It was shortly before 2am on 10th September when John Angeli faced the most difficult moment in his career. Sarah Clarke, better known within the halls of the Palace of Westminster as Black Rod, stepped into the House of Commons and called for MPs to decant to the House of Lords. Parliament was being prorogued.

In an underground television production gallery a third of a mile down the road, Angeli sat in a green office chair in front of a bank of around 30 monitors, watching the aftermath. “That was probably some of the most challenging few moments of broadcast coverage because there's no script,” says Angeli, who oversees coverage of both Houses of Parliament as well as the various committees that MPs and Lords sit on. The result is broadcast live on the House of Parliament’s digital streaming video service, parliamentlive.tv, and is picked up by television broadcasters, newspaper websites and other media outlets across the world.

On a drizzly afternoon last November, Angeli was sitting on a red chair in the production gallery for the House of Lords coverage (the broadcast crew's seats match those of the benches of whichever chamber they’re working on). Parliament wasn't in session, which meant nothing was happening on the screens. “There is an order paper for the day and there is an agenda,”he told me. “But there's quite a lot of time when the house is unscripted.”

Prorogation was hard to cover because there was no precedent. Angeli and his director had 10 cameras dotted around the House of Commons chamber (there are five in the House of Lords), many of which can pan and tilt. But in the aftermath of Black Rod's announcement, things go so confused that they didn't know who or what they should be following. “We couldn’t quite tell initially what was happening,” Angeli said, his thin, wire-framed glasses perched on his nose. “We could see that there was some kind of kerfuffle around the speaker’s chair.”

As Black Rod struggled to make herself heard over the din of MPs shouting disapproval, John Bercow was being harangued by members on both sides of the chamber. Some held signs in front of him and tried to pin him in his chair to prevent him leaving – if the speaker couldn't leave the House of Commons, parliament wouldn't be prorogued.

Viewers at home, however, could only see the feed from the external camera, which was broadcasting deceptively calm footage of the Parliamentary Estate. Every other screen on Angeli's feed showed bedlam.

“At that point, ordinarily, what you would be thinking is: ‘Actually do we cut the coverage at this point, because we think there’s some kind of disorder?’” said Angeli. But he was conscious the world was watching and he didn’t want to make the wrong decision.

“If we'd even momentarily gone to the clock shot [which is used in the event of a technical breakdown or an incident in parliament that shouldn’t be televised], there would have been such an extraordinary reaction,” Angeli continued. “So we had to kind of just watch those few seconds and try and decipher what we thought was going on or what might be about to happen. It was uncomfortable for everybody, for the members and for everyone present, and we just stuck with it, and then the speaker started to address the House, unusually from a seated position.”

Bercow made a speech saying that he thought the decision to prorogue was government by fiat. “It was an extraordinary sort of three or four minutes of parliamentary coverage,” says Angeli. “That was that was a tough one, to get that right.”

On 21st November 1989, proceedings from the Commons were televised for the first time. Viewers at home were treated to a speech by Conservative MP Ian Gow, in response to the State Opening of Parliament. It was “quite stilted,” says Nick Anstead, associate professor in politics at the London School of Economics. “They had quite strict rules in terms of what they could actually show.”

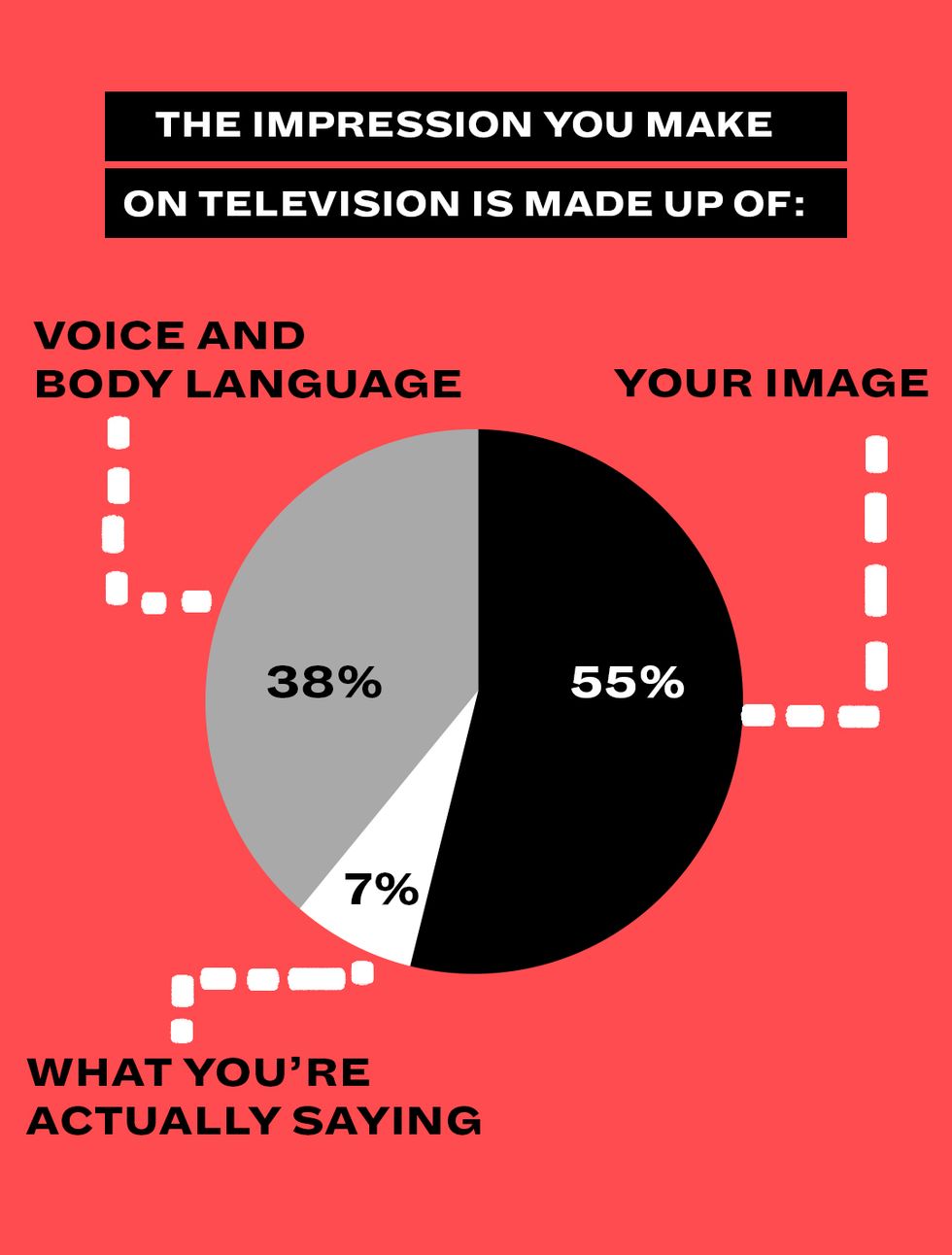

“I have always voted against the televising of the proceedings of this house,” Gow told the Commons, to cheers. “And I expect that I always will. Despite the strongly held opinions which I have on these matters, I received a letter three weeks ago… which made the following preposterous assertion: ‘The impression you make on television depends mainly on your image: 55 per cent, with your voice and body language accounting for 38 per cent of your impact. Only seven per cent depends on what you are actually saying.’”

Gow was summarising a fear many MPs of the time held of the advent of television. Timothy Kirkhope, now Lord Kirkhope, a Conservative colleague of Gow’s, was another MP who opposed televising proceedings – despite the fact that he’s a keen amateur filmmaker. “I thought it would lead to behavioural changes which would distract from the debates,” he says. “It would have made people behave in a way which they wouldn’t normally have behaved in, in debates of the important subjects we were discussing. So I initially opposed it.”

“There's been less research about the broadcast of parliamentary debates than about the televised individual leadership debates,” explains Delia Dumitrescu, a lecturer in media and cultural politics at the University of East Anglia, “but it is safe to say that the effect is the same, namely: televising the debates leads to a greater emphasis on individual politicians, on who they are, how they speak and how they present themselves.

“It leads to a greater personalisation of parliamentary politics than before, with an increased emphasis on how an argument is presented, and on who presents it - at the expense of the substance of the argument itself.”

A Commons vote, held in February 1988 to decide whether to hold an experiment in broadcasting proceedings, was passed only by a margin of 318 to 264.

The arguments made in favour of introducing cameras into the chamber were simple: shining a light on parliamentary proceedings in real time allowed the public to feel better informed about how their MPs were representing them than by delayed reports cherry picked by reporters for newspapers or radio the following day. For television broadcasters, who had been knocking on the door of parliament since they first started producing news programmes, it allowed them to fill schedules, and to better cover the back and forth of debate.

Opponents – including Kirkhope – worried that people would play up to the cameras, and the tenor of debate would weaken. “You know, there are still some members who think it’s a bad idea to have allowed the cameras in,” says Angeli. “But the intention of both houses now, despite a small number who may be against the idea of televising, is the cameras and the live streaming afford transparency – and that that's what we want to offer.”

That transparency has changed by degrees over the 30 years that parliamentary proceedings have been held in front of the cameras, rather than in camera. At first, strict rules defined by MPs on the select committee on televising of proceedings meant that the camera could only point at whoever was talking at the time – and had to try and keep only that member in shot as much as possible.

Reaction shots, which could capture the faces of MPs who were being referred to by colleagues, were strictly banned – which caused consternation amongst broadcasters who wanted to inject some drama into parliament. “Within about a year or so of televising, it became obvious that you weren't getting a sense of the chamber,” says Angeli. It took two months for the select committee to cave on allowing reaction shots – though initially only during regular debates, and not during question time or ministerial statements. More recently, Angeli’s department has introduced two new eye-level cameras into the Commons chamber, allowing them to pick a dramatic shot of the tellers looking straight up at the speaker when announcing the results of the votes. (The MPs themselves liked the addition of the new cameras, and have asked Angeli’s team to add another two cameras at the other end of the chamber.)

The power to pick and choose what to cover has also been taken out of the hands of news broadcasters. Angeli – who used to run quarter-inch tapes of audio recordings of debates up and down the stairs of 4 Millbank, next door to where he currently works for parliament – calls the initial coverage “partial coverage of what the media would not unreasonably regard as the interesting things”, such as Prime Minister’s Questions, the Budget, the State Opening of Parliament, and urgent questions or controversial bills. It has since evolved – thanks to the development of online streaming, rolling coverage through broadcast TV channel BBC Parliament, and social media, to be a viewer-led experience. Log on to Parliamentlive.tv and it’s possible to pick and choose from the 35 to 40 events happening across the parliamentary estate on any given day – whether that’s the key debates in the House of Commons or Lords, or a tiny committee at Portcullis House. “Everything gets filmed and streamed live,” says Angeli, who oversees 70 to 80 hours of live streaming coverage on parliament’s busiest days – the equivalent of three rolling news channels.

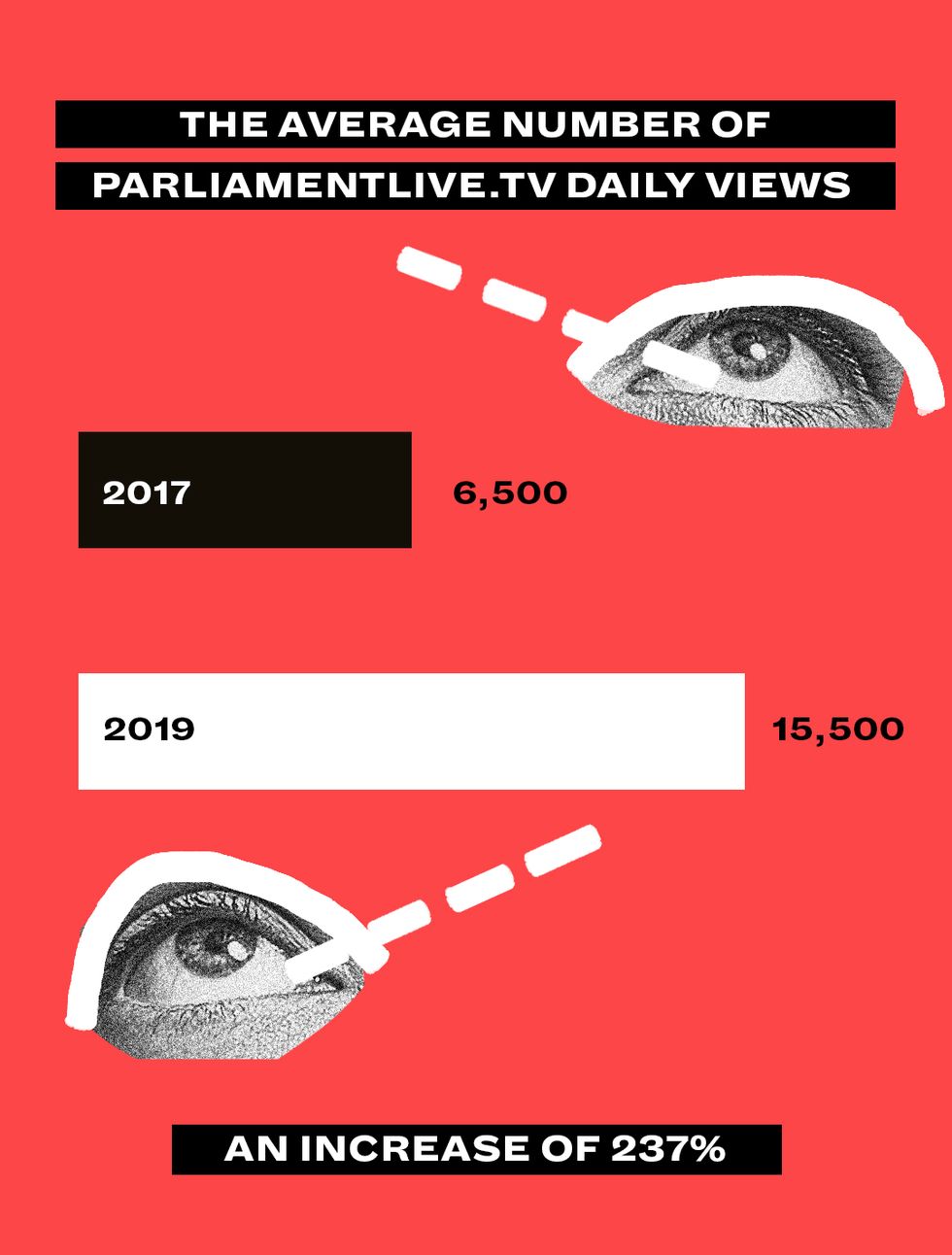

Though many people tune in to BBC Parliament, which has experienced record viewing figures of 1.5 million people on 3rd September and 2.6 million during that entire week, which marked Boris Johnson’s first defeat as prime minister, people are not just waiting for traditional television to watch parliamentary proceedings. The average number of daily views to Parliamentlive.tv has increased 237 percent, from just over 6,500 each day in 2017 to more than 15,500 in 2019. Only six in 10 viewers are from the UK, demonstrating there’s an increasing appetite to see what’s happening in the UK parliament from outside the country.

“We've been very aware over the past 12 months that this is a different order of public engagement to anything that we've seen in the last 30 years,” says Angeli, who admits that the pressure on his team has increased to ensure the coverage of debates matches the increased scrutiny.

The Brexit process has also been taxing on the equipment. Angeli joined parliament in 2011 from BBC News Online with a mission to modernise. In 2014, he oversaw an 18-month long update that overhauled the way the systems worked, and took some of the core service offsite from parliament – which wasn’t equipped to deal with the vast racks of servers required to deliver an internet-based streaming video service.

But the system Angeli had helped instigate was designed for a pre-Brexit world – and pre-Brexit levels of public scrutiny of parliamentarians. “That was a completely different order of audience from the one that we built for,” he says. “We hadn’t reckoned on hundreds of thousands of people watching.” When more than 2.5 million people watched some sort of coverage of Parliamentlive.tv between January and April 2019 – as the meaningful votes were debated in parliament – the amount of traffic coming to the site required a rapid refiguring of the system’s capabilities. “We had a really difficult few days on some of the big votes, where things just juddered to a halt because the amount of audience there was too much for the service to cope with."

Coverage of what goes on in parliament is still more tightly controlled than you may expect, which is unlikely to change in the social media age. The broadcasters have approached Angeli and MPs asking to install high-definition 360-degree cameras into the chamber from which they can pick and choose shots of the chamber to broadcast – taking the power out of Angeli and his colleague’s hands. So far they’ve refused. Instead, parliament’s own in-house broadcasting unit has the final say on shot selection, and that edit is provided to television channels pick from.

“The intention is to offer people coverage of what’s being said,” says Angeli. “Whereas actually what might be tempting to show is other things that aren’t being said but are interesting nevertheless. That could be quite distracting and confusing if it was used in an unhelpful way.”

As partisan social media sharing of images from parliament increases – such as Jacob Rees-Mogg lying recumbent on the front benches – the willingness for parliamentary authorities to open up all the cameras to everyone diminishes. Angeli fields few complaints from MPs because the rulebook he and his team has to follow lays out very strict guidance that helps keep coverage impartial, but the few knocks at his underground office at 7 Millbank generally come from MPs quibbling over a piece of footage they’ve encountered on social media that has been recut or zoomed into a specific place to capture an MP’s moment of embarrassment. “We've had to help them to understand what's happening, which is that cutting and pasting video is as easy as cutting and pasting text now,” he says.

Still, he can understand their frustration. “This is MPs' place of work,” he says. “If they feel they're constantly under scrutiny from several camera angles, it makes it quite a difficult environment to then think of as your workplace. In the same way, if I took cameras into 4 Milbank next door [where the BBC, ITV and Sky News have their Westminster bases], it would change their approach to work.”

In the last 30 years MPs have grown accustomed to the idea that the cameras are there in the Commons, but they know that the team broadcasting the coverage are largely respectful of the fact it’s their office. “It would be more challenging to say: ‘Let's open up all the camera angles and let everybody do what they want with them’, because we actually see what people do with that sort of stuff online."

Viewership of parliamentary proceedings has increased enormously, driven by the centrality of Brexit to everything happening in the country at present, but with increased scrutiny, MPs have also undergone a change. “What was interesting was the complete change in the appearance of people,” says Kirkhope, who sat in parliament for 10 years from 1987 to 1997, as cameras were introduced to capture proceedings. “Some of it was just small stuff: green folded handkerchiefs appearing in top pockets that weren’t there before,” he says. “One guy was accused by his colleagues of wearing mascara.” And the temperature rose in the chamber – literally. “They hadn’t quite perfected either the camera or the lighting. People who perhaps normally didn’t sweat started to. Their brows were perspiring because of the heat of the television lights.”

Television cameras entering the chamber also ushered in the era of the soundbite. “If you read some of the old speeches, they are incredible,” says Kirkhope. “They're wonderful speeches, but they need to be looked at as a whole speech. Once you have TV, the idea was you had to try and get a line that could be remembered and was used by the people who edited the programmes and the TV coverage.”

Some MPs could adapt to the new era, but others simply fell by the wayside as more polished TV performers swept in. Kirkhope’s predecessor as MP for Leeds North East was Keith Joseph, who had represented the constituency since a 1956 by-election. Joseph would have been ill-suited for the televised era of parliament, says Kirkhope, because he would drive himself to nervous vomiting before television interviews. “Having TV in the house produced different kinds of people standing for parliament,” he says. That’s fed through to the selection of candidates by parties: a conscientious would-be constituency MP may end up being shunned in favour of a telegenic public speaker with a knack for coining a catchy phrase.

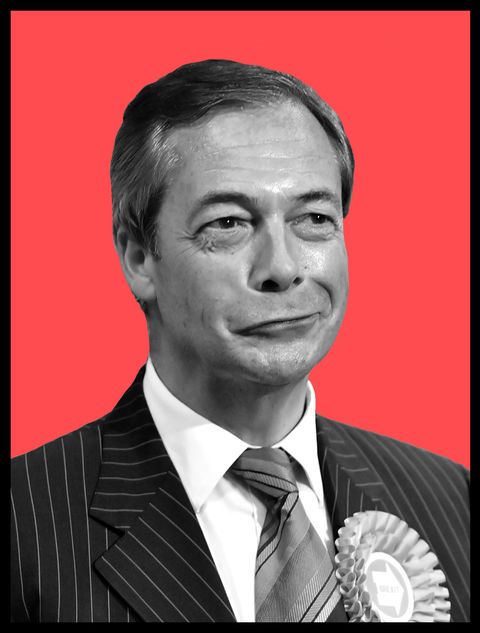

The social media revolution is having its own effect. “One of the interesting things about Jeremy Corbyn is that he’s not by many measures a good Commons performer,” says the LSE’s Anstead. “He’s not a good debater. But what he does do often is ask a question that will get traction with his supporter base on social media, they’ll extract the clip, and it’ll go viral. It’s a similar tactic to one used by Nigel Farage in the European parliament.”

Indeed, some worry that debate has been lost from parliament entirely, with the green benches instead becoming a backdrop for people to make pronouncements with the veneer of respectability. “This isn’t an entirely new idea; for a long time parliamentarians would ask a question about some important issue in their constituency, then they’d put it out on an election leaflet, saying I asked a question about it in the house,” says Anstead. “It’s a version of this, but it’s hyper-intensified.”

As the Brexit process has shown, putting public debate in front of the cameras can also have unintended consequences, producing more heat than light. Politicians looking to climb the greasy pole are potentially more likely to pick fights with colleagues to score points – and that behaviour is incentivised by the tribal nature of social media, and the competitive nature of television. “To attract a larger audience, it's also likely to lead to a more conflict-focused reporting of the debate,” says Dumitrescu. “That can lead to a coverage that emphasises more the areas of difference, rather than the areas of consensus.”

Kirkhope has come round to the benefits of broadcasting parliamentary coverage, recognising that it allows for more direct accountability and makes it easier for ordinary people to take an interest in how well their MPs are representing their interests. Nonetheless, he’s continued a campaign that he first raised back in the late Eighties with a letter to Peter Plouviez, general secretary of Equity, the actor’s union. “I wrote a letter to him when TV arrived applying to join. ‘Now that I am going to be an actor, I don't see why I shouldn't be a member of your union.’ The letter I got back was quite funny really as well. He just said, ‘But you haven't yet got the experience. When you have more experience on this, please apply again.’ Ever since, on reasonable interludes, I have tried to get into Equity.”

Thirty years on, it’s impossible to imagine going back to a point without cameras in the Commons chamber. But as some of the most extreme examples of grandstanding on both sides of the Brexit debate have roiled parliament to boiling point on multiple occasions in the last few years, it’s worth asking: were the naysayers right? Does putting cameras in the proceedings provide a warped view of what parliament is like?

“We’re certainly seeing over the past year that a lot of the coverage will be about highly contentious issues, when there's been quite a lot of ill-tempered debates around things like Brexit, and the public only ever get to see those moments,” says Angeli. “And that that's not actually what parliament is generally like.

“You keep putting those video clips out there, and you just build up an image in the public mind that when parliament is sitting, the chamber is constantly full, and members are shouting at each other. And that's probably true around one or two per cent of the week,” he says. ”What they're not seeing is all the good work that's being done pushing bills through, going into committee and doing the scrutiny.”

Those are issues that some MPs raised in the chamber when televising coverage was first debated in the Sixties, Seventies and Eighties. “Some members could see that aspect of it and thought that actually, in the long run this is going to be corrosive, not a good outcome,” says Angeli.

“I don’t buy that in its entirety,” he adds, “but I do see that there are some risks in transparency. There always are. But at the same time, there are so many plus points about it that I think it has been difficult at times, but I'm not sure that it would have been tenable, in our modern communication era, for parliament to continue to be behind closed doors.”

As his team plans to move out of 7 Millbank in the next few months to a new site in Canon Row, under the shadow of Big Ben’s tower, the technological advancements will improve. Angeli wants to make the vast amount of footage more accessible – for both media and the general public – by live transcribing the text and allowing people to search through it to find the relevant, timestamped clip they want. A member of the team has already developed, in their spare time, a computer program that can look at an MP appearing on screen and identify who it is that is speaking – a quicker way of discerning the 650 MPs and 793 Lords than the thick, A6-sized stapled booklets of members’ names, faces and political parties that the directorial team use at present.

“The speed with which news is now pushed out there has to be matched by parliament,” says Angeli. “It’s not going to be good enough to produce a committee that's three hours long and just post the video. If it's not described and searchable, and you can't find the keywords within it and find that the quote, then it's limited of limited value.”

It’s not just the behind-the-scenes team that will be moving locations in the near future. Parliament itself will be decamping: the Commons to Richmond House, and the Lords to the Queen Elizabeth II Centre. That will provide opportunities for Angeli’s team to make the coverage more direct.

One major brickbat laid against current coverage of both houses is that the cameras are – by necessity – placed high above members, looking down on them and making them seem remote. With the exception of a rare 1968 ITN television trial, which placed cameras on the benches of the House of Lords, shunting peers from their seats, parliamentary real estate is so tight that cameras couldn’t be placed anywhere but above MPs’ heads. But placing the two cameras at eye-level changed perceptions. “Somebody in my team said it feels like you’re being welcomed in and you’re meant to be there,” he says. During my visit, Angeli and his team seem fixated on the 1968 ITN trial. “It just offers a very different feel to the top-down shots that we have, so it's something that we're currently thinking about both for the for the coverage of the next five years before we decamp, but also for Richmond House and Queen Elizabeth II."

One thing’s for sure: the eye-level coverage won’t be provided by cricket stump-like cameras, which Angeli’s team tried placing on the table from where David Cameron and Ed Miliband exchanged volleys over the dispatch box back in the mid-2010s. “It looked dreadful and was very goldfishy."

While Agneli admits change can be a long time coming, “the ambition is definitely there.” Unlike the run-up to the launch of parliamentary broadcasts in the Eighties, when the major sticking point was intransigent representatives, the challenge now is a different one. “This isn't trivial when you're looking at 30 locations, all essentially broadcasting and managing live content across and sprawling estate, part of which is got a World Heritage status,” he says. “You can't just bang a camera up somewhere without having to go through a lot of processes.”

How revolutionary the next 30 years of parliamentary coverage will be could in large part depend on what happened on 12 December last year. Parliament has always been one of the three key pillars of the British constitution, but in recent years has flexed its muscles more than before – meaning more eyeballs have been on every twist and turn of its proceedings.

One member of the administration committee, which now helps guide the coverage of parliamentary proceedings, explained to Angeli that’s it’s impossible to put the genie back in the bottle. And while the fire and bluster may abate if Brexit unfolds smoothly, parliament is only likely to become more open. “I’m not sure we’re going to see similar numbers in [2020] around things like Brexit,” says Angeli. “But where I’d like to see numbers going up is around the stuff that doesn’t always make the national news.”

While the adrenaline pumped through his veins on that extraordinary night back in September, the prorogation that never happened, Angeli is a local news man at heart. Perched in the Lords’ broadcast gallery, he reminisces about his days as a parliamentary reporter translating what happened in this small square of central London to local radio audiences in the West Midlands, Stoke, Manchester or Leeds. “I would tell people about what their local member or members had said about the closure of the factory or the loss of jobs; what was happening to the hospital or the school,” he says. But he’s aware those days are gone, and budgets have been cut so much that local coverage of parliament is almost non-existent. “I think we have a duty to describe what’s going on in parliament much more smartly, to continue that process of posting material and alerting material and alerting individuals, and making up that gap that didn’t use to exist.”

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox