On 26 March 2022, the watch industry changed forever. Around the world, 110 Swatch stores had taken delivery of a radical new collaboration: the MoonSwatch, a crossover design that fused the stylings of Omega’s classic Speedmaster Moonwatch mechanical chronograph with 11 colourful, chunky, quartz-powered bioceramic designs produced by sister brand Swatch. Queues had been forming outside boutiques for two days and, as the security guards unlocked the doors on that Saturday morning, all hell broke loose.

Swatch stores in New York and London lasted just hours before they were forced to close, as police restored order to the crowds outside. Some of those lucky enough to have secured a watch promptly sold them at a profit to those further down the line; others found their patient queueing disrupted by “scalpers” whose only goal was to flip the watches at once. It took almost no time at all for the first MoonSwatches to hit eBay and start trading for multiples of their original price.

Amid the frenzy, Swatch’s official response urged patience and restraint — the MoonSwatch, it had been very clear, was not a limited edition, and everyone would be able to get one in due course. As an appeal to reason, it had all the strength of a parent urging a party of five-year-olds to wait their turn for chocolate cake. Anticipation had been stoked, the launch timed perfectly to take place in the week before the watch industry assembled in Geneva for the Watches and Wonders trade fair. It was clear this was something special, desirable and — in terms of the Insta-bragging rights that ownership would confer — far more valuable than its £207 sticker price.

The launch of the MoonSwatch wasn’t ground zero, but it might come to be seen as the tipping point that marks a generational shift in how watches are marketed and sold. It was the most intense, arresting and visible display of the phenomenon that has been building for the past few years: that of the hype watch.

Before the pandemic, the watch business revolved around annual trade fairs where new watches — normally, a brand’s entire annual offering — would be shown to press and retailers and then, three to nine months later, would appear in stores. This status quo was already splintering, thanks to breakaway brands such as Breitling, Audemars Piguet and Richard Mille, but Covid dealt the hammer blow.

Now, the latest must-have watch might be unveiled on social media or land in our inboxes at any time — encouraging watch fans to stay glued to every possible channel for announcements. Julien Tornare, CEO of Zenith, says, “We used to have one main watch salon, sometimes two. In between, nothing happened. During Covid, we realised we had to drop something new every month, and it’s really paying off.”

The pandemic accelerated another change, too: the rise of e-commerce. With city centres abandoned, online retailers had a boom year, boosted even more by the fact that wealthy customers weren’t holidaying and couldn’t buy cars or drive them anywhere, so instead sat at home “revenge spending”. Newly minted crypto millionaires stayed up late becoming watch nerds, schooling themselves in Audemars Piguet and F.P. Journe. Watch brands — like every other industry — experienced supply-chain disruption, which unbalanced supply and demand even further, but even without that, the stage was set. In isolation, each of these contributing factors would have brought gradual change, but together, catalysed by the conditions of the past two and a half years, they have resulted in a superheated market.

“At Hublot, we have seen record demand,” says CEO Ricardo Guadalupe. “We have been growing every year for the past 15 years, but I have never seen demand like this — especially at the high end — in my whole career.”

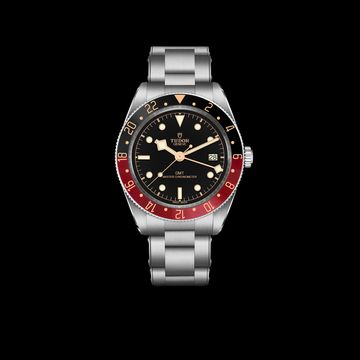

The watch market as a whole might be growing, but that doesn’t mean every model has acquired “hype watch” status. There are a few different categories: first, you have certain models from blue-chip brands. The Patek Philippe Nautilus and Audemars Piguet Royal Oak sit at the very top, together with every stainless steel Rolex in current production, more or less. Individual references such as the Tiffany-dialled 5711 Nautilus, or the 50th-anniversary “Jumbo” Royal Oak, have been the epicentre of hype. Demand for top-tier hype watches is so high — watch forums talk of 20-year waiting lists for the Rolex GMT-Master II — that there has been a trickle-down effect, making sell-out successes of models like the Girard-Perregaux Laureato and Zenith Chronomaster Sport.

