If you should ever find yourself, as I did this past September, looking for a guide to the neat suburb of Edgeley, in the steep-sided town of Stockport, Greater Manchester, you could do worse than Terry John. Sturdy, shiny-headed, mile-a-minute gregarious, Terry grew up around here, and it’s clear from just a few hours in his company that while success in his work has enabled him to relocate to a leafier grove, on the edge of the Peak District, he remains a Stockport man to his bones. (To be clear, by “sturdy” I mean that Terry has the approximate dimensions of an industrial fridge freezer; by “shiny headed” I mean bald.)

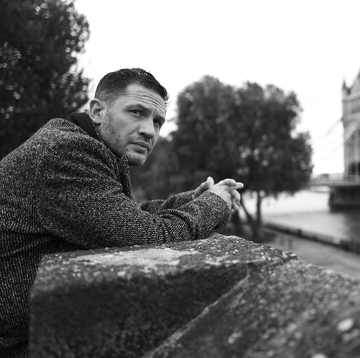

Pristine in his new cagoule and his Tipp-Ex-white trainers, Terry’s patter is an endless scroll of local lore, his smile as wide as the viaduct that dominates the town, his laugh as loud as the trains that clatter across it. Terry has not forgotten where he came from. How could he? He’s still here.

We meet on a Saturday afternoon, under lowering skies, by the elegant covered market. A leisurewear Pevsner, Terry shows off the local landmarks and architectural points of interest: the Tudor façade of Underbank Hall (now a NatWest), the old stone gateway outside St Mary’s church, Robinsons Brewery, the view from the top of Crowther Street, subject of a painting by LS Lowry. He hymns the coming regeneration of the woebegone shopping precinct. He recommends places to eat and drink. Stockport has long been in Manchester’s dark shadow, but to hear Terry tell it, even at this time of political, social and economic crisis, here is a town on the up. A fellow mover and shaker from these parts, the late Tony Wilson, once described his own “heroic flaw” as “an excess of civic pride”. Terry surely wouldn’t go that far, but he’s a persuasive booster for his town. If they had any sense, they’d make him mayor.

It’s Edgeley I really want to see, though, not the historic town centre, for reasons that will become clear. So we jump into Terry’s executive saloon — a deliberately anonymous car, he says, because why draw unnecessary attention? — for the short drive. On the way, we pass the old Strawberry Studios, once owned by 10cc, where Paul McCartney and the Stone Roses recorded. “And Yazoo,” says Terry. “Remember them?” On our left, Edgeley Park, home of Stockport County FC, recently promoted to League Two — another result for the town, says Terry.

A sharp turn into a tightly packed network of red-brick terraced houses, first Grenville Street and then another turn on to Aberdeen Crescent, location of Terry’s childhood home. There it is, number 45, the house Terry was born in. Hardly roomy for two adults and four kids, as they were back then, before Terry’s two youngest sisters came along. But he remembers it as a wonderful place to grow up. We stand at the top of a vertigo-inducing drop, high above Hollywood Park. Terry remembers his mum pushing a pram filled with shopping all the way up the hill from town. This was the 1960s. They didn’t have a car. Hardly anyone did. There was nothing to get in the way of the kids’ street football games.

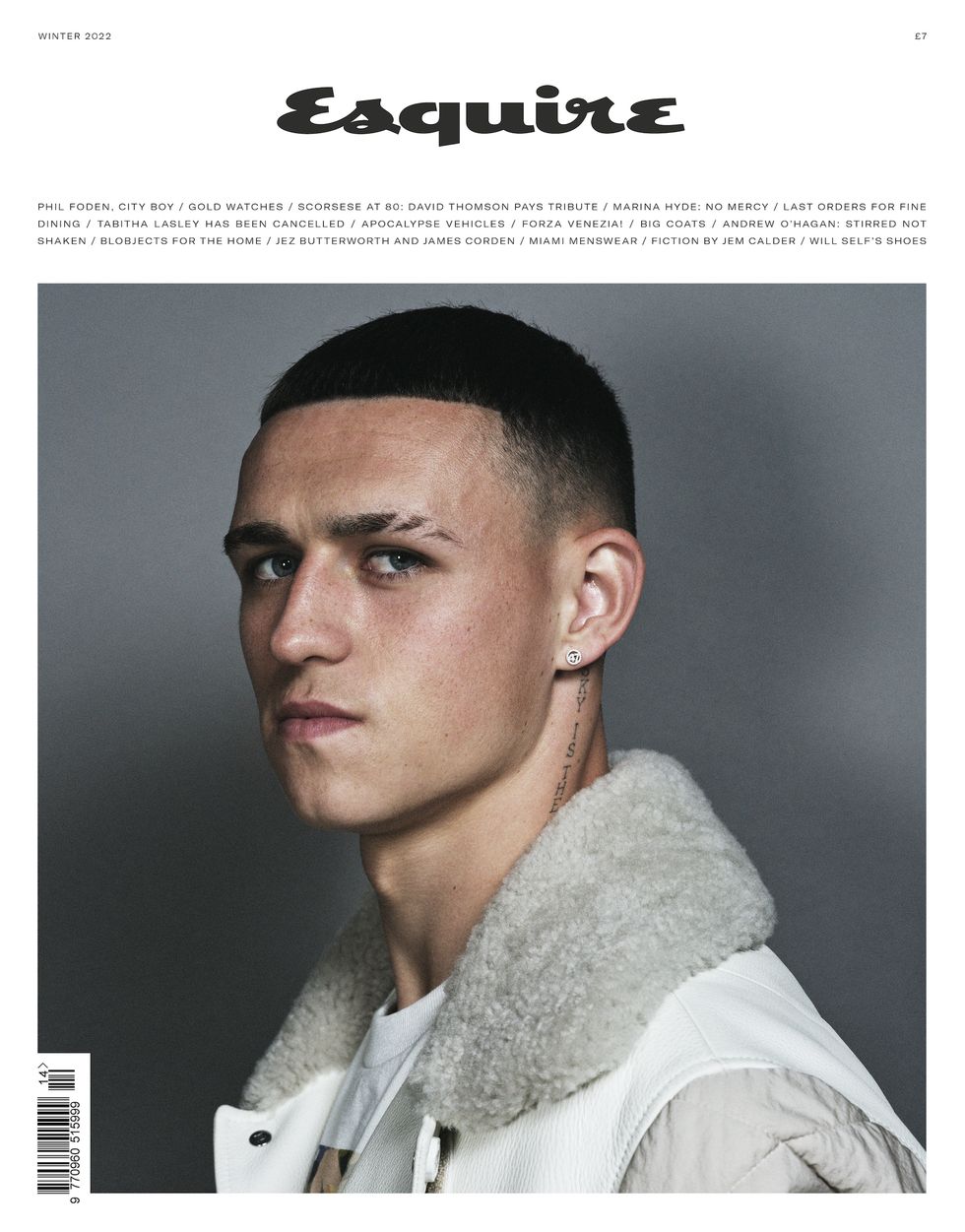

Enjoyable as all this is, we are here for a reason. We are searching for locations for a photo shoot. Our subject is the most valuable discovery of Terry’s many years of scouting and training boys for football clubs. They first met 17 years ago, when the boy was all of five years old. Now he is to appear on the cover of Esquire, in anticipation of his — we hope — starring role for England in the forthcoming World Cup. The idea is to return to the place where it all started, to understand how you get from here (Edgeley) to there (Qatar 2022).

Like Terry, Phil Foden grew up around here, just a corner kick from his mentor’s old front door. He still remembers Terry coming to his primary school, setting up some cones for him to dribble a ball around. Terry must have been impressed, because he gave the boy a card with his number on it, to give to his parents. Foden was invited to take part in sessions organised by Manchester City, and he joined the club’s academy four years later, aged nine. Today, Terry is Foden’s business manager, and the boy has developed into one of the most exciting young players in the world. (Did Terry spot Foden’s potential immediately, I wonder as we drive around? “No, I didn’t have my crystal ball with me that day,” he says. Ask a stupid question...)

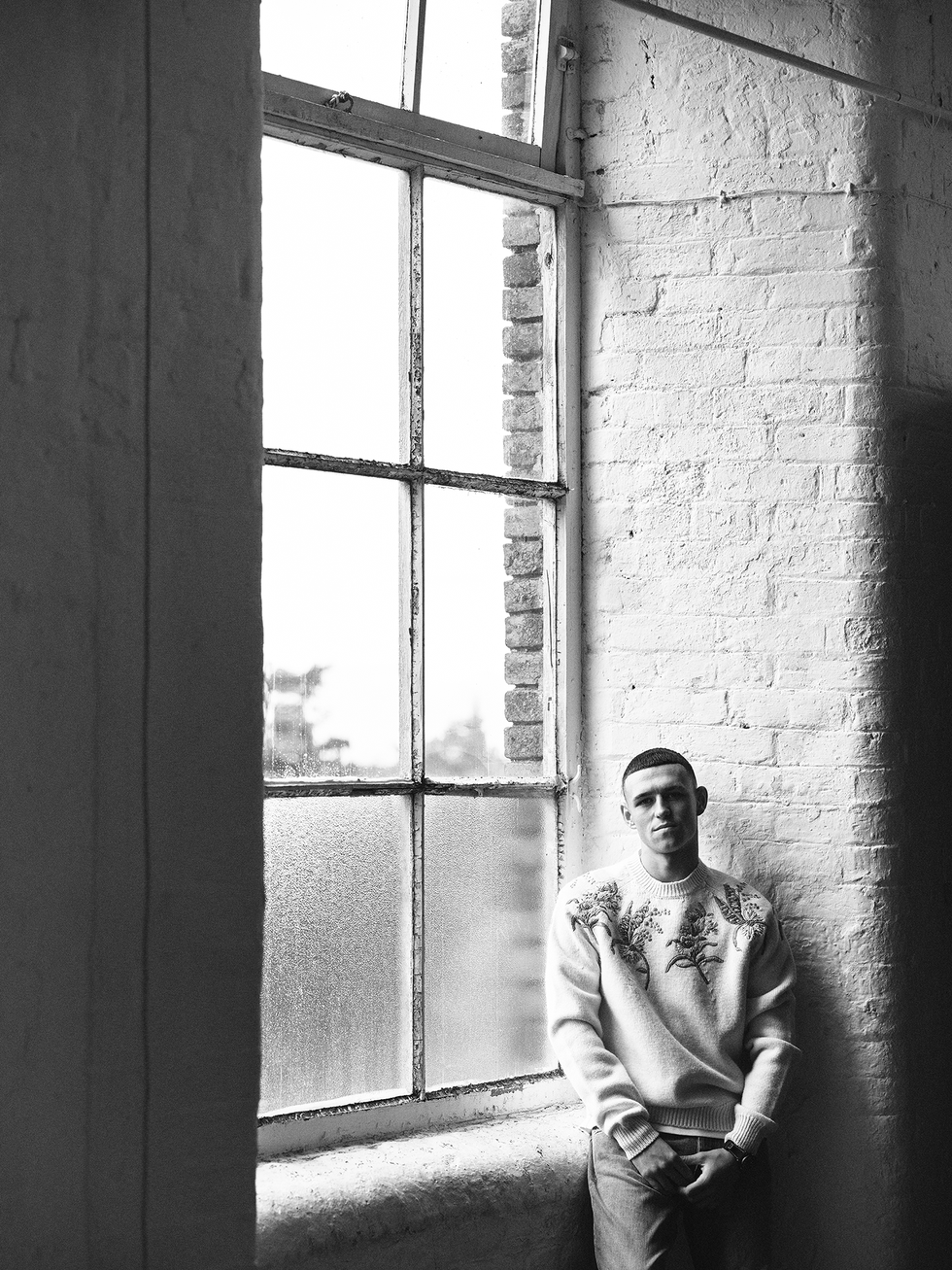

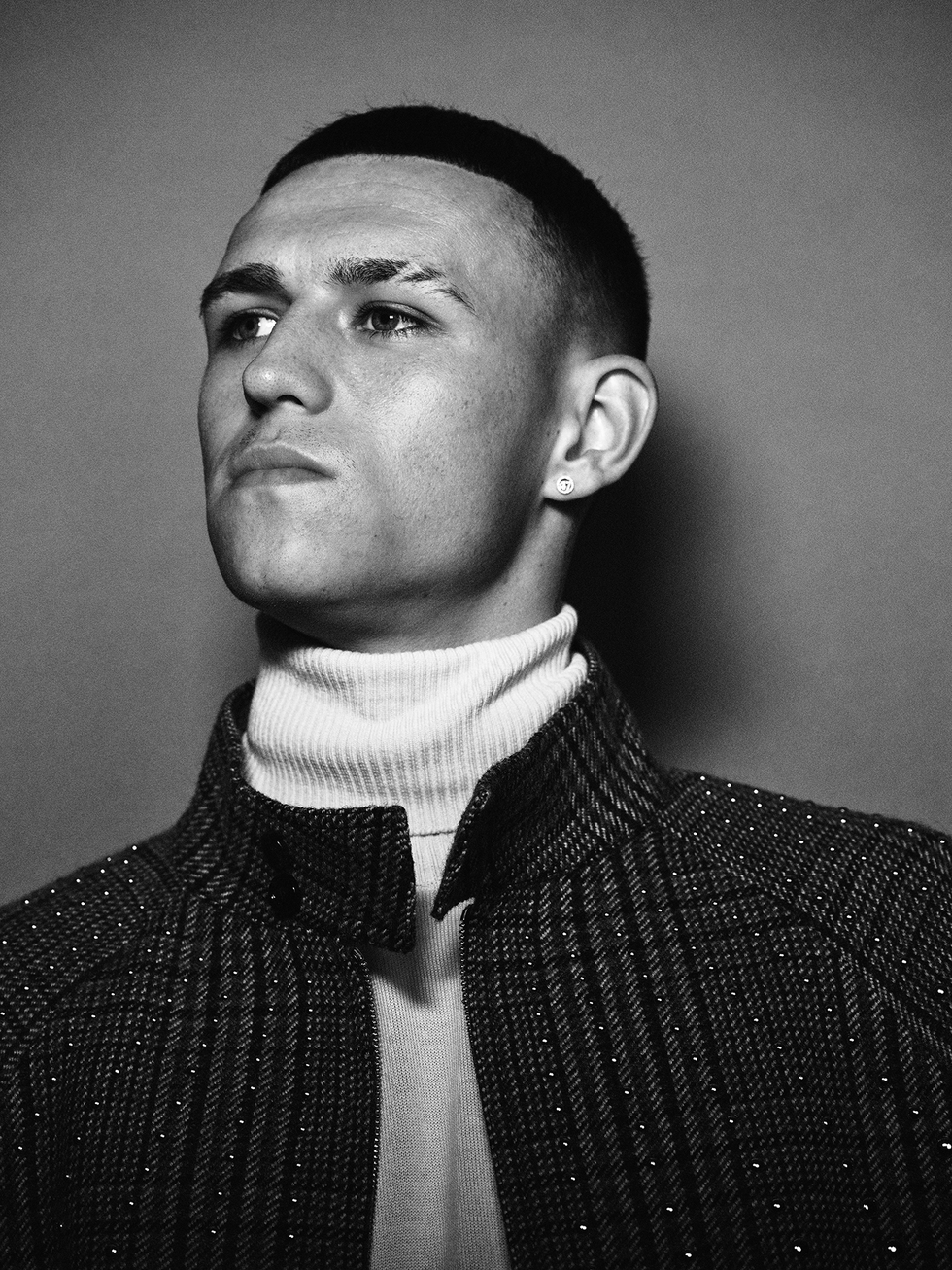

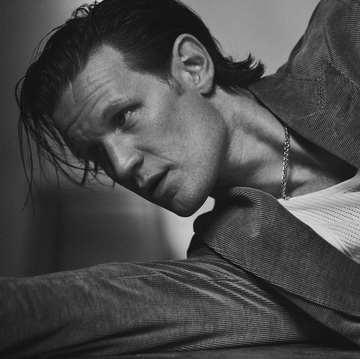

The morning after our tour of Edgeley, a drizzly Sunday, we return with our subject, who has been gussied up in Prada by Esquire’s stylist. As slender as Terry is stocky, as softly spoken as Terry is voluble, Foden appears to be entirely without side, arriving on set with minimum fanfare. (In my experience, this is not always the case with up-and-coming multimillionaire celebrities.) He’s also a good sport, gamely playing keepy-uppy for the camera in the rain, wearing a roll-neck so tight and insubstantial it looks like it might have been picked off the floor of a teenage girl’s bedroom. With his close-cropped hair, his white teeth and his puppyish eyes, he doesn’t look like he’s long out of adolescence himself. Not surprising, really: he’s 22. Only the glinting earring, a circle around the number 47 — his Manchester City shirt number — and his neck tattoo (“SKY’S THE LIMIT”) hint at his fame and status.

I’d been shown Terry’s childhood home the previous day. Now I’m keen to see Foden’s. He leads the way, trailed by me and Terry and the Esquire crew: photographer and assistants and all the others who work to make the pictures look good. And here it is, 117 Grenville Street, opposite the Kingrill restaurant, part of a parade of homes and businesses, some of which have seen better days. He lived here for his first 10 years with his mum, Claire, his dad, Phil Sr, and his elder brother and younger sisters. The house is covered in scaffolding today, and it doesn’t look like anyone’s at home. The Fodens moved away when Phil Jr started at a new school, St Bede’s, in Manchester, the fees paid by City’s Academy. Phil lives in Bramhall now, a smarter suburb of Stockport, just up the road. His parents are not far away. But he comes back all the time, to see his Nana, who still lives on Grenville Street.

Shall we see if she’s in? Maybe she’ll make us a brew. Foden knocks, shouts hello, and then pushes at an open door, revealing a cheerful-looking blond woman, hastily fastening a dressing gown. She offers a sheepish grin. Does she want to come outside and have her picture taken? Does she hell! It’s Sunday morning. She had a late one last night. Gerroff!

Her grandson is delighted by this, the cheeky beggar, and pleased to be able to raise a laugh from the crew. We leave his Nana to her hangover and walk on. I ask him to show us the place where he first learnt to kick a ball. It turns out to be a small car park, on the same street, opposite the William Hill betting shop. As a boy, he says, he would play here with his friends from first light until it was too dark to see the ball. At five and six, he was already running circles around kids three or four years older than him. It wasn’t hard to see he had talent. Everyone wanted him on their team.

Edgeley, as Foden remembers it, was a tight-knit community where everyone treated each other like family. And while 117 Grenville Street was a house divided — Phil’s dad and his brother, Callum, are United fans (“We don’t speak about it”), he and his mum support City — his parents were supportive of his football right from the beginning.

Plenty of famous footballers come from more hardscrabble backgrounds than this. It’s trite to say that it’s a long way from here to the top of the Premier League. Clearly, it is. And then also, it’s no distance at all. Manchester City’s Etihad Stadium is just a few miles away. For Phil Foden, it’s never felt out of reach.

Foden is not the only prodigious young Englishman to be regularly turning heads in the Premier League and beyond. But, to borrow a term from American sports, he is certainly the winningest. With Manchester City, the only club he has ever known, Foden has won four Premier League titles (in 2018, he became the youngest player ever to do so), as well as the FA Cup, the League Cup four times and the Community Shield twice. He has played in a Champions League final. (City lost by a single goal to Chelsea, in 2021.) He has won the Premier League Young Player of the Season and the PFA Young Player of the Year two years in a row (in 2021 and 2022). He made his 100th Premier League appearance in August. In October, he scored his 50th goal for City. That strike was the second of three — his first hat- trick for the club — and it came in the Manchester derby, which City won 6-3.

The stats don’t lie, but Foden knows some of his good fortune is, at least partly, an accident of birth. “My timing was good,” he says, deadpan. The Manchester City that approached him in 2005 was not the club it is today. At that time, City had not won the top division since 1968, the FA Cup since 1969, or any other significant trophies since 1976 (the League Cup). Decades of underachievement followed those glory years, including multiple relegations. In 1998, City went down to Division Two, the third tier, an ignominious fate for such a famous old club.

Everything changed in 2008 when the Abu Dhabi United Group bought City. There are many things to be said about the purchase of English football clubs by the sovereign wealth funds of repressive foreign regimes. But no one can say it doesn’t yield results on the pitch. Since 2008, City have won the Premier League six times, four of those under their present manager, Pep Guardiola, who joined in 2016. With the exception of Sheikh Mansour, Guardiola, the brooding Catalan tactician, formerly of Barcelona and Bayern Munich, is the most significant figure in City’s history since the 1960s. At the time of writing, the team are, once again, favourites to win both the Premier League and the Champions League.

So, Foden reached maturity at precisely the right moment. From his debut, in 2017, he has played for arguably the best club side in the world, under the most gifted manager, alongside some of the finest players ever to have turned out for an English team. If you doubt that statement, consider, from the current squad, the supremely gifted Belgian playmaker, Kevin De Bruyne; the revolutionary Brazilian goalkeeper, Ederson; the Norwegian goal machine, Erling Haaland; and any number of other superstars. (“I know,” he says, as I reel all this off. “It’s crazy.”)

Our interview takes place on the Sunday afternoon. Once we’ve finished taking Foden’s picture on the streets of Edgeley, we drive in convoy to a nearby photo studio, in a converted cotton mill (thanks, Terry), for the more formal portraits. And then Foden and I settle down to talk, in a quiet corner, on some battered sofas.

As is the way with professional sportspeople, whose every recorded utterance is parsed for nuance in the papers and the online forums and on social media, during the interview Foden chooses his words with care, seldom offering two sentences when one will do. Footballers have little to gain from outspokenness, and much to lose.

In the days after our encounter, it’s reported that Foden has signed a new, six-year contract with Manchester City, worth £78m, and that his salary has increased to £250,000 per week. City declined to confirm or deny this when I asked. But for all the insanity of those figures, for the club this amounts to excellent business. At the time of writing, Foden has started every one of City’s Premier League matches this season, consigning older players who cost multiple millions in transfer fees to the bench.

With his whippety physique, Foden would once have been regarded as too slight to make it in English football. But in a Guardiola team, where precision, positioning, invention and versatility are paramount, and exceptional close control is a basic requirement, Foden is a natural fit. He has speed, skill, determination and attacking intent. He seems to glide across the pitch. “Hunger” is the word he uses most often to describe his mentality, and motivation. “I just want to keep winning,” he says. “I want more trophies.”

In the endlessly fluid formations of Guardiola’s teams, Foden, naturally left-footed, has played, in his own words, “every position except ’keeper”. Most recently and regularly, he’s been stationed out wide on the left. And while he enjoys that, and has found much success there, ultimately, like his role model and former teammate, the Spanish midfielder David Silva, he hopes for an attacking position in the middle. (More often than Silva, he is compared to another Spanish midfielder, even more fêted. They call him the “Stockport Iniesta”, a nickname he bridles at. “It’s a nice compliment but I’ve no idea why. He was just too good.”)

Would he say that City’s successes mean more to him, as the only local lad in the senior squad, than to his teammates from Brazil and Belgium and Birmingham? “I think so, yeah. I think it’s extra special for me. I can feel what the fans are feeling because I’ve been there.”

Foden can hardly remember a time when his life wasn’t dominated by his association with Manchester City. He went through every level of the Academy. He did half-days at school, spending afternoons training. (Were there subjects apart from football that captured the younger Foden’s imagination? “PE?”)

By the age of 15, he was ruthlessly focused on a career as a professional. That’s when he realised he was talented enough to go all the way to the top. At 16, during Guardiola’s first season with the club, Foden was training alongside established international stars: Vincent Kompany, Fernandinho, Sergio Agüero. He made his senior debut at 17, coming on for Yaya Touré in the 75th minute of a Champions League game against Feyenoord. His Premier League debut came the following month as a substitute in a 4-1 win against Spurs. Afterwards, Guardiola singled him out for praise.

In the years since then, Foden has become an increasingly influential member of a magnificent team. There were suggestions, a few years ago, that Guardiola should loan him out to a smaller club, as is customary for young players on the up, but the manager made it clear that Foden was going nowhere. Instead, he must be nurtured and protected.

The idea that a young player should stay “grounded” is much repeated in football circles. Foden says there’s never been any chance of him getting too big for his Nikes. His parents took care to shield him, as much as possible, from the madness that surrounds Premier League football, and footballers.

From his teens he was aware, he says, of the size of the opportunity, of how success as a footballer can have life-changing implications not only for the player himself, but for his family and friends. It’s a huge responsibility and presumably something of a burden for a teenager from a humble background. What if he hadn’t made it as a professional?

“Obviously, growing up you do see people around you earning lots of money from playing football,” he says. “I definitely felt the pressure of that. I wanted to be able to look after my family. But my job was just to keep focused on the game. My aim was to just enjoy myself. To play with a smile on my face.”

His reaction to finding himself playing with his boyhood heroes, in front of tens of thousands in person and millions on TV, seems to have been equally phlegmatic. “I thought I was good at ignoring everything,” he says. “In my head it was like, ‘Right: this is the time to show everyone what I can do.’”

Nothing, I suppose, can fully prepare a person for fame, but when it came it seems not to have knocked him off his stride. He remembers the first times he was recognised in the street. “Cars would pull up and people would ask for a photo when I was just walking down the street in Stockport. It was quite strange, getting used to it. But I just try to be respectful and polite.” I wonder how he escapes the cacophony that surrounds the Premier League. The answer is straightforward: he goes fishing with his dad, something they have done together since he was a boy. “It puts my mind at peace.” He uses the time to think about his most recent performances, work out where he went wrong, what he could do better next time, always striving to find a balance between honest self-assessment of his game, which is crucial, and excessive self-criticism, which is counterproductive.

Another thing, apart from fishing, that he shares with his dad: they became fathers young. Foden had the first of his two children with Rebecca, his highschool sweetheart, at just 18.

