable: £675 for a stainless-steel version and £900 for a limited-edition gold-effect steel PSR. No 18k calculator editions are planned… for now.

“We thought, it was going to be the 50th anniversary of the Pulsar so we have to do something,” says Stauffer over the phone from Switzerland, his voice a calm Alpine lilt, “but it’s not the same team and it’s not the same world anymore. We are not in the US, we are in Switzerland. We thought, ‘Let’s do it but it has to look like the one in the past’. First of all, we had to choose between the P1 and the P2. We went with the P2 because from our point of view it was a bit more edgy and more of a talking point in terms of design. The P1 was a little bit flatter and — with no offence — a Casio lookalike style.

“We could have done a lookalike with a big sapphire crystal digital display,” Stauffer adds, “but we really wanted to give the impression that you have arrived from the 1970s. It was, of course, a big challenge to have a watch with a battery life of a couple of weeks which is water-resistant and meets the standards of today. Also, it’s not something we had in our lab. We had to start from scratch with everything.”

It took Hamilton 18 months of research and development before they were happy with its final product and, in a twist that could be attributed to fate or a global pandemic delaying supply chains, the watch was, like the 1970 original, delayed. A May release pushed back slightly to June. There’s now a five-month backlog of orders for the watch, proving that there’s still a taste for the future, or at least a vision of the future from the past.

“People are looking more and more back to the old days,” says Stauffer. “To objects we had in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. I was with my children at home and they found my old Sony Walkman. And they said, ‘Wow, this is so cool!’ At the time the Pulsar launched, it was the coolest watch you could find. We don’t know why that shouldn’t be the case today and, so far, we’ve been proven right.”

While the original Pulsar couldn’t quite consolidate its stranglehold on the industry, Thiess and Bergey’s work paved the way for a future digital and smart watch industry that is now worth billions. It’s reported that last year, 30m Apple Watches were sold worldwide, a total higher than the entire Swiss watch industry’s combined sales. This is a product that was derided when it launched, pegged as a future white whale. Venerable Swiss watch brands like Tag Heuer and Montblanc now include “connected” digital watches in their line-up. It’s proof that, despite the pocket computers we keep with us through every waking hour, digital on the wrist still sells.

“There is a limit to adding functions onto an analogue watch,” says Kikuo Ibe, the creator of the Casio G-Shock. “But I think digital watches are special because you can attach additional functions freely to make the watch more and more attractive. I am also fascinated by the fun of expressing anything with numbers.”

I ask Mr Ibe about the future of digital watches and the ground-breaking tech that companies are working towards, just as Bergey and Thiess did 50 years ago. “Super heat-resistant technology and super cold-resistant technology is key,” he says. “In the near future, there will be an age when anyone can freely go to space. Outer space is a severe environment, with extremely high temperatures and extremely low temperatures that are not found here on Earth. I have a waking dream that I and my alien friend ‘Taro’ both wear G-Shock together in outer space.

“Working on the development of watch functions that are genuinely designed to improve people’s lives is a challenging and quite difficult part,” says Ibe.

In 2011, Thiess, who after Electric/Data went on to found an electric car company and published more than 25 papers on engineering and filed multiple patents, donated the prototype for the first Pulsar to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History. “I was hesitant to give it up at first,” the then 81-year-old said. “But I realised that it’s a part of history, and people should see it.”

John M Bergey remained in Lancaster, Pennsylvania after his retirement from Hamilton. He owned an enviable collection of Pulsar watches, but according to legend, sometimes around town he would wear another company’s digital watch. When asked why and what happened to Pulsar, he would point to his wrist and say, “‘This is what happened!’ I paid $3.79 for it and it works great.’”

This story is taken from The Big Watch Book 2020, available here

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts