In October 2011 I was at Stansted Airport with my wife — the journalist and editor Georgina Henry — and our two children for an early flight to Berlin, where we had rented a flat for the half-term holidays. Georgina ducked inside a WHSmith’s and bought an armload of newspapers. This was before the internet had transformed our consumption of news, and the week before the first season of Top Boy was due to air on Channel 4. I was excited, about Berlin and the show.

We boarded and settled into our seats. Georgina started to go through her reading with the speed and ruthlessness of a seasoned newspaper professional, turning the pages swiftly, her practised eye scanning for items of interest and moving on quickly if she couldn’t find anything. Then she said, “Have a look at this,” lifting that morning’s Times to show me a double-page spread on Top Boy by Andrew Billen, then the paper’s TV critic.

Writers learn from the school of hard knocks not to get our hopes up. Before launch, you might think what you’ve produced is different and special and amazing. Everyone involved in the production might think the same. You have a good script, a great director, brilliant cast. Of course it’s amazing.

But then comes the acid test. The thing comes out. There can be maverick reviews and unfair crits, but, as a rule, movies, novels, plays and TV eventually find the right level. Most are not bad. But most are mediocre. It’s painful — I’ve been there — given all the hard work and the creative and intellectual commitment involved, but it’s true. Most cultural output will be quickly forgotten.

But the buzz about Top Boy was positive and growing. Word was getting around. This show was different. Reading Billen’s piece on the plane to Berlin, I allowed myself to be hopeful. Maybe I’d written a hit, although it all seemed so unlikely. It was a decade before Black Lives Matter and #MeToo. Getting a show with a 90 per cent Black cast and no big stars to screen had been a struggle. But here it was, undeniably building momentum in the lead-up to transmission. I couldn’t have been happier.

Back in 2011, I had a Blackberry. It was pink and the object of much amusement to my friends. The salesperson had suggested I wouldn’t want a pink phone. It was at a discount so I took it. And I really liked it. Landing in Berlin, I turned on my pink Blackberry. It immediately flooded with messages. Obviously friends and colleagues had seen the Times article and were texting their congratulations and excitement. The holiday was starting well.

But wait a minute. What?

The texts had nothing to do with Top Boy. Instead, friends were asking if I was OK? They were telling me that they’d heard on the BBC news that police in the north of Ireland were investigating me, for murder.

