Not long ago, Kate English arrived home expecting to find her husband as she’d left him, getting on with the DIY. Instead he was in the kitchen, having a cup of tea with someone she wasn’t expecting. It was Harrison Ford. His helicopter was in the garden.

“My wife was going, ‘Why is he here?’,” recalls Giles English. “It was a little bit random. But he’s a lovely man. All he wants to talk about is planes, watches and cars.”

Ford had landed in the right place. If planes, watches and cars are your thing, then Giles, along with his brother Nick, founders of Bremont Watches, are your guys.

In mid-July, for example, we found Giles at Silverstone, in the garages of Williams Racing, the Formula 1 team that Bremont sponsors. As driver Logan Sargeant’s car was being put together, Bremont’s minimalistic sans-serif logo, underscored with an old-fashioned airplane propeller, was visible on the decklid. (Sargeant, wearing the latest Bremont-Williams co-branded watch, soon appeared in his overalls and gave Giles the big thumbs up. “Best of luck,” Giles said.)

Bremont was founded after Euan English, Nick and Giles’s father, was killed and Nick was badly injured when Euan’s World War II vintage Harvard aircraft crashed taking off from North Weald, an airfield in Epping Forest. Euan was 49, Nick was 24. After a stint in the City, and spurred on by their father’s untimely death, the brothers decided the clock was ticking, and quit finance to follow one of several engineering passions they’d shared with Dad — restoring historic aircraft. In 1997, two years after the crash and much to their mother’s dismay, they were back in the air — only for another mishap to see them make an emergency landing in their German biplane in a field in northern France. The field’s owner, a 78-year-old farmer, took pity on them. His name was Antoine Bremont.

Since founding Bremont in 2002, Nick and Giles have overseen dozens of British aviation and automotive-themed watch releases, including a successful line with Martin-Baker, the Buckinghamshire-based manufactures of ejection seats. With an ear for a good story and an eye for good marketing, the Bremont bothers made their MBI chronometer available solely to pilots who have survived a live ejection in a Martin-Baker (MBII and MBIII lines are available to anyone, irrespective of fighter-jet experience).

This led to a raft of commissions for special-edition watches provided exclusively for a wide variety of military units around the world — generating significant credibility and today providing an estimated 25 per cent of Bremont’s business. Tom Cruise, Tom Hardy and Ewan McGregor became fans. Harrison Ford, too.

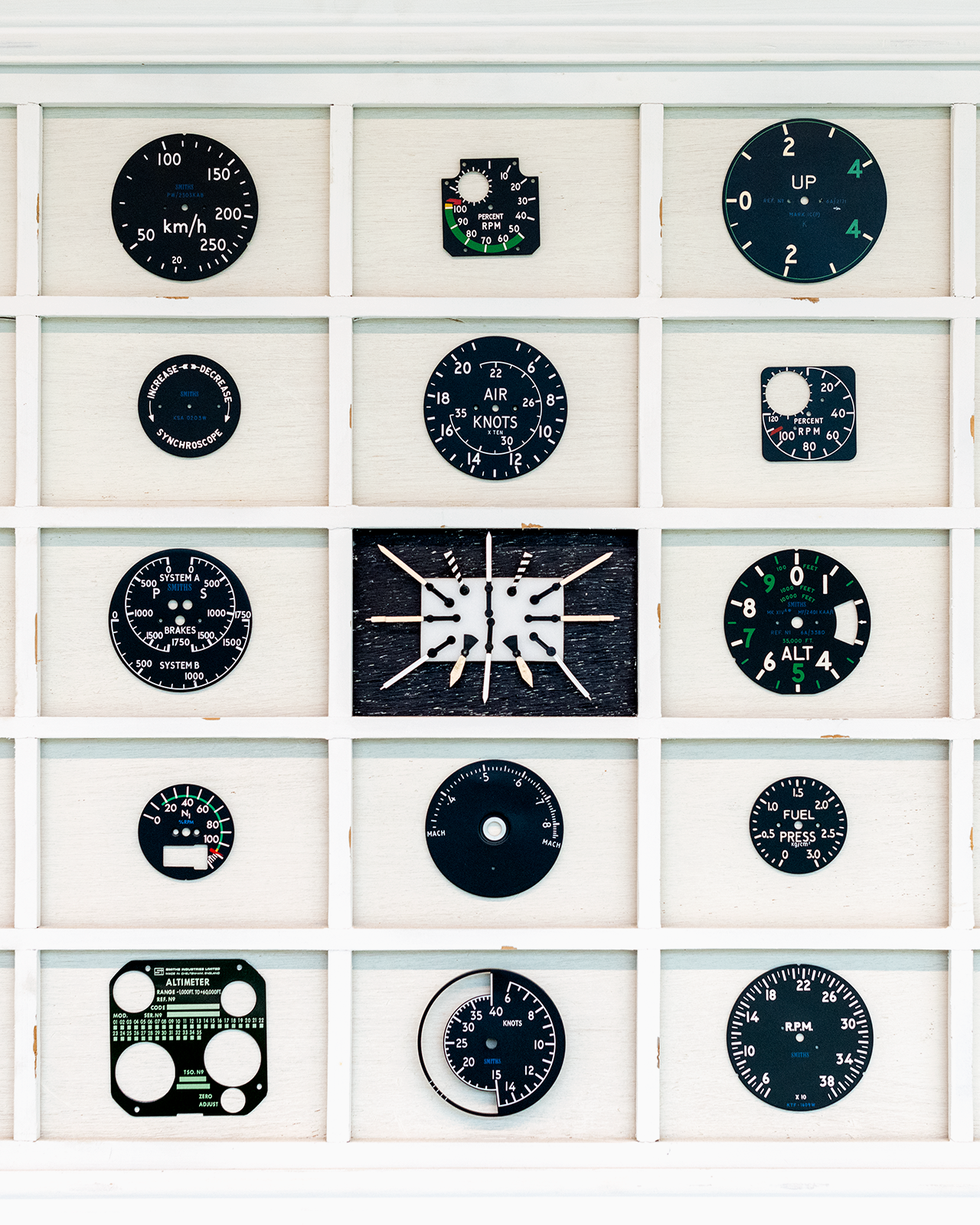

There were other eye-catching models that continued the theme of British derring-do: the Codebreaker, whose dial incorporated wood from the hut in Bletchley Park where Alan Turing helped bring an end to World War II; the Victory, a watch containing oak and copper from Lord Nelson’s battleship; and the Wright Flyer, a watch fitted with a piece of muslin from the wing of the Wright Brothers’ first aeroplane.

These were bold ideas. But Bremont’s ambitions were bolder still.

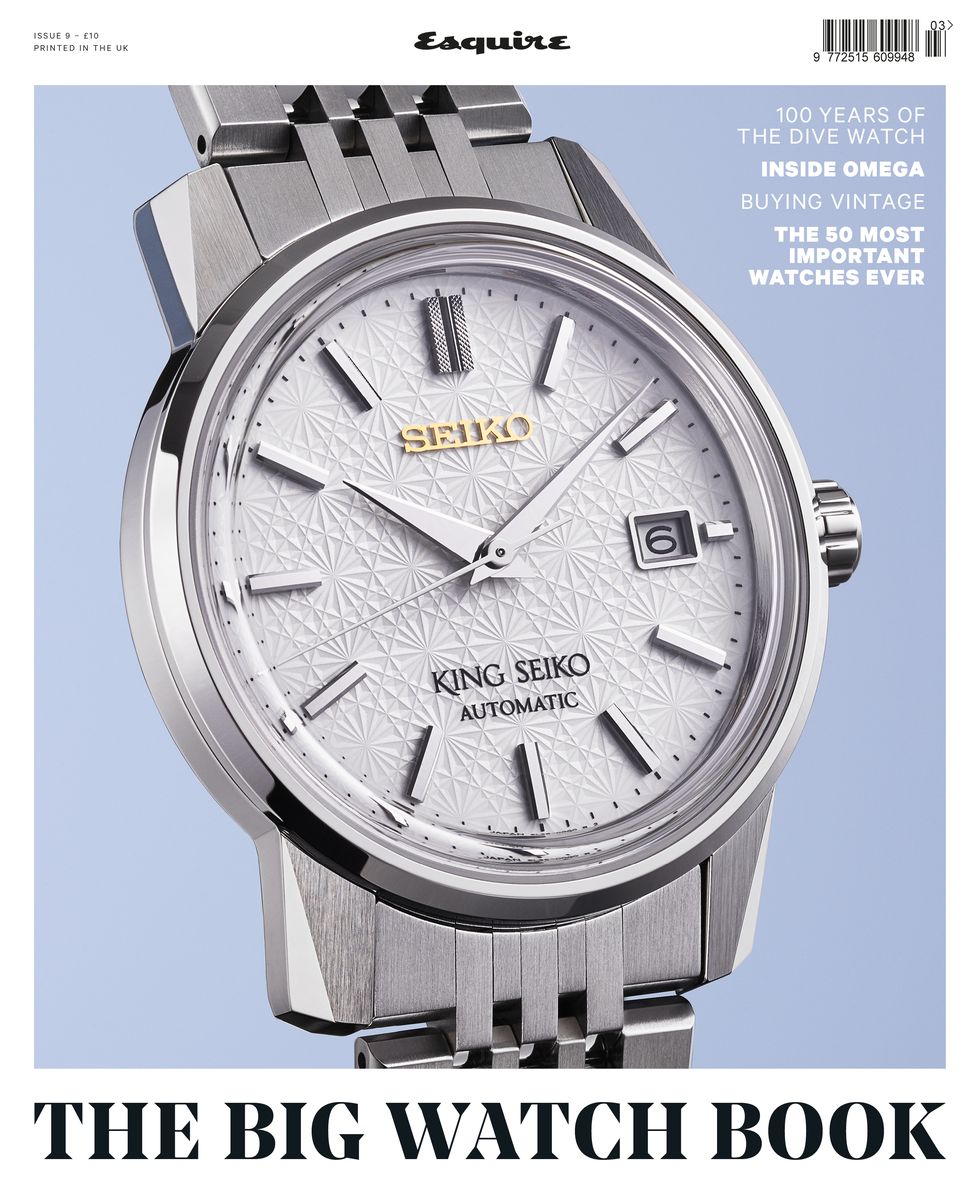

In 1880, half the world’s watches, about 200,000 a year, were made in Britain (most major watchmaking innovations, including the balance spring, the chronograph and automatic winding are also British). In the 21st century that number had dwindled to, effectively, none. Switzerland is king now. British watch brands certainly exist — nice ones: Fears, Marloe, Farer, anOrdain — but they are designed here and made overseas. The UK can also claim two of the greatest watchmakers alive anywhere today: Roger Smith, based on the Isle of Man, and Rebecca Struthers, from Birmingham, who make everything by hand. The former produces 10 watches a year, the latter “two to three”.

Nick and Giles’s ambition was to bring industrial watchmaking back to Britain. In 2021, and backed by investment of more than £20m, they opened Bremont’s Manufacturing & Technology Centre, also known as The Wing, a 35,000 sq ft, architecturally striking state-of-the-art complex, outfitted with the kind of bespoke machinery you expect to see in a Swiss manufacture, except it is in Henley-on-Thames. Bremont now produces about 10,000 watches a year, with capacity, Nick English says, to scale up to 100,000. Also in 2021: The Wing began making its own “Bremont manufactured movement”, the ENG300, a fiendishly difficult and expensive undertaking, and something it had been explicit about wanting to achieve from the get-go. (There were many false starts and wrong turns along the way, and, should you chose to go there, the internet has much to say about how much of the ENG300 can be said to be produced “in house”, and what “in house” really means anyway. Either way, it is an immense achievement.) It is the first industrially produced movement on English soil since Smiths of Cheltenham’s in 1946.

“What Bremont are doing is phenomenal,” says Rebecca Struthers, who is also a historian, and author of Hands of Time: A Watchmaker’s History of Time. “The Wing is absolutely incredible. To see a factory of that size outside Switzerland or Germany and that many people being employed in the UK making watches, is just incredible. It’s what we should have been doing 150 years ago. Had we done, maybe we wouldn’t have lost the industry.”

Nick and Giles got Bremont off the ground with their own money, but took on investment quickly. They priced their watches quite high — necessarily so, Nick says, to reinvest in the company.

John Ayton, co-founder of the jewellery brands Links of London and Annoushka, was a seed investor in 2007 and Bremont’s first chairman.

“Because Links was in the best jewellers in the UK, Nick and Giles came to see me,” Ayton says. “I was very impressed. But it was difficult getting those first few retailers. Taking on the Swiss was all part of the narrative. Being the challenger brand you need something to challenge. And the whole idea was that our mission was to restore the fortunes of the British watchmaking industry, which had been taken away from us unfairly during World War I.”

Things have certainly been going in the right direction ever since, although The Wing is still routinely described as “Bremont’s £20m gamble to revive British watchmaking”.

Then in 2023, two things happened that seemed to shorten the odds.

In January, Bremont announced it had secured a further $59m (£48.4m) from the American billionaire Bill Ackman (apparently after he liked some watches he bought), alongside existing investors, Hellcat Acquisitions. Ackman is the founder and CEO of hedge fund Pershing Square Capital Management, with investments that include Netflix, Domino’s and the Canadian Pacific Railway. Forbes estimates Ackman’s worth at $2.8bn (£2.3bnf). Following the announcement, the Financial Times valued Bremont at more than £100m.

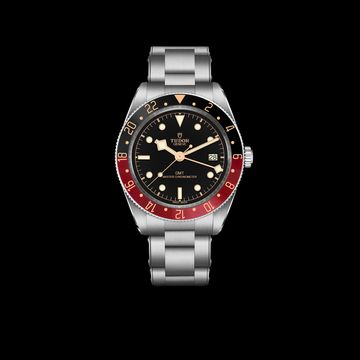

Then in May, Bremont appointed a new CEO, Davide Cerrato. This blindsided the industry for several reasons. Cerrato is as close as the watch world gets to a Marc Newson. With stints at major Swiss brands Panerai, Montblanc and Tudor, as well as the more avant-garde HYT, he has a reputation for digging into the archives, drilling down into a brand’s DNA and creating new-yet-familiar hero products that go on to become highly successful. This happened most effectively at Tudor, which until 2012 was known, if at all, as the underperforming sibling to Rolex, made by the same company and sharing some of its qualities, though not many of its sales — so much so that it had stopped being sold in America, Europe or the UK. As head of marketing, design and product development, Cerrato relaunched the brand with a single model — the Black Bay. A stainless-steel dive watch with a burgundy bezel and a chocolate-coloured dial, it recalled different elements of vintage Rolex and Tudor submariners, without being a reissue of a specific model. As one commentator put it: “Tudor distilled 50 years of submariner history into one cohesive design.” Crucially, it was priced at a relatively cheap £2,600 — so-called “entry-level luxury”.

There have been many, many Black Bays since. “Cerrato’s vision, with both the Black Bay specifically, and a wider project of triangulating the revival around heritage, and taking a very emotive, colour and style-led approach, turned Tudor into a cutting-edge powerhouse,” says one industry expert. “Its influence has transformed the mid-tier market and created an entire genre in vintage-style sports watches.” With sales of around £495m last year, according to Morgan Stanley, Tudor can now claim success.

Lastly, Cerrato is an Italian with an Italian’s sense of style, given to bowties, double-breasted suits and, on occasion, fedoras. Nick and Giles, on the other hand, are more traditionally British jeans-and-jackets kind of guys.

So, it was an unexpected match. What fruits might this Italo-British union bear? With a pile of cash in the bank and a visionary new CEO thumbing the chequebook, where might it go? Could Cerrato deliver another Black Bay? And what did it all mean for Nick and Giles?

Back at Silverstone, Cerrato had arrived and was strolling around the Williams garages, not entirely blending in. He was wearing a tobacco-coloured, double-breasted linen jacket, a knitted cream tie, pleated white trousers and suede tasselled loafers. There was a red flower in his buttonhole, a brown-and-white hanky in his top pocket and doubled-bridged acetate sunglasses on his nose. Bremont’s Longitude steel dress watch was on his wrist.

That evening Williams hosted a dinner in its hospitality suite in the paddock, the menu being provided by Tom Kerridge’s upmarket catering company, Lush. The once-celebrated British Grand Prix team had appointed a new principal ahead of the 2023 Formula 1 season, James Vowles, imported from the more successful and flashier Mercedes. As Cerrato took his seat at one side of the table and Giles at the other, the parallels were hard to ignore.

“There is really a lot to do,” Cerrato said, who was seven weeks into taking on Bremont. “Tweaking and sharpening what was foreseen [ie: the releases already planned] for October, November and December. And then next year for Watches & Wonders [the annual industry trade show held in Geneva in April] we will be able to come with something new. And that will be the big relaunch of the brand.”

Cerrato had relocated to London from Geneva, where he had lived for the last 15 years, bringing with him his wife and their cat Chanel. He took the third apartment the relocation company showed him — in Kensington, not far from the Science Museum. Walks in Hyde Park were a definite plus, though he was still adjusting to the British diet.

“I struggle a bit because we like cooking,” he said. “And in Geneva we have very nice food-shopping places.”

Sitting within the grounds of a private estate and facing the fields of the Black Bears Polo Club, The Wing was designed by the award-winning architects Spratley & Partners “to follow Bremont’s principles >of aviation, engineering and adventure”, its low-slung curved roof intended to recall an airplane’s wing. The grounds host a red British phone box and the entire cockpit of a Boeing 747-400, which has been used to record podcasts. On the morning I visit, Giles’s yellow 1974 Porsche 911 is sitting in a parking bay. Inside the foyer there’s a navy Jaguar C-Type, a BMW S 1000 RR race bike used to win the Isle of Man TT (Bremont has partnerships with both brands) and a watch boutique. The remainder of The Wing houses manufacturing, assembly, quality control, polishing, packing and dispatch areas, as well as commercial offices and an exhibition of British watchmaking. The public is encouraged to visit and many people do — up to 100 a week. It is the only place in the UK where you may see mass watchmaking in action.

“The challenges of machining watches, this really sums it up,” Giles says, pushing open the door to The Micro Hub, a noisy room with floor-to-ceiling windows containing Bremont’s CNC machines that make the case parts, movement base plates, bridges, gears, cogs and other fiddly elements that make up a mechanical watch.

“A human hair is 70 microns. We’re machining to three microns. We’ll get people from aerospace, Formula 1, the arms industries, who have been working machines all their lives and come and work for us and it blows their minds because they just don’t do it to that level. And you’re doing it with machines that have never been used in the UK before, with unique software and unique programming languages.”

The value of the equipment in this room is said to exceed £25m.

“These ones are really reserved for Rolex,” Giles says, above the squeal of steel being machined. “We’re the only company to have got one outside of Switzerland.”

He doesn’t mean they obtained it via a back channel. He means they are the only non-Swiss company to have ever ordered one.

The offices of the new Bremont CEO are bright and airy and overlook the expanse of the aforementioned polo field. Today, Davide Cerrato is wearing a navy blazer, a stripy blue shirt with a contrast collar, a green tie and slim navy chinos.

It is the middle of the British summertime, and the weather is behaving accordingly.

“Yesterday I was fly fishing,” Cerrato says. “I had booked a fantastic place next to Winchester, and the weather was really like…”

He puffs out his cheeks.

“I was under a waterfall of rain and wind. I looked like I was on a boat in the middle of the Atlantic, fishing for I don’t know what… cod?”

The plan was to speak with Nick, Giles and Cerrato about the next chapter in Bremont’s story. Nick joins in via the speaker on Giles’s iPhone — he’s on holiday in Menorca.

I mumble some apology for interrupting his time away.

“Oh, don’t worry about that,” says Giles.

“He’s on permanent holiday now,” chortles Cerrato.

“I’m surprised I’m still here, as well,” Giles remarks. “Now that Davide’s here.”

“The Union Jack is becoming green, white and red,” says Cerrato.

I ask Nick and Giles why they felt they needed to employ a new CEO.

“Nick and I have been hard at this for a long time,” says Giles. “And we’ve built this foundation and then we raised the funds from our investors, to take us to the next stage of growth. Running a watch business is incredibly complex. You’re a high-tech engineering company, you’re a marketing business, you’re a retailer, you’re a wholesaler, you’re doing it globally, you’re doing it in a country where you haven’t done it before. There’s nothing easy about it. And really, to be involved in this business, you need a left and a right-sided brain. So, to bring someone in who had huge amounts of watch experience made sense. The investors were very keen on it. So we went out on this search [via C-suite consulting firm Egon Zehnder] but Davide felt like an obvious fit.”

“The important thing for Giles and I is to have someone we felt we could work with,” says Nick. “You get these CVs, and you talk to various people in this industry, and people know everyone in this industry, so you find out pretty quickly if they’re a good egg, or just a bit tricky. And what actually have they done? It’s easy to have an elaborate title but, actually, have they relaunched the brand? Have they built a brand from the ground up? Or have they just moved between big luxury groups and haven’t had to get their hands dirty? That was quite important.”

Anyone who knows Bremont knows the brand is Nick and Giles. So how will it work now?

“Davide is definitely leading the show,” says Nick. “And we’re there to help. Giles and I are still out there. If we really want to make this a global company and we want to properly compete with our competitors on a size level, there’s so much more we need to do internationally. And it is impossible for one person to do all that.”

What’s the priority?

“We are working on several points on the communication positioning side,” says Cerrato. “If we want to scale up, it needs to be simplified. So, we are now working on a single narrative around adventure and exploration. Adventure and exploration was born British. It was really made by incredible British characters. And, actually, that fits very well with everything that’s been done, and Nick and Giles’s history is about watchmaking exploration, in setting up something that would have been considered impossible by most people 20 years ago.”

Cerrato’s appointment may also address something fundamental about the Bremont brand. Though it has many committed adherents among sports and dive-watch fans, and many more who buy into its adventure-y aviation ethos, in the era of sneaker drops and hype-watch collabs, there are still more for whom the Spitfire schtick passes over their heads. The cash injection will surely also help with distribution — at present Bremont sells in only a handful of countries. But before that, Cerrato’s job is to make some seriously attractive watches that more people like and can afford. The Black Bay Effect.

“We’re working on something special for land exploration that we will share next April,” he says. “Something that makes the brand stand out. So when people go, ‘Bremont’, they go. ‘Ah yes, one product pops into my mind!’”

Does he know what that product might look like?

“It is not only an idea,” he says, pointing to the bookshelf behind him. “It’s in that folder over there.”

Cerrato has talked of his enthusiasm for the “premium” pricing segment — between £2,000 and £3,000. It is the spot in which the Black Bay launched, and lower than anything in Bremont’s current collection.

“It’s a super-competitive market segment,” he says. “Because the prices are very aggressive and making a super-nice watch for below £3,000 is a big challenge. But it’s the entry segment where new customers get into mechanical watchmaking. We absolutely need to work to position ourselves in that arena to give us chances in the US, which will be our next big market.”

Last year the US was the world’s fastest-growing watch-buying demographic, overtaking China.

“Bill Ackman said, ‘Why are we not competing with the biggest of the big, in terms of size?’” says Nick. “Giles and I have always wanted, when we’ve lost our marbles and are old and grey, to leave a brand that is here to stay. And to do that you put investment in. You can’t just be a cottage-industry brand. You’ve got to go out there properly.”

Is it a good day when someone invests that amount of money?

“Good and bad,” says Giles. “We’re an emotional bunch, and it’s about passion as much as it is making money. My wife always says, ‘Giles, how do you make earning money look so damn difficult?’ And it’s true. It has been blood, sweat and tears to get to this stage.”

The British-underdog angle has worked well in Britain. Playing devil’s advocate, doesn’t everyone else think watchmaking is Swiss?

“It depends, from region to region,” Cerrato says. “Speaking to Americans, they are very open to any brands. And the fact of us being British is our unique, different take. There is really a big opportunity.”

Bremont already has a foothold in America — with its own boutique in New York, and in outlets across the country since 2008 — and it’s not hard to see the Bremont story being embraced wholeheartedly over there. The military connections, the planes and the cars, their backstory. It’s not a total shock to find out that Nick collects first-edition James Bond novels. Their surname, lest we forget, is “English”.

“America is all about the new frontier, isn’t it?” Nick says. “And in an industry where you’ve got several hundred Swiss watch brands all battling for noise, It would have been even harder for us if we were just another Swiss watch brand, 20 years ago. Because everyone is trading on these histories — ‘We’ve been making watches since 1865’, and then you realise, actually, they’ve been dormant for many years of those… We just push that to one side. Just judge us on the product itself.”

There is no bigger expert in product than Rolex. Cerrato spent a decade inside the organisation at Tudor. What did he learn?

“I learned a lot,” he says. “There is a very pure, pristine philosophy about non-compromising, about the ultimate quality for product. And Rolex is probably the strongest place where you have this total dedication to excellence. And that’s a very important learning. Because the product is the pinnacle of everything. If that is super-well done than you can build around it. And then the other one is consistency. Consistency is paramount. If you change every time, everything that you have invested is just thrown away. If you stay consistent, you pile up and up and up, and there’s a tipping point where you become so powerful and monolithic. And that allows the brand to stand the test of time.”

Indeed, Bremont doesn’t really do “trends”.

“With colours, there are some directions [trends],” says Cerrato. “Green is a super-nice colour and it will always be a super-nice colour. If you take purple, which was the big thing of last year, I don’t think it’s going to stay… It’s like the pink Barbie one [a Tag Heuer Carrera worn by Ryan Gosling], it will remain in this year! The pink-year colour!”

You don’t think that one is destined to become a family heirloom?

“No, no!” says Cerrato. “Classical blue, green, the bronze or the gold… or titanium, some innovative material. Definitely yes. Getting something interesting for the long term, that’s the difficult thing.”

On joining the company, Cerrato said that in five years’ time he would be opening a jeroboam of champagne “because we made £60m and 30,000 watches”. Does he stand by that?

“Nothing is impossible,” he smiles.

The last time I speak to Nick it’s late September. He is at home, up the road from The Wing. Today is the last day at work for the current sales director, so he took him out in his 1950s Broussard monoplane. “He came out looking a bit hot and sweaty,” he says. “And slightly pasty.”

Having designed all Bremont’s watches for the last two decades, Nick says he and Giles have been happy to let go and allow Cerrato to do his thing. “We have to step back because it’s just not fair on him. You can’t get someone in like that and just interfere the whole time.”

How does he see Bremont evolving in the near future?

“We have to get a bit more commercial. And a new price point does make sense,” he says. “Watches have gone crazy in the last few years. Partly because the costs have gone up and partly because of greed. So I think you will see a younger demographic.”

He shows me next month’s new release, a new model in their Supermarine dive collection — and the first model Cerrato has been able to “tweak”.

Featuring a bicoloured bezel and pops of colour on the second hand, it’s not quite the Union Jack becoming green, white and red. But you get the idea.

“You can tell from the way he dresses to the detail he goes into on the watches, it’s quite special, actually,” Nick says. “I think he’ll do a very, very good job. I really do.”