“It is very young,” he agrees, without elaboration. Has it changed him? “Not at all, I’m exactly the same.” He had experience of helping to look after his younger sisters, he says, so having kids around has not come as a shock.

Most 22-year-olds, I venture, are able to let off steam by going out drinking with their mates. “That’s the hardest thing,” he says. “There’s so much going on out there for a young footballer like myself. The hardest thing is being in bed early and ready to train the next day when there’s all these distractions around. I think that’s where the dedication comes in.” And perhaps being a dad helps here, too? “It keeps me focused.”

Not all talented footballers make it. And even some who do fail to last the distance. They become complacent or find it difficult to cope with the demands of a professional career. “When you’re getting paid so much,” Foden says, “and you’ve got everything you want, sometimes it’s hard to feel the same hunger. That’s what I feel, looking from the outside at certain players.”

Remarkably, to my mind, having once been an easily distracted young person (perhaps you were one once, too?), Foden has blotted his otherwise spotless professional copybook only once, in public. In Iceland in 2020, two days after having made his senior international debut, he was fined and withdrawn from the England squad, having breached the FA’s Covid-19 isolation protocols. Phone footage posted on social media showed him and a teammate, Manchester United’s Mason Greenwood, entertaining local girls at their hotel. There was no suggestion that anything untoward had taken place, only that team rules had been broken.

Does Foden think footballers get a hard time from the media? “Yeah, I do,” he says, “and I think it’s getting worse. I think the younger generation are all wrapped up in their phones, in social media.”

He’s not a fan of social media. “I find it boring,” he says. “There’s too much negative stuff. A lot of people who don’t know anything about football. I just ignore it, it’s not for me.”

Fortunately, whatever happens off the field, the place where he is happiest is at work. “Once I step on the pitch,” he says, “everything else just goes away. Whatever is going on in my life, it disappears. I think some players struggle with [all the distractions], but not me.”

“I just love football,” he says, when I ask why that is. “Nothing can ever get in the way. When I wake up, I can’t wait to get to training. I don’t think that’ll ever change.”

In November, all being well, Phil Foden will travel to Qatar with the England squad for the World Cup. At the time of writing, if form is a guide, he has every chance of starting the opening group matches, against Iran, the USA and Wales.

Foden has already won a World Cup for England. In 2017, he was the star of the team that won the Under-17 World Cup, in India. In the final, a 5-2 victory over Spain in Kolkata, Foden scored twice. He won the Golden Ball for the best player of the tournament and was voted BBC Young Sports Personality of the Year as a result.

In the delirious summer of 2021, Foden was part of the England squad for the Covid-delayed Euro 2020. He caught the eye straight away by appearing for the first game, against Croatia, with his hair dyed bottle-blond, apparently in homage to Gazza, Euro ’96 vintage. (Like many, I’m sure, I made a deal with my son—he was eight at the time — that if England won, we’d both do the same, in homage to Foden, Euro ’20 vintage. Sadly, or perhaps not, it wasn’t to be. But we came perilously close to breaking out the bleach.)

Foden admits to mixed emotions, looking back on his first major international tournament. While it was thrilling to be swept up in the excitement, for him personally the Euros were a letdown. Having started the early group games, he was on the bench for England’s knockout wins against Germany and Ukraine, and while he came on for extra time in the semi-final victory against Denmark, he missed the final entirely.

He describes the moment it all went wrong, on the eve of the match against Italy, at Wembley. “[I was] just walking in from training and someone’s passed me a ball and I’ve decided to do a stupid touch and gone over on my foot. I felt a crack in the top of my foot and I couldn’t walk. I knew straight away. The full world was watching, talking about the final, and here’s me got injured just before probably the biggest game of my life.”

In some respects, I suggest, that injury might be seen as a blessing. Quite apart from the enervating disappointment of the match itself — England’s early goal followed by the crushing inevitability of the Italian equaliser, the trauma of the penalty shoot-out, Italy’s eventual triumph — the occasion was disfigured by crowd trouble before and after the game, and the revolting racism aimed at the three England players who missed penalties: Marcus Rashford, Jadon Sancho and Bukayo Saka. All (or at least, many) of English football’s most shameful and appalling characteristics on show in one night of bathos. Who would want to be part of that?

But Foden is having none of it. “Gutted, mate,” is his typically pithy summary of his feelings about missing out. “Never felt like that before.”

