One reason I have a soft spot for sports car racing — as opposed to Formula 1 — is the enduring existence of the “gentleman racer”. The idea that a talented amateur can still take his or her place on the grid today, albeit not at the very highest levels, adds to the romance of it all, even if in 2019 the typical “amateur” driver is likely to be a competent businessman who contributes more to the team’s balance sheet than the results sheet. Things were a little different 40 years ago, however.

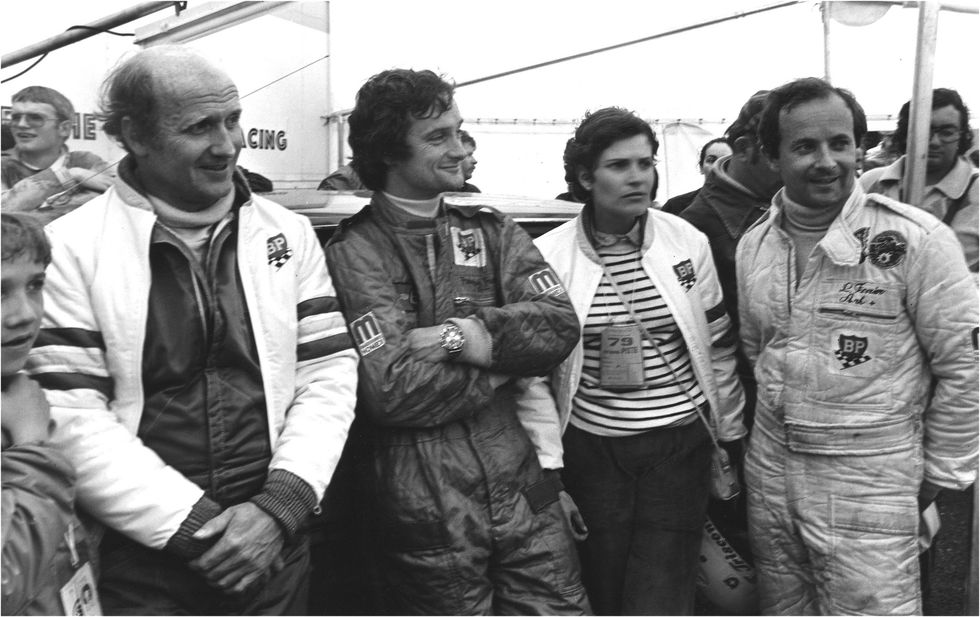

It wasn’t necessarily better — this was an era where death could lie literally around the next corner, after all — but it’s hard to deny the allure of ordinary men with the right blend of talent, pluck and, well, drive being able to come wheel-to-wheel with legends of the sport. Alongside the professionals lining up on the grid on 9 June 1979 at the Circuit de la Sarthes (among them Jacky Ickx, chasing his fifth Le Mans win) were entrepreneurs, a film producer, an alpine skier, at least one TV presenter, Pink Floyd’s drummer Nick Mason and the band’s manager Steve O’Rourke, and Hollywood hero Paul Newman.

It’s not known for definite whether Newman wore his now-famous Rolex Daytona chronograph during this particular race, but he must have driven carefully regardless, as he and his teammates placed second overall.

Standing on the other side of the podium was perhaps the unlikeliest trio of all. Racing under the auspices of the Kremer race team (whose other car had claimed first place), Laurent Ferrier, Francois Sérvanin and Francois Trisconi were no strangers to Le Mans, but all three were amateurs, able to take part in only a handful of races each year. In five previous attempts, Ferrier had only finished the race once, coming 11th (albeit first in his class) in 1978. After the race, he would fly back to Geneva and report for work as usual at Patek Philippe, where he was making a name for himself in a world far removed from knife-edge racing, fatal crashes and screaming fans.

Young men growing up in the Jura mountains in the Fifties and Sixties tended not to become racing drivers. They were the sons, grandsons and great-grandsons of watchmakers and Ferrier was no different. His father ran a restoration workshop opposite Vacheron Constantin and it was assumed he would follow in the family trade.

As a boy, he was fascinated by motorsport. “I loved motor racing magazines,” he recalls, “although we only had one, the equivalent of the English Motor Sport magazine. My favourite drivers were Jim Clark and Jo Siffert, and I had dreams of being a driver in Formula One or the 24 Hours of Le Mans.” These days, if those dreams are to become reality, young drivers’ talents are recognised at an early age.