Second, there are the limited-edition collaborations. Not a new concept, but where once watch brands worked with car-makers or air-display teams, recent collabs have paired watchmaking with the interests of millennial millionaires: streetwear, crypto, gaming and contemporary art. Tag Heuer and Nintendo. Audemars Piguet and Marvel. H. Moser unveiled a collab with streetwear label Undefeated; Jacob & Co slapped Supreme’s logo on a five time-zone, 47mm monster. Hublot — perhaps the arch-collaborator par excellence — has released limited editions with artist Takashi Murakami and designer Samuel Ross.

“If we do what is traditional, we are dead,” says Guadalupe. “We see other brands following what we’re doing, meaning we’ve possibly got the right strategy.” He’s eager to stress that the hype around limited editions can’t sustain a business in itself, but is fundamental to marketing “core” products. “The limited editions, they’re the watches we talk about. But they make up 15 per cent of our business. That’s why we go from one thing to the next, one artist to another, or a chef, or whoever. Take the Murakami watches. We have done two lots of 100 pieces, which is in a way nothing, but it’s a lot from the communication point of view. It’s rare, it’s being sold at three or four times over retail [price]. That’s what builds the brand.”

Our third flavour of hype watch is a little different — described by some as “hype out of the box”. This typically comes from small, young brands whose business model is built around a cycle of drops. They’re teased on social media and sold primarily or exclusively direct to consumers online. Despite relatively affordable prices — £500 to £5,000, or so — their appeal is primarily to seasoned watch collectors and, as a result, new pieces tend to sell out almost immediately.

Think of them as the rare Japanese denim, or low-volume British-made sneaker, that unless you’re on the right mailing lists, awake at the right time or aware of which unmarked backstreet door to knock on, you don’t have a chance of buying. Their names would mean nothing to anyone perusing the window display of their nearest Goldsmiths — Furlan Marri, Kurono Tokyo, Massena Lab — but, in the right circles, will get you more attention than yet another Rolex.

Straddling these last two groups is Bamford Watch Department. For the most part, it’s known for its multi-collaborative limited editions — such as the quad-X TAG Heuer Carrera produced with Porsche custom shop RUF and hype bible Highsnobiety, which landed this August — although, increasingly, BWD is building a core collection that’s always available. Despite years of working on hyped-up drops, founder George Bamford was taken aback this year when the in-store launch of a collaboration with G-Shock went sour.

“People were pushing and shoving those at the front of the queue out of the way. Carnaby Street security tried to stop it, and it got out of hand. I had my kids in store and they had to be escorted out by security, and then the police came and closed it down. It became a bit nuts.”

An in-store drop has a lot going for it. You get to build a bit of a buzz, indulge your inner showman, stage a physical demonstration of your popularity; but the real business gets done online. Bamford Watch Department sold out its entire stock of the G-Shock collab — more than a thousand orders — in a minute and a half. Such avalanches aren’t entirely new — Omega took deposits online for 2,012 “Speedy Tuesday” Speedmasters in under four hours, and that was in 2017; TAG Heuer’s special editions for Hodinkee performed similarly, and set the bar for hype drops ever since. However, “the time frame has got shorter and shorter,” says Bamford. “For us to sell out in 90 seconds online, that’s unreal.” The rush, in every sense, is incredible. To see the orders fly out, and the money fly in, that quickly; to see such intense, instant validation of your creation. But, like all highs, it doesn’t last — and has a few problematic side-effects.

“People see it as the new normal,” says William Massena, founder of Massena Lab. “Then you release a watch and it doesn’t sell out in 24 hours, they’re asking, ‘What’s wrong?’ New collectors in particular think success is measured in the speed of the sell-out of the watch, and that’s very dangerous for the industry.”

“There is a duality to it — my ego loves selling out quickly,” says Bamford. “But we have a plan in place, for three weeks of activity for each watch. When it sells out in a day, we panic and scrabble around, catching our tails. I like an initial ‘boom’ but you want people who, maybe, were on holiday, to still be able to get one. I thought it would be one of the most positive feelings, going on holiday after the G-Shock launch, but I was down, I was depressed. People were messaging me saying ‘I’m going to come after you’; really offensive messages. It left a sour taste in my mouth.”

The shift to e-commerce has been hailed as a sign that the watch industry is moving with the times, but it poses a constant challenge both in terms of offering a smooth, fair process and managing customers’ expectations. Collectors will tolerate the mad competition to score the latest watch, as long as they think they’ve got a fair shot.

“When we were packaging up the watches, about 50 orders were to the same address,” recalls Bamford. “We had said one per person, but there were a bunch of fake names, made by a bot. So we voided 50 orders and put them back online. I made a video for Instagram saying we had a few watches coming back online, and before I posted the video, so within about 15 seconds, they had sold out again! There are ‘sniffer’ bots that are ready and poised to buy the minute something comes online.”

Founded in 2014, Ming produces low-volume, contemporary takes on traditional watchmaking. Based in Malaysia, working with Swiss manufacturing and assembly partners, in many ways it embodies a certain vision of a 21st-century, digitally native watch brand.

“Where we are today is not a deliberate consequence of saying we’re going to be a 100 per cent online brand, doing drops and all that. It’s a result of how the market reacted,” explains founder Ming Thien. “It’s not that we wanted to make limited runs and use the hype train — we have a lot of ideas. To stand out, we had to be doing something interesting, so we’d do one thing and move on to the next.”

Whether by design or not, Ming has found itself facing the same challenges as BWD. “When we were on Shopify and PayPal, everything sold out too quickly and people got pissed off. Selling out is great but selling out too quickly is not, so we slowed the process down. We built a custom e-commerce system from scratch, with a lot of anti-bot countermeasures, because what we needed didn’t exist. With every launch, we take on some feedback from the last ones — staggering launches for different time zones, for example. Existing customers know what it used to be like, and know that it’s better now, but new customers come to us with expectations of e-commerce on a level that Amazon or Apple does it, and we don’t have that kind of budget.”

An intrinsic part of the conversation around hype, which cannot be ignored, is what’s known as the secondary market: the watches being sold on eBay, StockX, Chrono24 and elsewhere. As the hype has taken hold, these platforms have taken on a slightly homespun stock-market feel, and you’ll find the same caffeine-infused attention to the “market price” across Instagram and YouTube as a result.

Historically, major brands turned a blind eye to resale platforms — largely seen as facilitating a grey market of “as-new”, unsealed watches — but in the world of hype they are the new frontlines. Watch collectors may disdain the “flippers” who sell MoonSwatches, Rolexes or Royal Oaks for a big profit — but it’s the inevitable result of the industry they love enjoying such success. Everyone wants their favourite musician to do well; no one wants them to do so well that they’re on Radio 2 and headlining Wilderness Festival.

Mainstream brands are still diplomatic in their public statements: “We are lucky at TAG Heuer that both our vintage and contemporary watches show a stable appreciation,” commented CEO Frédéric Arnault. “We are also very protective of the value of our best-selling pieces, such as the TAG Heuer Monaco, for which there are waiting lists. We only produce a set number. We could sell a lot more, but we want to ensure the quality and desirability of this iconic timepiece remains at its highest.”

Others are more open in their recognition that flipping helps create demand in the first place, for better or worse. “You want a bit of flipping,” says George Bamford. “I hate the idea of it but you want some… although, the amount of trouble I get because of flippers — with my top clients saying I don’t care about them. In some ways, the flipper being there, validates to you, as a buyer, that it may go up.”

“I think it is kind of dangerous,” says Thien, “because your demand isn’t driven by your product. It’s driven by external factors that have nothing to do with the integrity of your product. It’s good to have some secondary demand, because we reinforce value for the primary customers. But I don’t feel comfortable with people having to pay four or five times the price. Say we design a watch to cost CHF3,000 at retail: we want to manage the secondary market so that someone picking one up, which may be their first experience with us, isn’t paying CHF10,000 for it, and having expectations at that price point rather than a 3k price point. It’s not in our interest for them to pay more and then feel disappointed.”