A frequent observation made during Euro 2020 was that, at least until the final, manager Gareth Southgate’s young team were playing with an energy and even a joy that had been absent from the national team’s performances for years. The hysteria that surrounds the England team; the inflated expectations, from press and public, that have stifled its players for generations; the constant rehashing of past victories and defeats (especially defeats); the exaggerated sense of England’s own centrality to the story of the world’s favourite sport; the recriminations when things go wrong; the sense that somehow we have a divine right to win... at last, the story went in the summer of 2021, all that had been laid to rest.

Foden says he couldn’t believe the level of attention on the team at the Euros. But he agrees that his generation of footballers is less likely to feel the dead weight of history on their shoulders every time they pull on the shirt. Not only was he not born in 1966 (and neither was his dad), he wasn’t born in 1990, either, when England lost on penalties to Germany at the World Cup, nor in 1996, when England lost on penalties to Germany at the Euros. And at the most recent international football tournament, the women’s Euros, in July, England won! So what’s with all the doom and gloom?

The England men’s performances since the Euros have not been encouraging. At the time I met Foden, England’s five games since June in Uefa’s not-much-loved, or even much- understood, Nations League competition, had produced two draws and two losses. The losses included a 4-0 defeat to Hungary, in Wolverhampton, the worst home result in 94 years, as the papers delighted in reporting, during which team and manager were loudly booed.

The week after our interview, England lost again, to Italy (also again). Foden and the teenage midfielder, Jude Bellingham, were widely identified as the only two players to have acquitted themselves well. There were more boos and, idiotically, calls for Southgate to be sacked. Then England played Germany, at Wembley. Foden was withdrawn after an hour with the Germans a goal up and to the sound of knives sharpening. The final result was 3-3, so disaster was averted, and the prospect of months of doomy introspection from the football commentariat, in the lead-up to the World Cup, was mercifully avoided.

For all these recent tribulations, England are still second favourites to win the World Cup, after Brazil. It’s this kind of silliness, one suspects, that piles the pressure on, just when the team need it least.

Does Foden think it is a realistic assessment? “How is it decided, that?”

By the bookies, I tell him. He all but snorts.

“There’s so many quality teams. Any one of them can win the World Cup.”

Can England?

“Definitely.”

I have to ask these questions, he has to answer them.

Or not. It is perhaps illustrative of sensitivities around international football that while he’s never exactly expansive, the only time Foden becomes evasive is when it comes to talking about the World Cup. Specifically, Fifa’s decision to award the right to host it to Qatar, not a country that one could describe as having a rich history in the competition. (They’ve never qualified before.) Nor a state that ranks high on the list of freedom-loving, socially liberal, open and tolerant societies. (It’s ruled by an autocratic hereditary monarchy with an abysmal record on human rights.)

Not inaccurately, Foden points out that Fifa’s decision has nothing to do with him. It’s true that he was no more consulted on it than I was. Neither is it the players’ fault that Fifa has elected to hold the tournament for the first time during the winter, so cutting the domestic seasons in Europe and elsewhere in half. (That part, Foden will concede, is “weird”.)

Still, I wonder what sort of atmosphere he is expecting to find in Qatar?

“Don’t know ’cos I’ve never been.”

Invited to speculate on his own role on the field (I’d asked if, in the event of a shoot-out, he would take a penalty), he is equally coy.

“Don’t even know if I’ll go to the World Cup, to start with.”

I tell him we are all very much hoping that he will go to the World Cup.

“You never know what can happen, do you? Injuries, selection...”

Please don’t get injured, I tell him. It’ll ruin our whole Esquire World Cup special.

“How can I say if I’ll take a penalty if I don’t even know if I’m going yet?”

OK. In a hypothetical situation, if he was in the England squad and picked for the final and he was on the pitch after extra-time and there were to be a penalty shoot-out, would he step up and take one?

“Yeah,” he says, sticking out his chin.

We leave it there. A warm handshake, no hard feelings, everyone doing his job.

“Thank you, mate,” says Foden, earnestly.

Terry’s going to drive him home to Bramhall. Rebecca is waiting with the kids. They’ve made plans to spend the afternoon with friends. And so this ordinary young man with extraordinary ability puts his jacket on over his hoodie and makes a quiet exit.

My train to London doesn’t leave for a couple of hours. I decide to walk to the station, along Wellington Road, the windswept main drag, then left into Greek Street and back to Edgeley, for another nose around. On the corner of Chatham Street and St Matthew’s Road, opposite the church, there’s a boy, maybe seven or eight, in a grey tracksuit and dirty trainers. He’s kicking a football against a red brick wall, over and over again.