For Ferrier, however, the first indication he might have a natural aptitude behind the wheel came as he neared adulthood: “In Switzerland, we had no racetracks to speak of, and we couldn’t do karting either, but when I was 18 I had a Fiat 500, and on the snow I handled it pretty well. That was where I first found the real pleasure of driving.”

By his early twenties, Ferrier had fallen in with a similarly obsessed group of petrolhead friends and had upgraded from his Fiat to a rally-prepped Hillman Imp Sport one-litre that had been entered in the Monte Carlo Rally by Swiss driver Patrick Lier. Ferrier later served as Lier’s co-pilot in the Junior Monte Carlo Rally, but this wasn’t the auspicious start in motor racing he might have hoped for. “I was sick for the entire race!” he laughs.

The Imp was good enough to see Ferrier taking part in local rallies, but with a youthful hunger for progress he was soon onto his next set of wheels — a Lotus 18 purchased together with friends. “We used to race together on a small circuit 10km from Geneva called Monthoux. It was very small, and this was just for the pleasure of racing on Saturday mornings.” This humble proving ground — circuit is almost too grand a word — has since been absorbed into the suburbs of Geneva, but if you look on Google Maps (search for “L’Impasse de la Râpe”) you will see the clear outline of a rudimentary racetrack, barely a kilometre long.

A visit to a driving school in Belgium followed, where he was selected for the final group from a pool of more than 300, but disqualified for spinning out. It had given him the know-how needed for the next step, however, and soon the Lotus was being sold to make room for a purple Formula Ford. “That was when I really started racing in international races,” he says. “I won my second Formula Ford race at Hockenheim in 1974, but I never completed a full season. After that I was able to enter the world endurance championships, racing at Monza, Spa, all the great courses. I drove a Chevron Sport B21 two-litre, a Lola T294 and a Porsche 908. But I couldn’t do all the races, I could still only do four or five in the season.”

By now 28 years old, Ferrier was lining up alongside Jochen Mass, Loris Kessel, Henri Pescarolo and Arturo Merzario — top-level racers with F1 seats and motor sport in their veins (later, in the Eighties, he would also face off against Eddie Jordan, Walter Röhrl and Tiff Needell). One wonders how it was received back in the Vallée de Joux; did it feel like some kind of double life, as he juggled with his duties at Patek Philippe? And what did his parents think?

“My father was a watchmaker and he didn’t expect it, but he always supported me morally. It was more dangerous than it is now, so certainly they worried, but they saw that it was my passion and they accepted it. They were good parents!”

As for his colleagues, it seems the part-time passion of an up-and-coming watchmaker (he would eventually be made technical and product director for Patek Philippe) was greeted with polite acknowledgement rather than effusive praise. When he returned from his life’s greatest racing result, “people said, ‘Well done’, of course.”

Throughout our conversation Ferrier, 72, is extremely modest about his achievements. And the truth is that to meet him today, you would not immediately credit him with the steely nerve of a natural-born racing driver. Silver-haired and quietly spoken with an avuncular smile, he’s more Father Christmas than Fast and Furious, but like the watches bearing his name, he is possessed of hidden depths.

Certainly he had what it took to make a go of racing full-time; a trawl through race records shows a number of top 10 placings in races that are no Sunday jaunt: 1,000km events at Monza, 500km at Imola, and six hours at Mugello and Silverstone. The problem was money; racing was too expensive to ever become more than a part-time passion. At the early Formula Ford races, Ferrier was racing for a fellow Swiss, team owner Michel Dupont, who rented two cars for CHF10,000 apiece per race. Added to that were fees of around CHF3,000 per driver, and considerable running costs on top.

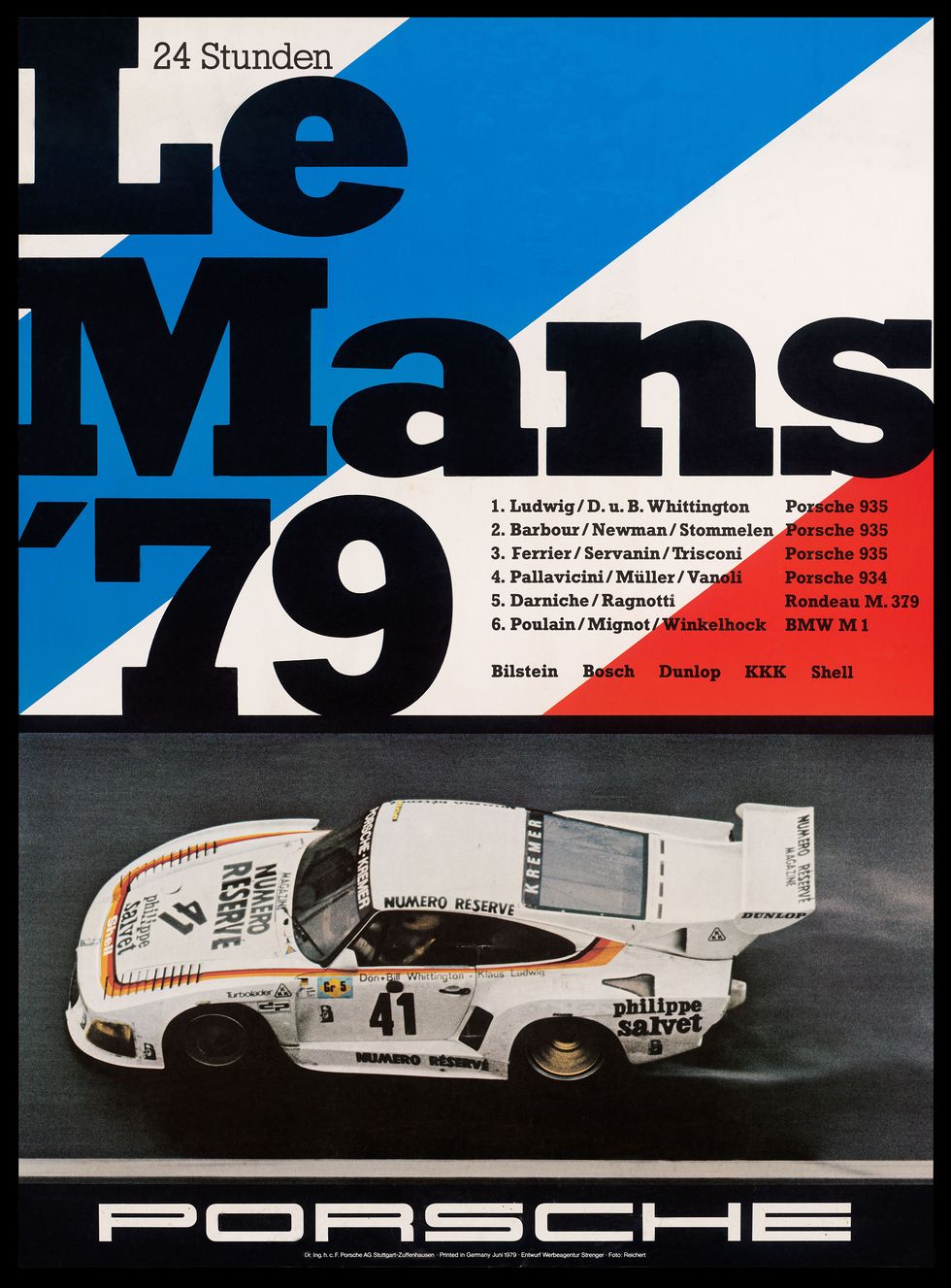

As the Seventies drew to a close, racing at Le Mans was dominated by homologated versions of road cars — and by Porsche’s 935 and 936 in particular — which could reach speeds of 220mph on the Mulsanne Straight and run more reliably than their privateer competitors.

Laurent Ferrier could vouch for this first-hand: his first four attempts at Le Mans in a Lola and Chevron were all curtailed by mechanical failure. For 1979 he had secured a drive for Kremer Racing which brought him into the 911-based Porsche 935 for the first time. “I had never driven it before Le Mans! It was very impressive. We were confident, but as always with the 24 Hours of Le Mans, as in the years before, in ’76, ’77 and ’78, you could be at the head of your category and suddenly break down, because at that time the cars were always breaking down. But this year, with a car that was a lot more reliable than the two-litre prototypes we never had any sign of a problem.”