As founder and CEO of specialist dealer A Collected Man, Silas Walton deals in the most desirable vintage and contemporary independent watches. “We have stayed largely away from the hype end — the margin has been less interesting, historically, at the more commodified end of things. Today, the secondary market is significantly in excess of the retail price; as long as that remains, it keeps our primary market looking like good value — the privilege of being allocated a watch will be too good to turn down. The flipping side of things is unhealthy, but there are current ‘hype’ brands that are a bit holier than thou — they’re selling for multiples of their value today but you couldn’t sell them three or four years ago without 30 to 40 per cent off. Some big, family-owned Swiss brands used to come down hard if you sold one of their watches but now, from what I understand, as long as it’s not within a year, they’re more tolerant. Because you have to be. You’ve created the monster, and speculation, like it or not, is part of the market now.”

There are two obvious ripostes to out-of-control flipping and impossible-to-find references: increase the retail price and increase supply. Brands are reluctant to weather the PR storm of the former, and the latter is harder than it sounds. Controversy rages over whether Rolex could, or should, increase supply of its steel watches. With annual production in the region of a million watches, the popular perception is that all scarcity is artificially engineered. But talk to any other brand, no matter their size, and you’ll hear the same story: we literally can’t make them fast enough. “We cannot double production overnight,” says Hublot’s Guadalupe. “To increase by 10 per cent in a year is already a big challenge.”

A. Lange & Sohne’s Wilhelm Schmid agrees. “Waiting lists put us in the unpleasant situation of having to ask for apologies. But the production for certain models involves a very high level of craftsmanship and is therefore time-consuming. I’m pleased that most of our customers know us well enough to understand this.” The problems are exacerbated at smaller brands, whose supply chains can be disrupted when bigger players snaffle up manufacturing capacity. For Ming Thein, estimating demand “is the hardest conversation we have. People seem to think we only place production orders once we’ve got orders from the market. That’s not true. The reality is lead times in the market are 18-24 months; with delivery times of six to nine months for our watches, there’s no way that works. We are working to bring delivery times down but, with the state of the industry at the moment, every time we close the gap, it gets longer again. When the big brands saw revenge spending and the boom of e-commerce, they went in and placed orders for the next five to six years of product. A lot of suppliers, at the start of the pandemic, shrank operations to be conservative, to survive, and then everyone got slammed with demand.”

“Historically the industry has been quite slow, and the speed of the world has accelerated so much that we need to adapt,” says Julien Tornare at Zenith. “Fashion is much faster in its cycles. It will have an impact on production but we want to put the client first, not the company finances. If you make a big noise and they have to wait 6-12 months to get the watch, that’s a thing of the past. The younger generation isn’t going to wait. And if your watches aren’t available at all — if they’re in the window for exhibition only — some clients get very upset and frustrated. It’s not good for the whole industry; we’ve got to treat customers properly and not be too arrogant.”

Hype, then, doesn’t seem such good news for the watch business after all. If one end of the train accelerates — the speed that watches sell out and the increased frequency of drops — but the other end, the business of actually designing and producing them, can’t speed up to match, something has to give. But Walton, for one, doesn’t see “hype” as the culprit — rather, it’s just one symptom of a generational shift. “There’s nothing inherently pejorative about the term ‘hype’. It’s more reflective of a cultural phenomenon that’s part of a younger, more fashion-attentive behavioural pattern that’s almost normal now. There are valid criticisms of the way things are being done, but I think more than anything it’s about a divergence in the balance of power, which is frustrating for collectors who liked having time to consider a purchase, even having to be courted and entertained — and receive appreciation from the seller when you decide to buy. When you drop a watch, you’re shifting the power from the buyer to the seller.”

It’s no coincidence that the onset of the hype economy has manifested itself via social media, e-commerce and online peer-to-peer marketplaces. This is the watch world’s digital revolution, and the real challenge is to see how this traditional, relatively slow-moving business can adapt.

This article first appeared in the 2022 edition of Esquire's Big Watch Book