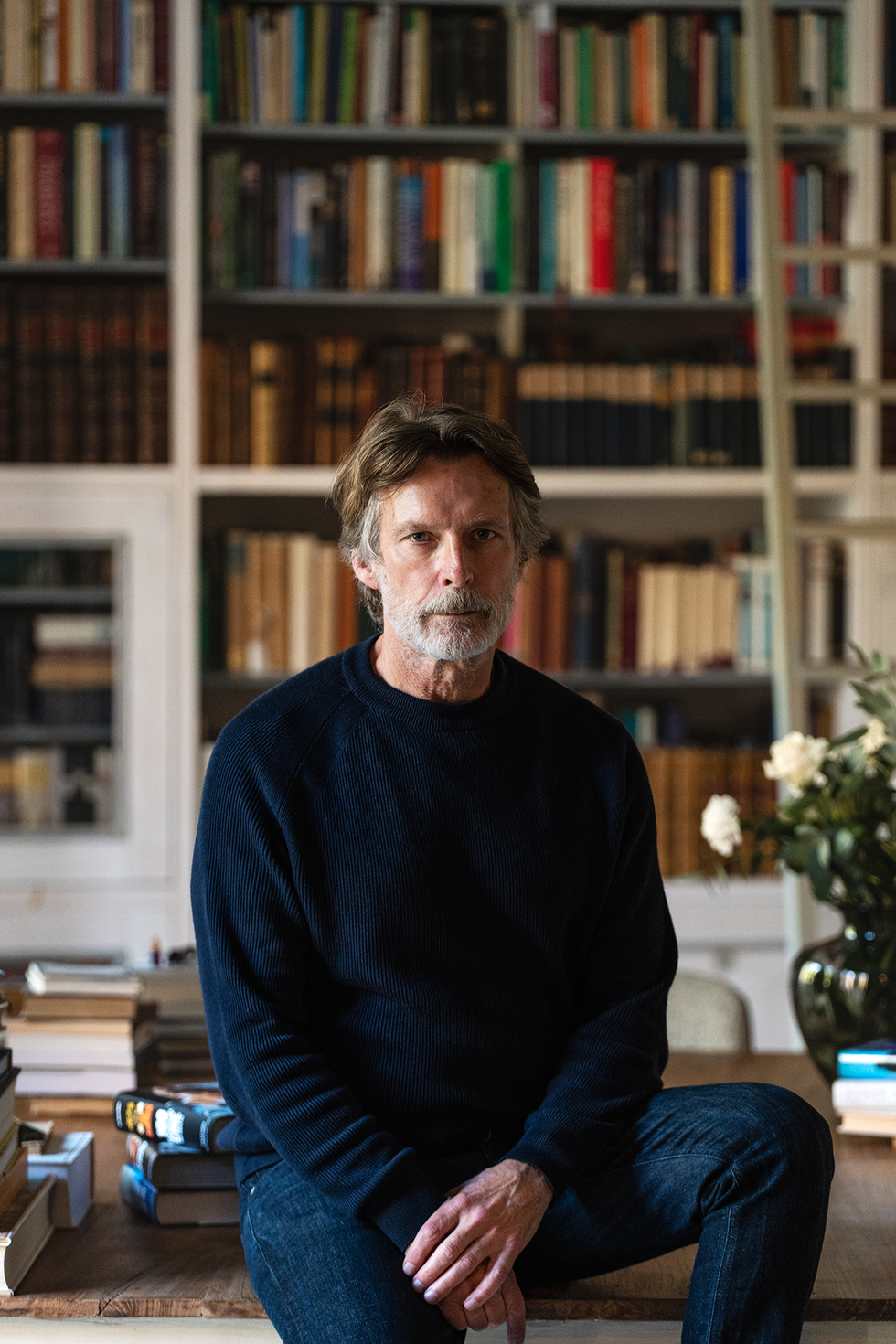

The saying goes that writers write about what they know. It’s true, up to a point. But it’s also a lot more complicated. My first novel, The Second Prison, came out in 1991. My first piece for screen, Love Lies Bleeding, appeared on BBC2 in 1992. I’ve been doing this a long time and I’ve thought a lot about it. I would say it’s not so much that writers write about what they know and more that we are in a continual process of absorbing, using, chasing, losing, misplacing, misremembering, reabsorbing, and constantly trying — and usually failing — to make sense of our own experiences, and then exploring them in different forms of fiction.

It’s so much more inchoate, random and treacherous than simply writing “what you know”. Writers are just as likely as anyone else to be mystified by experience and memory. After all, we’re not talking about logic here. We’re talking about things that seem somehow always just beyond our grasp and resistant to definition. The Spanish poet Lorca talks about the duende: the imp, the spirit, always fighting intellectual deconstruction, variously mischievous and unreliable, tantalising and infuriating. Even after a lifetime of processing the psychological and emotional impact of memory and experience we’re never really sure what they amount to. But they are what make us who we are, whether we’re a programmer, a courier, a midwife or a writer.

My youthful experience of arrests and periods of imprisonment in the 1970s arising out of the Troubles was not unusual in the Ireland of those years, and by no means the worst. Occasionally, friends from those days will tease me: “Ronan, you were hardly in long enough for a shower, a shave, a shite and a smoke.” Now, the details of what happened are less important to me than how they’ve left me feeling. Imprisonment, along with parenthood and bereavement, are the defining experiences of my life. I’ve been asked more than once would I have been a writer without them? All I can say is that if I had not gone to prison, I would have been a different writer.

I’ve been arrested by police, Special Branch and British soldiers, so I know what arrests are like. I’ve been in a prisoner-of-war camp — Long Kesh, the hastily built camp for Irish republican internees on the outskirts of Belfast, resembled nothing so much as the kind of German prisoner-of-war camp depicted in the movie Stalag 17 — and I’ve been in the more familiar old-fashioned Victorian prisons. I know what prison is like. I know what interrogations are like, that climactic showdown between predator and prey. There are interrogations of one form or another in pretty much everything I’ve written: the movie Public Enemies, the TV series Gunpowder, the novels The Catastrophist and Havoc, in its Third Year, and many more, including Top Boy (Dushane in season two). Any writer can research what an interrogation looks like and recreate it convincingly and maybe even brilliantly, but the visual information, the sounds and the dialogue particular to this world are only part of its dramatic recreation, and not even the most important part.

Without even being aware of the processes working on me, what I saw and what I felt in police stations and prisons was, from an early age, taking my imagination in a certain direction. I was becoming curious about what the world looked like from the point of view of the outcast, the criminal, the socially marginalised, the distrusted, the despised, the overlooked. The American socialist and activist Eugene Debs wrote: “Years ago, I recognised my kinship with all living things, and I made up my mind that I was not one bit better than the meanest on earth. While there is a lower class, I am in it, while there is a criminal element, I am of it, and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free.”

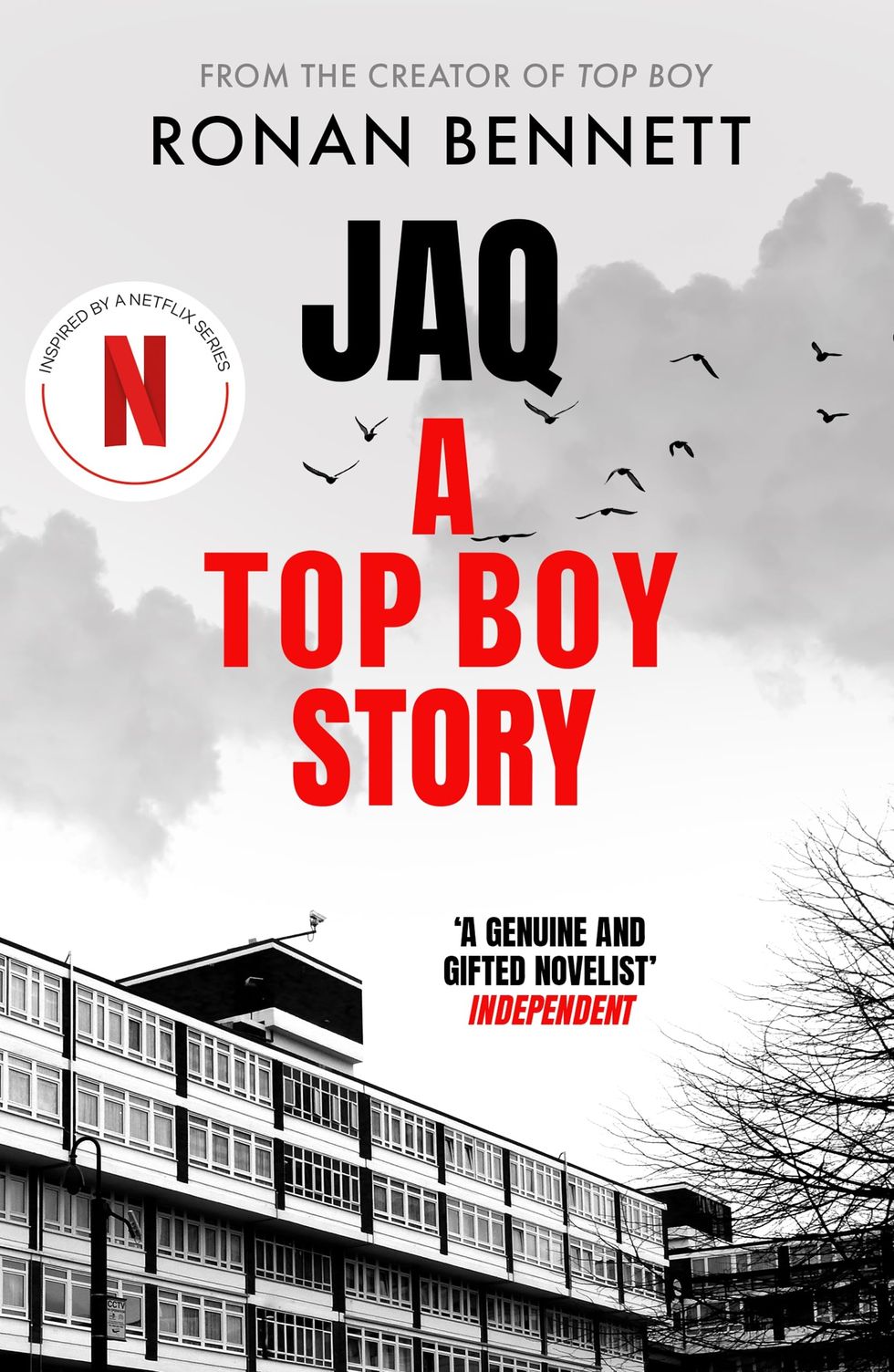

When I first started to experiment with fiction at the beginning of the 1980s, the memory of prison was still fresh, and these lines exercised a powerful hold over my imagination and loyalties. I distrusted authority and institutions; I sided with Debs. The protagonist of my first novel, The Second Prison, was a prisoner trying to make sense of the worlds inside and outside the walls, not because of what I had seen, but because of what I felt. It’s about sensibility, not information. The protagonist of my most recent novel, Jaq: A Top Boy Story, will be familiar to fans of the TV series: Jaq, a young woman drug dealer relying on her wits to survive in a sea of very deadly sharks. This is the world my imagination inhabits. To paraphrase Debs, I’m not one bit better than any other writer. My world has no more validity than any other’s writer’s world. But it is mine. It’s what I write about.

So, when one morning in 2009 I saw a boy of around 10 or 12 dealing outside my local Tesco in Hackney, I was naturally curious. I wanted to know his story, what he was doing there, what his life was like, what he wanted. I approached him. He thought I was police. I told him I was a writer and just wanted to talk. He asked for money. I said no. He walked off, and as far as I know I have never seen him since. I hope he’s avoided jail. I hope he hasn’t been shot. But I have no way of knowing.

Gerry Jackson and I have been friends for a long time. Gerry, from a Jamaican family, is a hugely popular and respected figure in Hackney, and I knew I had to talk to him about this kid. Gerry put me in touch with a couple of “top boys”. I’d only ever heard the phrase “top boy” in connection with organised football hooliganism, but here it had another meaning; “top boy” stayed with me and became Top Boy. The second Gerry uttered those words, I knew I had a title.

Through Gerry, I talked to a number of top boys and roadmen. I don’t like the word “interview” in this context — too formal, and kind of patronising. We talked over coffee and beers, not just about life on the road but about families, clothes, work, school, fears, dreams. Very quickly I realised I had gold. What to do with it?

For a screenwriter, the choice of who to approach with your idea is critical. Preferably, you want someone who has weight in the industry and who also understands your outlook and sensibility. I called my friend Stephen Wright, also from Belfast, at BBC Drama. We’d worked on a couple of things before and I knew he would get what I wanted to do. Stephen spoke to his boss Patrick Spence, and within a few days I was sitting in their office at Television Centre. In those days, before the stifling centralisation of BBC drama commissioning, commissioners like Stephen and Patrick still had some autonomy. A single feature-length script for television was commissioned soon after. Talent was trusted.

I was pumped, and finished the script quickly. Inspired by a real event, I ended the film with Sully — later to be embodied by Kane Robinson as one of the two gang leaders building up their drugs empire on the fictional Summerhouse estate — racing on a motorbike into London Fields to kill a rival. In the actual incident, the only person who got shot was an unsuspecting picnicker. The chaos of the real thing made an impact on me. Whenever shots got fired in Top Boy, I always insisted that it should be messy; our characters — like their real-world counterparts — are not trained killers. They have not practised on the shooting range. They get up close and fire wildly. Even though they get better at killing as the series develops, they’re as likely to miss as hit, and it’s more likely to go wrong than right. My film would be real, not slick.

I’ve worked with many TV and film executives who are excellent people and really good at their jobs. I’ve also encountered idiots. I didn’t think the head of BBC drama at that time was very good. It wasn’t just that he didn’t like the script, he didn’t get the world it was set in. Whatever his formative experiences had been, they hadn’t led him to any kind of curiosity about the people who inhabited Top Boy.

I like being in rooms with people who know more than I do. It’s like playing chess. You learn more from stronger players, even if you lose. I really do not appreciate being in rooms with untalented people who think they know more than you do. He flailed around for something to say. “The language is a problem,” he pronounced. “We can’t have the word ‘milf’ on the BBC.” This was some time before Fleabag. Maybe I could make the characters more likeable?

Sign up to Junk Mail, our ruthlessly edited weekly digest of the very best the entertainment industry has to offer. Each Friday lunchtime the Esquire team will recommend a small selection of films, books, TV shows, music, theatre and more that we think are truly worthy of your attention.

Make the characters more likeable? I’m trying to create someone memorable and complicated. I don’t care whether you like them or not. Is Lear likeable? It’s the one note guaranteed to sour my mood.

The head of drama looked at his phone. He had more meetings. He sighed wearily. He said, “Do you ever have one of those days when you want to throw yourself out the window?” No, I replied evenly, but I do have days when I want to throw other people out the window. He laughed uncomfortably and suggested I do another pass at the script. This is often just a sop to the writer, a way to sweeten the bad news and keep a flicker of hope alive. He got up and left. Stephen and Patrick asked if I would write another draft.

Even though I knew my script would never be greenlit at the BBC, I could not bear to think of having to start all over again to find another home for Top Boy. I would also get paid.

I still feel ashamed of the subsequent draft. It wasn’t what I wanted to write. Even as I delivered it, I knew it wouldn’t get made. I’d abased myself for nothing more than a second-draft fee. And, sure enough, the head of drama duly passed. Stephen and Patrick were disappointed but not surprised. (Both remain active producers, though neither works for the BBC today.) I shrugged and went on to the next project. That’s the way the industry works.

Top Boy was dead.

New agents work very hard for their new clients. They have to. They need to build their reputation, they need to build confidence and trust and to show the client how active they’re being. My new agent, Charles Collier, set up meeting after meeting. They’re called “generals”. Everyone does them, actors, directors, writers. Generals very rarely result in anything concrete in the immediate or short term but can sometimes be useful as a way to find and make connections with like-minded souls in the industry. They can also be humiliating, especially the ones in LA when you turn up at an office where everyone you meet takes you by the hand, looks you in the eye and tells you hand on heart that they are a “huge fan” of your work. You leave with sincere protestations ringing in your ears that this is just the beginning of what will be a brilliant creative relationship, and you never hear from them again.

After dutifully attending several generals arranged for me by Charles, I was done. However, he urged me to meet producers Charles Steel and Aly Flind of Cowboy Films for lunch at the Groucho (where I never go). Charles and Aly had had a hit with The Last King of Scotland (2006), the Oscar-winning film about Idi Amin. In film and television, you can live off the fat of one success for about five years. That’s the time to make hay. Charles and Aly were keen and full of energy.

I don’t have a lot of small talk and I don’t have any industry gossip because I’m not interested in how the industry works or who’s who, so we chatted generally about this and that. It turned out we had similar tastes, but it wasn’t until near the end of the lunch that I mentioned my disappointment over a project called Top Boy. Charles and Aly liked the sound of it and asked to read the script. My agent sent them the first draft I had written for the BBC.

Within a month Charles, Aly and I were in the office of Liza Marshall, then Channel 4’s head of drama. Liza liked the script and was going to talk to Jay Hunt, the Channel’s chief creative officer. Very soon afterwards, in the summer of 2010, we were greenlit for a four-part series. Top Boy wasn’t dead after all, but I was going to have to rethink the shape and content of my original feature-length script, and write a further three more hour-long episodes.

There is nothing more incentivising for a screenwriter than the fabled green light. Actually, you rarely get a definitive green light, the starting pistol for production; it’s more different shades of amber, a process rather than a single event. But however it comes, the promise of production means you’re not writing into a potential void. What you write will see the light of day. It’s something to celebrate.

But the green light also brings its challenges. It’s when the rubber hits the road.

Iswas. This is how I describe the beginning of every film and television project. It Starts With A Script. ISWAS.

In the early stages of development, the writer is god. You’re the creator. The writer has breathed life into the characters. It’s your story, your voice, your world. Except, as the scripts are delivered and preproduction ramps up, you have to share your creation.

People often ask, How much control do you have? For the last 15 years, I’ve produced — often through my company Easter Partisan Films — as well as written my own material.

Even so, it’s not a question that makes any sense to me. “Control” is not a concept I recognise in film and television.

If you search a title on IMDbPro, click on the tab for “Filmmakers”. You’ll see just how many people are involved in making a TV show or film. And they will all have opinions. That’s their job. The producers, the director, production designer, director of photography, hair and make-up, casting director, music supervisor, editor... And that’s not to mention the cast. It’s a long, long list. They are all voices in the room.

Someone once said something like, Anarchism is OK, as long as I’m the anarch. Collaboration for a writer is tricky to negotiate. The experience varies from project to project and it depends in large measure on the personalities, status, expectations and working practices of your collaborators. I like teamwork; I also have to admit that I like being the anarch. The two impulses are in constant tension, but not necessarily irreconcilably so. It helps if you rate the people you’re working with. Equally, they need to know how to work with writers. Mutual respect is key. Entering into a respectful creative discussion is exciting. Telling a writer what to write is going to get unpleasant.

You’ll like some of your collaborators and dislike others. Some will have more weight and be more present than others. Some will be better at putting forward their ideas. Some will be more adept and political at manoeuvring in order to get their way. Some will have terrible ideas. Some will be unbearable human beings, insecure, histrionic and impossible to deal with. Some will have great ideas and be good at working collaboratively. They’re a joy.

If you’re not prepared to relinquish the god thing and get down into the dirt as a mortal rewrite-man/woman, don’t even think about trying to write for screen. It’ll break your heart.

I’m a compulsive rewriter of my own work. My process is to throw down the first draft as quickly and in as uninhibited a way as possible. I’ve seen this referred to as the “vomit draft”. Inhibition is the enemy of creative writing. The English novelist John Braine (Room at the Top) had “Get something down” Sellotaped to his typewriter. Let it all out, is my view, let it flow. Then craft it. And craft it again. In chess, you’re taught that if you think you’ve found a good move, look for a better one. Same with writing. If you think you’ve found the right word, look for a better one. But be warned: the notes are going to come in thick and fast. If you can’t deal with notes, stay in your garret and write your poetry.

I usually have a rough idea of the ending when I start work on a new script or novel. But I don’t necessarily know how I’m going to get there. Every writer has their own process, but for me there’s a lot of discovery involved as the pages are written and rewritten. This only works if I feel I am writing with the backing of my collaborators. Writers need to feel trusted and empowered. Confidence is key. Writers need to be allowed to fly.

Unfortunately, writing for screen has become more and more bureaucratic. Notes, especially with bigger-budget projects when big money, reputations and executives’ jobs are on the line, tend to become more aggressive. It can be demoralising and undermine the confidence needed for creative writing. I receive far more notes now than I did when I started 30 years ago. Development executives increasingly crawl all over the scripts. Their job should be to encourage and enable. Instead, too often, the scrutiny descends to the pedantic, and it can become writing by committee. Film-making, one of my agents says, is the only business in which people with no accomplishments are permitted to tell people with a lot of accomplishments what to do.

Sometimes an exhausted writer will take the line of least resistance and acquiesce to notes they know are wrong. Walking the collaborative line isn’t easy. Give too much ground and you’re a hack. Dig in intransigently and you might be shooting yourself in the foot.

In the old days, a writer would think of an idea, take it to a producer, be paid to write the script and effectively become a hired hand on their own project. The writer would take a writing fee, the producers would take ownership and profits. This started to change a decade ago with the advent of the streamers and the huge increase in demand for content because... well, ISWAS. More and more writers started to become producers of their own material. Producers had little choice but to accept the new reality and transition from an employer-employee set-up to a partnership in which ownership and profits are shared.

When I took Top Boy to Charles and Aly at Cowboy, Charles Collier was adamant it would only be as a partner, not as a writer for hire. It was one of the first deals of its kind made in London. Now it’s the norm, and producers know that they have to cultivate relationships with writers (and other creatives) because without them, they have nothing to take to market.

This did not give me “control” — I’ll say it again: such a thing does not exist in this industry — but it did mean that my voice in the room was that little bit louder.

I still urge new writers to go into the collaboration open to good ideas. Holding on to your vision is not the same as intransigence. Film-making starts with a script, but it doesn’t end with a script, at least not only a script. A small army of (mostly) talented people will have had their input. With luck, no one will have had to shout because, with luck, everyone is trying to make the same film or show.

Luck plays a part in everything in life, and Top Boy had an incredible stroke of luck because, just as Channel 4 greenlit us, I was spending a week as a mentor at one of Robert Redford’s Sundance screenwriting workshops, in Jordan. A young writer/director had come along with a script he’d called Father. His name was Yann Demange and he was getting a lot of well-deserved praise for Criminal Justice, which he’d directed for the BBC. Yann and I connected on the workshop. With his background — mixed heritage, raised in care homes — I knew he would be a perfect fit for Top Boy. Back in London, we arranged to meet Charles and Aly. Channel 4 was delighted to have him direct the series.

With the director on board, everything started moving very fast. Des Hamilton came on as casting director. Des, from Glasgow, has a very particular history and it has led him to a sensibility not unlike my own. He was already interested in grime music and found a mesmerising artist called Kano who had never acted before but he thought would be good for Sully. He suggested Ashley Walters, of So Solid Crew, for Dushane, Sully’s best friend and rival for the title of “top boy”. Ashley’s own experiences of gangs and prison meant that he was familiar with the Top Boy world. Des also liked to find actors on the streets. Gerry and I were showing Des and Yann around a housing estate in Hackney when we bumped into Gerry’s cousin Shone Romulus. Des and Yann spotted Shone’s potential immediately and arranged for him to audition. Shone became Dris, bringing authenticity, charm and a kind of laid-back menace to the role.

Casting continued apace. We crewed up. I had the four shooting scripts ready by February 2011.

Time to go back to Berlin during the October 2011 half-term holidays.

And the murder investigation.

ver the course of the first two or three days of our half-term holiday I was keeping an eye on developments in Belfast. Several people had been arrested. The murder inquiry related to the shooting of a police inspector during an IRA bank robbery in 1974. Aged 18, I had been arrested and charged a month after the killing. A year later I was convicted in a no-jury Diplock court and sentenced to life.

I had nothing to do with the bank robbery or the murder, but back then it was conveyor-belt justice. The courts were rammed, standards of evidence were laughably low, the RUC — at that time the police in the north of Ireland — was so sectarian and implicated in the murders of so many innocent Irish Catholics that it later had to be disbanded. Trials were nasty, brutish and short.

After the verdict, my lawyers reassured me that the evidence just wasn’t there and that the conviction would be overturned on appeal. I didn’t believe them. I had no faith in the system. I was going to get out, all right, but I was going to do it my way. I was going to escape. I very nearly succeeded, but was caught just as I was about to get free. Fortunately, my lawyers, at my mother’s urging, persisted, and the case went to the court of appeal where the three judges overturned the conviction and ordered my release. The murder case was reopened in 2011 as part of an overall review of all unsolved Troubles cases.

Niall Murphy is a prominent Belfast solicitor. In 2011 he acted for me, and also for one of the people arrested in Belfast in connection with the new investigation. Niall showed me a transcript of the arrested man’s interrogation. At one point, Niall had intervened forcefully and told the detectives, “You have already dealt with this. Now move on.”

“Now move on.” The three words leapt off the page at me. I loved it.

Still in Berlin, Niall advised me to prepare for arrest on return to London. However, when we arrived back to Stansted there were no police waiting for me. The investigation was already collapsing, although it took several more weeks for it to fizzle out completely. Instead, Georgina, the kids and I came back to ecstatic reviews of Top Boy, which had aired over four consecutive nights while we were in Berlin. Charles Steel called to say Jay Hunt had greenlit a second season.

It was all hands to the pump to get another four scripts written. The murder investigation was fresh in my mind while I was writing, so I had the police pull Dushane in for questioning in relation to the murder of an old rival. At one point, Dushane’s lawyer Rhianna, played by Lorraine Burroughs, tells police they’ve already asked the question. “Now move on,” she says, sternly.

Rhianna’s intervention wasn’t the only thing I brought from real life to season two. Shortly after returning from Berlin, Georgina was diagnosed with stage-four paranasal-sinus cancer. I was in a very dark place when I was writing, and the darkness crept into the scripts. Dushane’s criminal contact Joe, played by David Hayman, is in intensive care, a place I’d unwillingly become very familiar with. Little Michael, the kid played by Xavien Russell, who hero-worships Dushane, is thrown out a window and dies on the pavement at the end of the season while Dushane, hunted by his enemies, is last seen cowering under a bridge on the canal. Like I say, dark. Georgina died shortly after the second season went out.

After two seasons, Channel 4 cancelled the show. Top Boy was dead again.

The story of how Drake, the mega-famous Canadian rapper, stepped in, has been told before. Well-known for his interest in and support for London’s grime artists, he had been introduced to the show by one of his crew while on tour. He loved it, couldn’t understand why it had been cancelled and decided he was going to use his superstar clout to resurrect it. Were it not for him, Top Boy would never have had its Netflix incarnation and gone on to three more glorious seasons. We ended on a high last autumn, with critics in agreement that season five was the strongest yet.

My brain tells me that it was right to finish when we did. It was an incredible ride and it had to come to a stop some time. But my heart tells me something different. And Gerry still tells me stories about what’s going on on the road. I still think about the lives of the characters we — I use the first person plural very deliberately — WE created. The writer/creator, Gerry, the writers in the room, the producers, the directors, and the actors — the “beautiful fuckers”, as David Simon of The Wire calls them, who, after five seasons, became curators of their characters, as tends to happen on all long-running shows.

There have been conversations, some more focused than others, between Cowboy, Netflix and myself about possible spin-offs, about a movie version, a prequel. Perhaps even a musical. I couldn’t help thinking more about Mandy, who in season five developed into an interesting political character for these polarised times, the kind of person who understands what Eugene Debs was all about. Who knows what will happen? At the very least, I hope we’ll see more of Jaq, played by Jasmine Jobson, on screen one day.

But series and movies take time to develop and make. Impatient to continue the deep dive, I decided last year to write a novel (mentioned above), from Jaq’s point of view, exploring the impact on her and those she loves of the power struggle between Dushane and Sully. The novel goes behind the scenes and fills in details we didn’t have time to address in the show. “I’m gonna tell you everything,” Jaq promises the reader.

There still seems so much more to discover about Summerhouse and the characters who inhabit it. ○

“Jaq: A Top Boy Story” by Ronan Bennett is published by Canongate