Despite being fresh into this particular machine, Ferrier was faster in testing than Formula One driver Jean-Paul Jarier in the same car — an anecdote he delivers with a rare note of unabashed pride; you sense his grandchildren will be hearing this one when the time comes. The race itself turned on the halfway point, when light rain gave way to thunderous downpours. Jacky Ickx, hot favourite in a works team Porsche 936, was forced to retire (and subsequently disqualified).

Ferrier won’t be drawn on the finer details of the race — guaranteed to have been a firm test of both man and machine — instead preferring to remember Le Mans at its most euphoric, his voice intensifying as he reminisces: “I always found it a magnificent course. My strongest impression of it will always be the first time I drove the track and passed under the Dunlop Bridge. That was always a great feeling. And, of course, it was very different to all the Formula Ford races. There, there was no TV, no people, only the drivers and the cars. At Le Mans, I remember the young women screaming and cheering passionately!”

Shortly after the race, the first seeds were planted for Laurent Ferrier’s eponymous watch brand. As a celebratory gift, Ferrier gave his friend and regular team-mate Francois Sérvanin a Nautilus (provided to him by none other than Patek Philippe CEO Philippe Stern). The two had talked before about founding their own brand and Sérvanin pledged that one day they would do it. It would in fact be 30 years before he would return to his old friend with a now-or-never opportunity; in 2008, Laurent Ferrier was founded with Sérvanin’s financial backing.

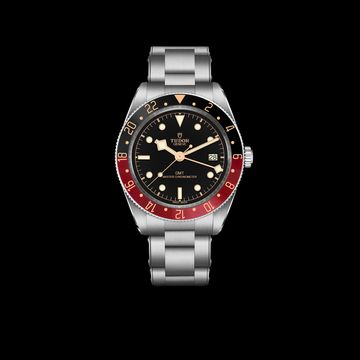

Despite its genesis, there was never any intention of forming a “motoring-themed” brand; Ferrier was too well steeped in haute horlogerie by that point. Indeed, although the bare facts of the Le Mans story have formed a part of the brand’s narrative, it was a complete surprise to hear Ferrier intended to commemorate it with a watch.

But then, the Grand Sport Tourbillon is hardly your typical motoring timepiece. “As you can see,” says Ferrier, “it isn’t a monopusher chronograph!”

Despite speaking previously of his desire to one day bring out a chronograph movement, the challenge of producing one to his standards is immense, and apparently no steps have been taken in that direction so far. The decision to make this watch was only taken last year, and at 44mm across its the largest piece Ferrier has put his name to (although it doesn’t feel anywhere near as big in the metal).

The hour markers and hands are more extreme evolutions of what has gone before, but fall some way short of being outright sporty by most brands’ standards. The appearance of a rubber strap is in many ways the biggest departure from previous norms, although what will be more likely to capture many watch fans’ imaginations is the possibility that it could well lend itself to an integrated bracelet design — in a year when several others including Urban Jürgensen are doing the same. In that sense, it is very much a watch of the late Seventies — a “form watch”, as Ferrier describes it — and the connection to the Nautilus feels appropriate.

The presence of a tourbillon might also seem odd for a motoring-inspired watch, but reading between the lines we would expect that, beyond the initial limited run of 12 pieces, the watch may reappear with a new movement in the future. This year also marks a decade since Laurent Ferrier’s first tourbillon watch; a little extra milestone Ferrier is keen to observe.

The brand he founded 11 years ago is today going from strength to strength, broadening its aesthetic range not only with the Grand Sport but through the Arpal collaboration with Urwerk and the Bridge One, as well as embracing period styles with the Montre Ecole. Laurent Ferrier last raced in 1985, at the hurricane-lashed Fuji 1,000km. He left Patek Philippe shortly before he was due to retire, and now works alongside his son, who did as young men from the Jura tend to do by following in his father’s footsteps. He drives a Range Rover Evoque “because it’s good in the mountains, especially in bad weather” and he still admires Formula One.

“The races have become so complicated today, but I’m impressed by all the drivers,” he says. “I like Romain Grosjean, because he’s from Geneva, but he has no luck!” Maybe he should have been a watchmaker instead.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox.